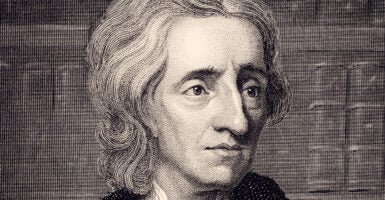

Arguably no philosopher had a greater influence on America’s founding than John Locke, says Joseph Loconte, director of the Center for American Studies at The Heritage Foundation.

Locke’s ideas about property and freedom helped to shape America as the Founders drew on his ideas when they wrote the nation’s founding documents.

“[T]here was no philosopher who was quoted more often than John Locke by the American revolutionaries,” Loconte told “The Daily Signal Podcast.”

An expert on Locke, Loconte is presenting a paper this week on the English philosopher and the biblical roots of American democracy at the virtual John Locke Conference in Naples, Italy.

Loconte joins the show to discuss what advice Locke (1632-1704) would offer to America today and why the philosopher’s writings remain so relevant to the American experiment.

We also discuss these stories:

- The Biden administration rescinds former President Donald Trump’s executive orders targeting the Chinese-owned apps TikTok and WeChat.

- Former President Barack Obama praises his daughters, Malia and Sasha, for their social activism.

- The New York Times comes under criticism after editorial board member Mara Gay tells MSNBC that seeing “dozens of American flags” on Long Island was “disturbing.” The newspaper insists she was “taken out of context.”

Listen to the podcast below or read the lightly edited transcript.

Viginia Allen: I am so pleased to be joined by Joseph Loconte, director of the B. Kenneth Simon Center for American Studies at The Heritage Foundation. Dr. Loconte is a New York Times best-selling author, a professor, and an expert on the 17th-century philosopher John Locke. Sir, thank you so much for being here.

Joseph Loconte: Virginia, great to be with you. Thanks for having me.

Allen: You’re a John Locke expert and you have just written an extensive paper on Locke, which we’re going to discuss in detail in just a moment. But first, for anyone who’s not familiar with John Locke, could you just give us a little bit of an explanation of who he is?

Loconte: Yeah. In many ways, Locke is considered the father of political liberalism, the ideas and the institutions we take for granted now in America.

For example, the principle of government by consent of the governed, the separation of powers, the idea of natural universal rights of freedom of conscience, religious liberty, property as being sacrosanct—these ideas, virtually all of them come out of Locke’s thinking.

He was certainly one of the most, if not the most, important English philosopher in the 17th century. He had a profound effect on the American founding, and I’m sure we’ll get into that as well.

Allen: So, the American Founders were looking to Locke as they were crafting many of those documents that became the Constitution, Declaration of Independence, that really founded our nation.

Loconte: Yes. I mean, the amazing thing about the Founders, of course, Virginia, is that they really studied the past intently to learn the lessons of history, in a way that no other political generation had done.

So yeah, they studied the classical Greeks, the Romans, the Greek tragedies, Rome as a republic. But then also these philosophers, like Locke, who are making these arguments for self-rule and self-government. And there was no philosopher who was quoted more often than John Locke by the American revolutionaries. So, he had a real significant influence.

Allen: And why was that? Why was Locke so much more significant than other philosophers of that time?

Loconte: That’s exactly the right question to ask. I’ve got a partial answer for you, because we can’t get into the minds of the Founders the way we’d like to. Why was Locke so appealing? I think several reasons.

One is, he had this ability to talk about these large political questions about human rights, natural rights. The idea of self-government. The idea of freedom of conscience. He could talk about it in a grammar that everybody could understand.

He was clearly friendly to the Christian religion. He’s not a radical enlightenment guy, like a Voltaire. He knew the Scriptures thoroughly. He wrote commentaries on the Epistles of Paul. I think he believed in the inspiration, the divine inspiration of the Scriptures.

So he’s operating more or less within this Christian tradition, but he’s using a grammar, a rhetoric, a style of argument that could appeal to people across denominations, across faith traditions. So he had an incredibly persuasive power with his most important writings.

Allen: And you have just written an extensive paper examining Locke’s “A Letter Concerning Toleration.” Could you just give us a brief summary of that paper?

Loconte: Yeah. This is for a Locke conference, an international Locke conference up in Naples, Italy. Unfortunately, it’s going to be a virtual conference.

Allen: Yeah, that is unfortunate.

Loconte: How tragic is that, Virginia? Thank you very much.

Allen: It is very tragic.

Loconte: As an Italian American, it’s pretty tragic, let me tell you.

