PHILADELPHIA—On a September day in 2014, Leandro Banks saw his money disappear in an instant.

Banks, an independent contractor, left the bank with $1,858 in his pocket. The money came from his paycheck of nearly $5,000, Banks says.

Some of it he deposited, some he shared with an employee, and the rest—the $1,858—he says he intended to keep at home.

But in between the bank and his house, Banks stopped on the street to talk with some friends. Police said they saw him make a “transaction” by passing marijuana to another man in exchange for cash.

>>> First in a three-part series on civil asset forfeiture in Philadelphia. Read part two and part three.

In an interview with The Daily Signal more than a year later, Banks, 46, says he simply was exchanging a handshake.

When officers with the Philadelphia Police Department approached Banks, though, he took off running.

They caught him three blocks away and said they found two ounces of marijuana and nearly $2,000 in a pocket of his blue shorts.

The officers seized the cash under Pennsylvania’s civil asset forfeiture laws, believing that it was connected to the marijuana. Banks contended that the money came from his paycheck.

“I was upset,” Banks recalls. “Even though it was a year ago, that’s my money. I worked hard for that. I said, ‘I got to fight it.’”

“That’s my money. I worked hard for that. I said, ‘I got to fight it.’”—Leandro Banks

So Banks began his foray into Philadelphia’s civil asset forfeiture machine, beginning in a small, rectangular room in City Hall called Courtroom 478.

There, the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office attempted to settle with Banks, first offering him $1,500 and then lowering its bid to $500. The contractor says he declined.

Banks told the city he would be happy to go to court to show the cash came from honest work. And he had the pay stub to prove it.

Inside Courtroom 478

Civil asset forfeiture is a tool that gives law enforcement the power to seize property and money suspected of being related to a crime. Originally, it was a way for police to target drug trafficking and money laundering.

Law enforcement officials in Philadelphia contend today that asset forfeiture is vital for eliminating the profit incentive for those in the drug trade.

Over the past few years, though, law enforcement agencies across the nation have faced growing criticism for what is seen as their abuse of forfeiture. Philadelphia, in particular, is the target of substantial backlash.

For citizens such as Banks whose cash, houses, or motor vehicles are seized by police in Philadelphia, the journey to get their property back begins in Courtroom 478, located halfway down a long hallway.

On a Thursday morning in July, the dimly lit hallway is nearly empty. A man passes by, his footsteps echoing, and he ducks into another courtroom further along.

Every so often, one of the city’s assistant district attorneys walks through the doorway of Courtroom 478 and into the hall, followed by a confused-looking property owner gripping paperwork.

The prosecutors sometimes converse with the property owners in hushed tones, discussing the details of proposed settlements or instructing them on what additional forms they need to fill out.

Inside the courtroom, wooden chairs are arranged in rows along the back wall. On this day, half the seats are filled. The occupants sit with their arms tightly crossed against their chests.

Courtroom 478 typically is busy on Wednesdays, when people whose vehicles were seized are summoned to appear.

Fridays, by contrast, are much slower. That’s when people who had less than $50 seized by law enforcement get their day in Courtroom 478.

For many of those property owners, fighting for the return of under $50 isn’t worth the hassle of spending a morning—and possibly several more—in Courtroom 478. On a Friday in July, only one person is listed on the docket, and that person doesn’t show up.

Darpana Sheth, a lawyer with the Institute for Justice who is leading a class action lawsuit against Philadelphia, says her group has seen forfeiture petitions for as little as $7 or $9. Going to Courtroom 478 to fight for such a low amount may seem futile, she says, but it’s those small sums that boost the city’s forfeiture revenue.

“If that’s what’s been taken from you, it’s a rational, economic decision that it’s not worth your time to go fight over that,” Sheth says in an interview with The Daily Signal. “But it’s important to know that it’s through this kind of accumulation of small-dollar amounts that most of Philadelphia’s slush fund of forfeiture revenue has been accumulated.”

