The deal struck by Democratic Sens. Chuck Schumer of New York and Joe Manchin of West Virginia on the so-called Inflation Reduction Act would extend what was sold as a temporary expansion of Obamacare subsidies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The extension would be for three years, at a cost of $64 billion.

Democrats claim that without the extra subsidies, premiums for 2023 will soar and millions of people will lose coverage. They further claim that Congress needs to act now, before insurers finalize their 2023 premiums.

Those claims are all wrong and misleading.

Extending the enhanced subsidies will have next to no effect on the premiums charged by insurers. Furthermore, not extending the extra subsidies means that Obamacare enrollees will simply go back to paying in 2023 what they did in 2020.

Understanding why that is the case requires taking a closer look at three things: projected premiums for 2023; how Obamacare’s subsidy design works; and the effects of the subsidy-enhancement provision.

So far, 20 state insurance departments have publicly posted their insurers’ proposed 2023 rates for Obamacare plans. As is typical in most years, the proposed rates vary considerably by state and insurer.

For instance, half of California’s 12 Obamacare insurers proposed rate increases in the low single digits, while all but one of New York’s 12 Obamacare insurers proposed rate increases of more than 10%. Overall, while about one-quarter of insurers are asking for double-digit increases, at the other end of the spectrum some insurers are proposing to reduce their rates by 1% to 3%.

Collectively, the currently available rate filings indicate that when final rates for all insurers are posted in October, the national average increase in premiums for 2023 will likely be about 8%.

As always, the biggest factor affecting health insurance premiums are claims costs, which are driven by changes in the price and volume of medical services. Insurer rate filings show that, for 2023, they expect their claims costs to increase by between 4% and 8%, which is roughly in line with pre-COVID-19 trends.

The past couple of years saw a moderation in health spending as the additional medical costs associated with the COVID-19 pandemic were offset by reductions in the volume of other care. In 2022, volume has grown again as enrollees sought medical care that they had deferred during lockdowns, with some insurers expecting that rebound to continue into 2023.

Interestingly, some insurers included in their filings projections for how ending versus continuing the enhanced subsidies would alter their proposed rates, with most of them showing that it would make little to no difference.

While the rate-review process will continue to unfold over the next two months, at this point it looks like the eventual outcome will be a national average rate increase that is in the single digits and close to the projected general increase in medical spending.

Therefore, whether or not Congress extends the enhanced subsidies will have very little effect on actual 2023 premiums. So, no, premiums will not “soar” if the enhanced subsidies aren’t extended.

It’s also important to understand how the Obamacare subsidy design operates and the temporary changes made by the COVID-19 spending bill.

Obamacare’s subsidy design specifies what the enrollee must pay directly—using a statutory formula based on the enrollee’s income—regardless of the premiums charged by insurers. The government then calculates the difference between that amount and the premium for the reference plan (the second-lowest cost silver plan) where the enrollee lives. The result is the amount of subsidy the government will pay to the enrollee’s chosen plan.

In fact, Obamacare’s subsidy system was deliberately designed to keep what the enrollee pays constant, regardless of how much premiums increase.

The COVID-19 spending bill simply changed how much enrollees are expected to contribute to the cost of their coverage by temporarily changing the formula.

