The federal government, by taking Americans’ property through civil forfeiture, raked in more money last year than burglars did.

According to crime data from the FBI, and highlighted by the blog Armstrong Economics, federal law enforcement agencies took in more money through the proceeds of cash, property, and houses seized through civil forfeiture in 2014 than burglars did.

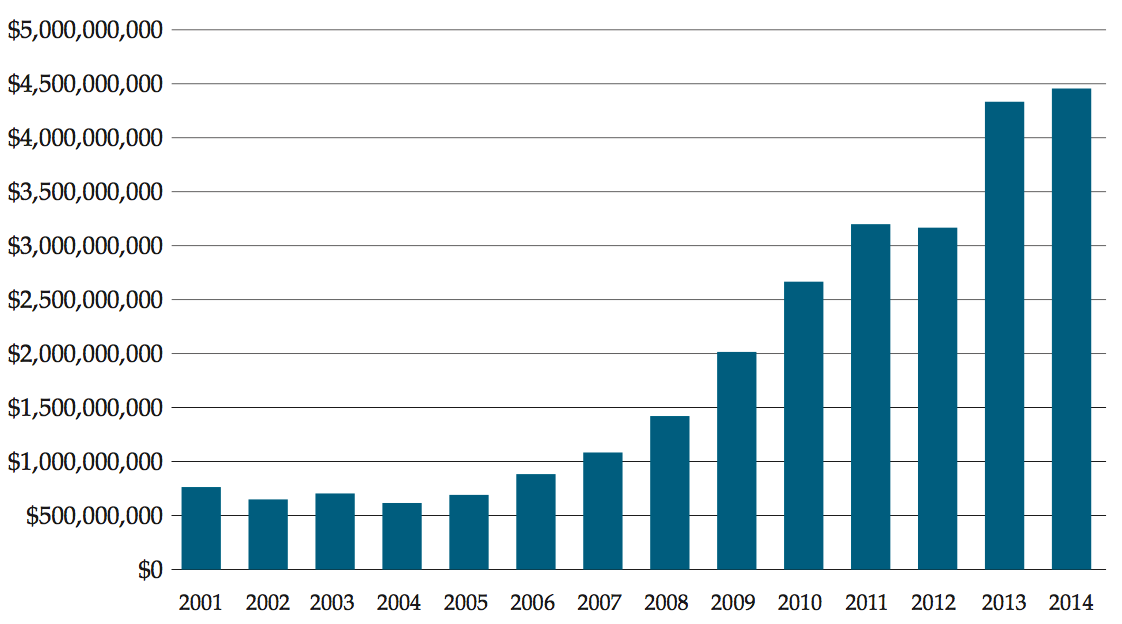

A report from the Institute for Justice found that last year, the Justice and Treasury Departments reported net assets—money left over after expenditures—of $4.5 billion in the agencies’ asset forfeiture funds. The Departments of Justice and Treasury deposited more than $5 billion total into their accounts in 2014.

Net Assets in the Justice Department and Treasury Department’s Forfeiture Funds (Chart: Institute for Justice)

The FBI, meanwhile, reported that burglary victims lost roughly $3.9 billion in property last year.

2014 marks the first year the amount forfeited by the federal government under civil forfeiture laws outpaced the value of property stolen by burglars.

“Thirty years ago, the value of forfeiture property was measured in tens of millions annually,” Jason Snead, a policy analyst at The Heritage Foundation, told The Daily Signal. “Today, it is consistently measures in the billions and is still growing.There is no doubt that many law enforcement agencies are using civil asset forfeiture as a revenue-generating tool to supplement their budgets.”

Civil forfeiture is a tool that gives federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies the power to seize property—including cash, cars, and houses—if they suspect it’s connected to criminal activity. In recent years, the practice has come under scrutiny, as law enforcement has been found using civil forfeiture to pad budgets—without the oversight of city councils or state legislatures—and seizing property without charging victims with crimes.

In many states, law enforcement agencies can keep 100 percent of the proceeds from the property they forfeit, and their ability to do so creates what many opponents of forfeiture say is a perverse profit incentive for law enforcement to seize property under civil forfeiture.

“There are a number of reasons this is troubling—not only because sizable portions of agency budgets are now derived from the forcible seizure of property, but because details of how these funds are spent escape public scrutiny,” Snead said. “Agencies can use forfeiture to self-finance, and that seriously undermines accountability, transparency, and trust in law enforcement officers.”

In a statement to The Daily Signal, a spokesman with the Justice Department defended the government’s use of civil forfeiture.

“Appropriate use of asset forfeiture law allows the Justice Department to safeguard the integrity, security, and stability of our nation’s financial system and provides unique means to go after criminal and terrorist organizations, while protecting the civil liberties of all Americans,” the spokesman said. “As we continue our comprehensive review of the asset forfeiture program, we will stay focused on deterring criminal activity, returning the proceeds of crime to victims, and defending the rights of our citizens.”

Despite criticisms of federal and state governments’ use of civil forfeiture, comparisons of net assets in the federal government’s asset forfeiture funds to the amount lost in burglaries are not perfect.

According to the Washington Post and FBI crime reports, the total amount stolen last year through burglaries, thefts, and motor vehicle thefts is $12.3 billion.

>>> Why These Women Think the Government Seizing One Home Benefited Their Neighborhood

Additionally, as the Institute for Justice noted in its report, net assets in the Justice and Treasury Departments’ asset forfeiture funds provide a better look at how often law enforcement agencies are using civil forfeiture in recent years as opposed to net deposits. The funds’ net assets, though, do include cash, cars, and houses forfeited over several years.

The FBI, by comparison, looks at a single calendar year.

Though both federal agencies deposited more than a combined $5 billion into their respective asset forfeiture funds, a spokesman with the Justice Department noted that deposits in 2014 included $1.7 billion related to Bernie Madoff’s case and $1.2 billion related to the Toyota Motor Corporation case.

Additionally, net assets into the asset forfeiture funds operated by the Department of Treasury and Department of Justice do not include the proceeds of cash, cars, and houses forfeited by state and local law enforcement agencies.

Not all states require agencies to report their forfeiture proceeds, but the Institute for Justice found that in 2013, law enforcement agencies in 14 states raked in $250 million from civil forfeiture.

Snead noted that though there have been many instances of law enforcement abusing civil forfeiture, the government does use the practice to legitimately deprive criminals of their ill-gotten gains.

“[C]omparing the value of seized property to the value of property lost to burglary can give the impression that all, or even most, forfeitures are cases of government-sponsored theft. I don’t think this is accurate,” he said. “We have noted a disturbing number of instances of abusive forfeitures and systemic deficiencies in how forfeiture is practiced today, but in all likelihood the majority of forfeiture cases do target the proceeds of crime. We need sweeping forfeiture reform, but we should be careful not to paint with too broad a brush.”