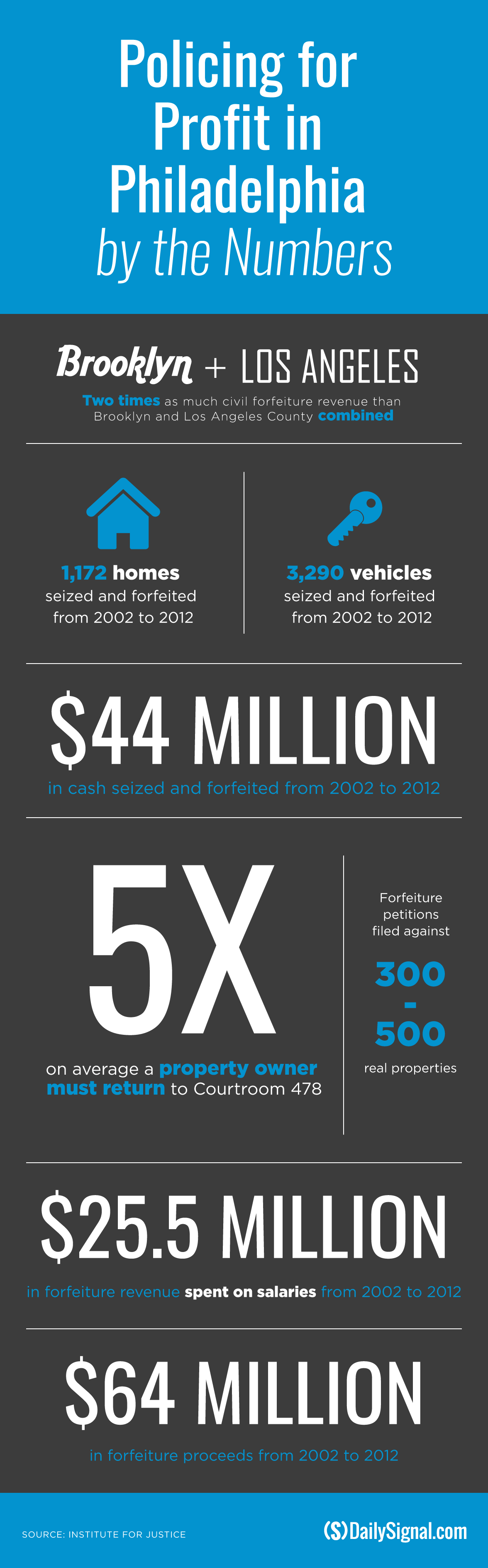

Of the nearly $6 million—an average—forfeited annually by action of the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office from 2002 to 2012, $4.5 million came from cash seizures, according to an analysis conducted by the Institute for Justice.

The American Civil Liberties Union found in its own investigation that half of cash forfeitures in Philadelphia between 2011 and 2013 involved amounts of less than $192. Just 10 percent were more than $1,000. The ACLU examined a random sample of 351 cash forfeitures over that three-year span.

In the weeks following The Daily Signal’s visit, the district attorney’s Public Nuisance Task Force—which oversees the process—decided to prohibit forfeitures of less than $50. Also ended were forfeitures tied to low-level misdemeanors.

Waiting to Meet a Prosecutor

For those summoned to Courtroom 478 on this Thursday, waiting to meet with an assistant district attorney is an hours-long affair.

The prosecutors often meet directly with property owners and help guide them through the process. Such involvement has earned the criticism of Sheth and other forfeiture opponents, who argue that the lack of a neutral party violates due process.

David Earley had $150 in cash and three cell phones seized in June, when police arrested him for possession of cocaine, he tells The Daily Signal. The case was dropped and the charges dismissed.

Earley, 36, says he doesn’t care about the cash—it’s one of the cell phones he wanted back. He waited for nearly two hours to learn if it would be returned. (It was.)

Another property owner, a woman named Rochelle, says Officer Jeffrey Walker seized $7,000 from her in 2012. The next year, the narcotics officer was arrested and charged with planting drugs in and robbing a suspect’s house. In July, Walker was convicted and sentenced to three and a half years behind bars.

On this Thursday in July, Rochelle appears with hopes her money will be returned, but she learns that it will be another 10 to 12 weeks before she sees the cash—another 10 to 12 weeks in what has been a three-year battle with the city.

Back in Courtroom 478, a broken clock leans up against the wall.

Guilty Until Proven Innocent

There are 16 seats on the left side of Courtroom 478, seats meant to hold a jury. But they’re empty.

A man sits at the front of the rectangular room. In any other courtroom, a judge would sit there. In Courtroom 478, though, the man isn’t a judge. He is a scheduler who tells property owners when they need to appear next.

Residents such as Earley and Banks, whose cash or other property was seized by the Philadelphia Police Department, receive a notice of forfeiture. They are required to appear here to prove they were unaware of any illegal activity involving their property.

This notion—of being guilty before proven innocent—is one of the many points of contention for critics of the city’s forfeiture system.

Sheth says it denies the presumption of innocence.

“The presumption of innocence is being turned on its head.”—Darpana Sheth

“The property owner bears the burden to affirmatively prove that they didn’t know about the illegal activity or they didn’t consent to it,” Sheth tells The Daily Signal, adding:

That’s where you get the reversal of the presumption of innocence. In these civil forfeiture cases, the property owner has to come forward and affirmatively prove a negative, that they didn’t know about the illegal activity, which is a very hard thing to do. The presumption of innocence is being turned on its head.

Sheth and the Institute for Justice have homed in on specific aspects of the system that threaten property rights, including the profit incentive created by forfeiture.

‘Direct Financial Incentive’

Philadelphia took in $64 million in forfeiture proceeds from 2002 to 2012, according to the Institute for Justice. Approximately $25 million of it went to paying law enforcement salaries, including those of lawyers working for the city in Courtroom 478.

A report from the Pennsylvania Attorney General’s Office found that Philadelphia law enforcement seized $3.4 million from 2013 to 2014 through civil forfeiture.

The ACLU reported that the district attorney’s office received nearly $2.2 million from forfeiture proceeds in 2012, which equals 7.3 percent of the agency’s budget.

“Those prosecutors have a direct financial incentive in the outcome of that proceeding. If property is eventually forfeited, that goes directly to the district attorney’s office, which uses it to pay salaries, including the salaries of these prosecutors,” Sheth says. “They have a direct financial interest that is very problematic.”