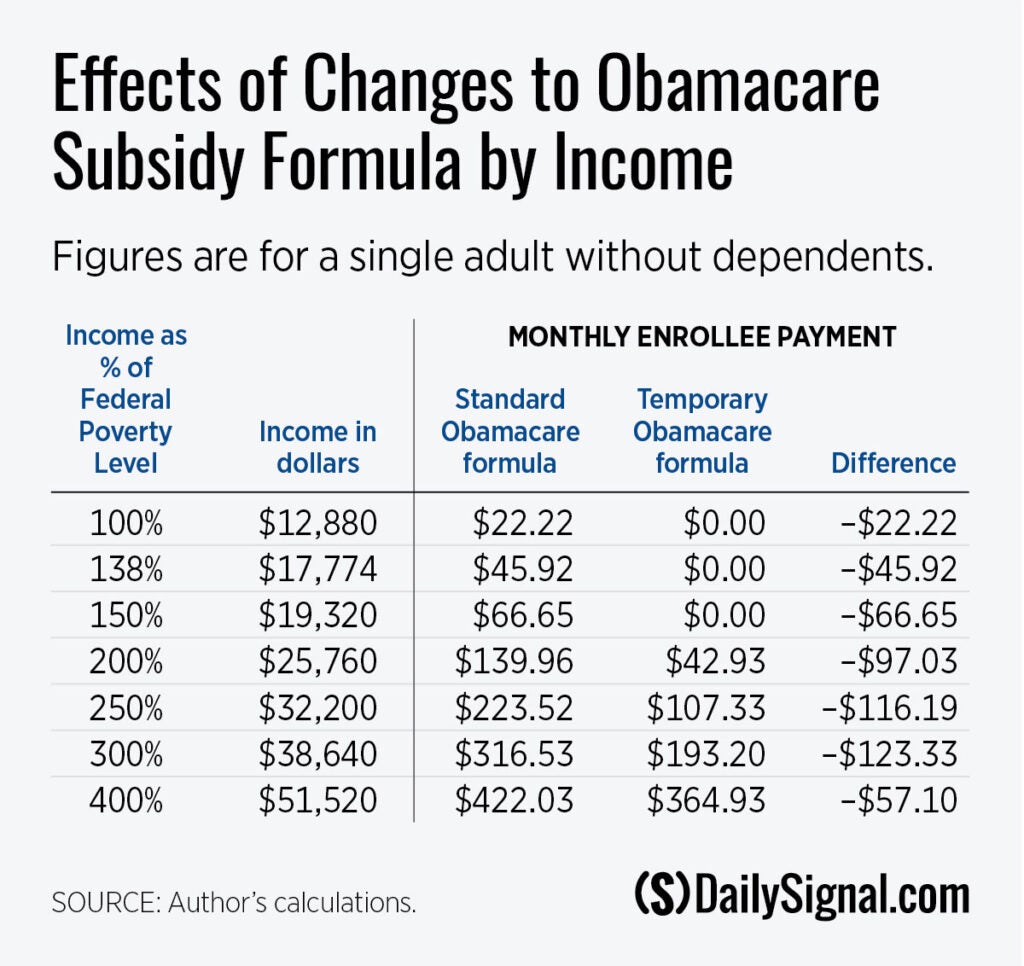

As can be seen from the following table, the temporary change in the formula only modestly reduced premium payments for most enrollees. That was particularly the case for the lowest-income enrollees (those below 150% of the federal poverty level), who already paid very little for their coverage under the standard formula.

That group accounts for 40% of enrollees, while 30% of enrollees have incomes between 150% and 250% of the federal poverty level. Few if any in those groups are going to drop their coverage just because they must resume paying the nominal amounts that they willingly paid only two years ago.

The only group for whom the temporary change had a significant effect were the 10% of enrollees with incomes above 400% of the poverty rate (who were previously not eligible for Obamacare subsidies). That translates into annual household incomes above $50,000 for an individual, $70,000 for a couple, or $106,000 for a family of four.

Under the standard Obamacare formula, those enrollees don’t get any subsidies and must pay directly the full cost of their coverage. The temporary formula expanded subsidies to this new group so that they only had to pay an amount equal to 8.5% of their income, with the rest covered by subsidies paid to their insurer.

While it is likely that at least some of them got substantial subsidies under the temporary formula, it’s important to remember that this subgroup consists of middle- and upper-income enrollees, the vast majority of whom were already buying coverage without Obamacare subsidies.

Furthermore, those enrollees are primarily of self-employed, and thus have the option to instead claim an income tax deduction for their health insurance premiums.

They are also Obamacare’s most dissatisfied customers. They are unhappy not only because they are paying more, but also because, relative to their pre-Obamacare plans, they are paying more for worse coverage—consisting of plans with high deductibles and limited choice of doctors and hospitals.

What they really want is their previous—and better—coverage back, not just bigger subsidies for inferior Obamacare plans.

All of the foregoing explains why the Congressional Budget Office viewed the enhanced subsidies as having virtually no effect on the number of people with individual market health insurance coverage.

In sum, extending the temporary bump-up in Obamacare subsidies by three more years will pointlessly throw another $64 billion onto the inflation bonfire in exchange for virtually no societal benefit.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email [email protected] and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the url or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.