But there’s going to be like 60-some odd scholars, Locke scholars, from around the world converging for this conference. And you ask yourself, “Wow, why do these people still care about John Locke?” Because he still speaks into our contemporary issues about rights, about self-government, about tyranny, freedom. He still speaks to us. So we’ve got all these scholars gathered.

My particular contribution, I’m going to focus on Locke’s “Letter Concerning Toleration,” and that’s his great defense of religious freedom.

I think Locke’s letter on toleration, published in 1689, so a hundred years before the American founding, … I think that document, not only was it transformative in its own day, I think it stands as probably the most important defense of religious freedom ever written.

Allen: Wow.

Loconte: That’s the kind of, I think, transformative effect it had on the 17th-century mind and well into the 18th century. And certainly influenced the Founders like Madison, Jefferson, as they were thinking about the issue of religious liberty.

Allen: For Locke, how did biblical teachings and the life of Christ come to influence him so deeply?

Loconte: Yeah, that’s in part what I’m going to address in the paper here. I think not enough scholars have given enough attention to the religious influences on Locke’s thinking, particularly on his “Letter Concerning Toleration.” And what I’m going to argue in this paper is, there was an earlier reform movement called Christian humanism.

A Catholic thinker named Erasmus of Rotterdam, who was a contemporary of Martin Luther—so you’re talking 1517, 1520s. Erasmus had put a real emphasis on the inner life, the life of the heart, the life of the soul, as opposed to outward religious observances or dogmas. He said, “You got to imitate life of Jesus.”

This is basically Erasmus and this Christian humanism, and as a bringing together of the intellectual and the heart, the mind and the heart with the Christian humanists. That movement didn’t die with Erasmus.

That movement, it took root in different places in Europe—in Great Britain and also in the Netherlands. And those two places were actually very important to Locke.

He’s an English philosopher. He finds these Christian humanist followers there in Great Britain. He’s reading their sermons, he’s going to their churches, he’s befriending them. And then in the Netherlands, when he’s in political exile, he meets really the successors to Erasmus in the Netherlands with that same spirit, imitate the life of Jesus and apply the principles of the life of Jesus to civic and political life.

So what do I mean by that? Something real concrete. The golden rule, right? Treat others as you want to be treated. What Locke is saying in so many ways, especially on this issue of religious freedom, it’s the civic application of the golden rule: equal justice under the law. Treat everyone the way you want to be treated, regardless of religious belief, religious commitment.

Equal treatment under the law, it’s the political application of the golden rule. That’s one example of how [these] Erasmian Christian humanist ideas, I think, found their way into Locke’s thinking.

Allen: Yeah. And [they] obviously found their way into the American mentality in the South. So today, how are we doing storing those things, those principles that Locke really so promoted, and that the Founders took hold of? Are we continuing to store really those biblical principles that then found their way into our laws? Are we doing that well?

Loconte: That’s a $95,000 question, which is above my pay grade. No. Look, if you take the issue of natural rights, which Locke was a real pioneer in making the case that everybody has these universal natural rights—life, liberty, and property. Those are the big three categories for Locke—life, liberty, property.

And property meant not just your physical property, but the fruit of your labor, the fruit of your creative efforts. That’s your property, too. Your intellectual property is your property, too.

How are we doing in protecting those natural rights? Well, if you think about the 20th century, for example, which has been called by [Aleksandr] Solzhenitsyn, has been called the caveman century, the great assault on human rights, natural rights, the challenge we have now, I think, Virginia, one of them is we don’t even understand what natural rights are. We’ve so confused “human rights.” Everything is a human right. We’ve confused natural rights with social aspirations.

For example, we’d like to have a country where people have access to quality health care. … Is that a human right? Is that a natural right? Or is it a social aspiration? I would argue it’s an aspiration.

And yet the confusion of these things, the things you’d like to see happen in society with your natural God-given rights, that confusion, that blurring of things, that has just invited all kinds of government mischief. The kind of thing that Locke would have been firmly opposed to, it seems to me.

Allen: You say that the recovery of Locke’s singular moral vision is one of the most urgent cultural tasks of our day. What was that vision that Locke had? And how do we go about achieving that?

Loconte: If I could put it in a couple of sentences, I’ll try, because I tend to be long-winded, but I will try. The obligation, the responsibility, and the freedom of every person to seek after truth, according to the dictates of conscience, without the interference of church or state, this is one dimension of his singular moral vision.