Prosecutors for the city don’t see it that way.

In an interview with The Daily Signal, Andrew Jenemann, chief of the district attorney’s Public Nuisance Task Force, says forfeiture proceeds are split between the police force and the district attorney’s office. The agencies use the money for different purposes, Jenemann says, and his task force has no say in it.

The money represents a small percentage of the budget, he says:

Some of the criticism is that we’re taking random people’s money, and that can’t be further from the truth. I don’t know if you’ve ever had the experience of living next door to a drug house or next door to a place that’s selling drugs. Ultimately, what this is all about it disrupting the drug trade and taking away instruments of crime that [criminals] use to further it.

Return Engagements

But the profit incentive isn’t the only reason opponents say the process is unconstitutional.

“Some of the criticism is that we’re taking random people’s money, and that can’t be further from the truth.”—Assistant District Attorney Andrew Jenemann

Property owners aren’t granted a right to counsel and often are asked to fill out complex forms filled with legal jargon.

Additionally, after appearing in Courtroom 478 for the first time, many property owners are required to return four, five, or even six times before learning whether their cash, vehicles, or houses are forfeited for good or will be returned.

Earley was lucky; he appeared in Courtroom 478 just once. Rochelle, who didn’t wish to share her last name, was there three times. Banks appeared six times, records show.

Failing to appear even once leads to automatic forfeiture of cash and automobiles, critics complain.

In January 2014, Philadelphia police seized $580 and a Buick LeSabre from Nassir Geiger, a lifelong city resident. Geiger, who joined the Institute for Justice’s class action lawsuit, appeared in Courtroom 478 several times to fight for his car and money.

Geiger, a sanitation worker employed by the city, wasn’t aware that the district attorney’s office had filed separate forfeiture petitions for his car and about $465 in cash.

According to court documents, Geiger never received a hearing notice about his cash and failed to appear in Courtroom 478 as scheduled on March 11, 2014, and June 16, 2014.

Because he didn’t show, his money was forfeited.

‘Bad Information’

Contrary to their critics, prosecutors disagree that missing a hearing leads to automatic forfeiture.

Jenemann, an assistant district attorney, says prosecutors do research before acting to forfeit real property—a house, business or warehouse—if a person fails to appear. He says they comb real estate tax records and other public documents, and look for addresses listed on a property’s water bills.

If a property owner cooperates and participates in the process, and then fails to appear in Courtroom 478, Jenemann says, prosecutors aren’t afraid to reopen cases involving property that had been defaulted.

Also, if property is forfeited after the owner fails to appear, Jenemann stresses, he or she can request that the court reopen a case by filing a motion to vacate the previous forfeiture. In some cases, the Pennsylvania courts reopen forfeiture cases involving houses, cars, and money.

“There’s a certain amount of bad information that’s been put out there,” Jenemann says. “There’s a certain amount of unfairness in the way [forfeiture] has been portrayed. We’re always trying to improve the process. You want to get from what it is to where it should be.”

Jenemann notes that the number of times claimants have to appear in forfeiture court is based largely on the defendant and whether he or she has an open criminal case.

Under Philadelphia’s court rules, he says, status hearings must be conducted every few months until a criminal case is closed. That can keep property owners such as Banks coming back to Courtroom 478 five or six times.

Property owners in Philadelphia fighting for their cash, cars and houses sometimes must appear in Courtroom 478 up to 10 times.

The drawn out nature of forfeiture cases, criticized by opponents of Philadelphia’s practice, is one aspect of the program Jenemann has changed.

“We are responding to the criticism by evaluating past policies and past procedures, and where we find them to need updating or changes, we’re making updates or changes,” he says. “But I don’t think the criticism has been fair.”

‘Every Last Penny’

Banks’ case underscores the concerns of those fighting the system. The contractor represents thousands of property owners whose cash, cars, or residences were seized even though the property wasn’t tied conclusively to illegal activity.

Banks was found guilty of possession of marijuana with intent to manufacture or deliver, according to filings with the Municipal Court of Philadelphia County. His pay stub, however, showed that the $1,858 seized by police wasn’t tied to the drugs.

He was sentenced to 18 months’ probation.

Banks and the district attorney’s office reached a settlement in August, court documents show. As a result, Banks says, he received “every last penny back.” He also was asked to sign a waiver saying he wouldn’t sue the city.

Such waiver requests aren’t uncommon, as evident in the 2012 case of George Reby, who had $22,000 in cash seized in Tennessee. Reby, who got his money back, was asked to sign a waiver saying he wouldn’t sue the state.

In the interview with The Daily Signal, Banks says he didn’t understand why police went after him and not the man who they believed was selling marijuana, especially when law enforcement is focused on taking drugs off the streets.

And although Banks was able to prove that his money wasn’t tied to illegal activity, effectively beating Philadelphia’s forfeiture system, he laments that others won’t find it that simple.

“For someone who doesn’t have a pay stub, it wouldn’t be so easy,” Banks says, adding of his money: “I needed that change.”