Locke really believed that this, that the quest for truth, moral truth, spiritual truth, this is the most important quest anyone could be on in their life. And government’s prime responsibility was to create the civic space necessary for people to pursue truth.

So they have to have freedom, civic freedom, religious freedom. All of that is tied up with self-government. If you don’t have a political system that respects the individual’s quest, the individual capacity to govern himself, herself, then you’ve got a society that’s in crisis, and we’re edging in that direction you could argue.

Allen: Yeah. How would Locke say that we’re doing today?

Loconte: I think the assumptions that people’s rights and freedoms are negotiable because a government official says they are, if we think about the way we’ve responded to the COVID crisis—I’m not saying that there haven’t been real challenges and real issues, and a real need for concern and measures being taken. But you could easily argue that there has been an overstepping of political power.

The will to power, I think, has resurfaced in a way that I think is shocking to many Americans. The limitations on our liberties that have no rational defense in science, in civics, in our Constitution. And yet here they are still. We’re still living with them. I think Locke would look at that and be appalled at the erosion of human freedom, human liberty.

Allen: So you don’t think it would have been something he would have foreseen, this kind of natural ebb and flow, or do you think he really would be quite surprised by what he sees?

Laconte: Well, that’s a great question. I mean, Locke’s “Second Treatise”—I’m holding it up right now for you to see. Locke’s “Second Treatise” … was the document that really set the American revolutionaries on fire, because what he does in the “Second Treatise,” he lays out the case for natural rights—life, liberty, and property. And he says, “Governments are instituted to protect those rights.”

That’s why we elect people. That’s why we surrender a measure of our own sovereignty to the government to protect those rights.

And the “Second Treatise” says, “Once government, after a long train of abuses,”—that’s his phrase, also becomes the phrase of the American revolutionaries—” … if government violates those rights, you have the right to revolt.” He lays out a natural law, natural rights argument for political revolution. That is a firebomb that goes off with the American revolutionaries.

I mean, they’re carrying around the “Second Treatise.” It is quoted from pulpits throughout the Colonies in America on the eve of the Revolution. So … I think Locke expected governments to act in a way that would be tyrannical. And he’s laying out a condition by which you overthrow that government, if it comes to that.

But he was hopeful that we could create a liberal political regime. Other people will come along and flesh out that idea—Montesquieu and the separation of powers and others—but Locke is laying the groundwork for, “This is what governments do. They protect your life, liberty, and property.”

Allen: Wow, wow. So considering your paper and kind of, as you’re putting this message forth, what’s your hope that those who read it, who study it, what do you want them to draw from it?

Loconte: A terrific question. Thanks for asking it. I think that the religious influences on Locke’s political thinking have been underrated, and there’s debate going on, even right now within conservative circles.

There are some conservatives on the far right who see Locke as an enemy of tradition, and an enemy of religion. An enemy of a decent, normal, humane life. I think they’ve got Locke completely wrong.

I think the religious influences, the Christian influences on Locke are profound. You can’t miss it in his writings. So I think there’s a great resource there in Locke, in his ability to blend reason and revelation to make arguments for our natural universal rights. There are just tremendous moral resources there with Locke.

I want to see a kind of, a new understanding about the American founding. That it didn’t grow out of a secular militant enlightenment. That’s what the radical left would like us to think. That’s what some, unfortunately, some ultra-conservatives believe, that the American founding was somehow a mistake from the start. It was the product of the radical French Enlightenment, absolutely false.

The American Revolution was a Lockeian revolution, meaning it was grounded in a deep respect for the trues of the Bible and a sober understanding of the limitations of the human condition. That kind of understanding says me, we could use a little bit more of that today, couldn’t we?

Allen: Yeah, we sure could. Do you think Locke would be discouraged if he landed in D.C. today and saw what was going on? Or do you think he’d roll up his sleeves and say, “All right, let’s get to work.”

Loconte: That is a fabulous question. I think he’d roll up his sleeves, and I think here’s the reason: He wrote the “Second Treatise,” in a sense, when he was on the run politically.

He was deeply involved in the political debates in Great Britain in the 1670s and ’80s, when they’re going through their own political absolutism and tyranny phase. And he is part of what becomes the Glorious Revolution in Great Britain in 1689, 1690, when … what does Great Britain do? They reaffirm constitutional government. And the new monarchs, William and Mary, willingly submit to Parliament.

That was a breakthrough, a breakthrough in human history for monarchs to say, “Yes, constitutional government.” Locke is part of that revolution. So he risks life and limb to be part of that revolution. That’s why he’s in exile in the Netherlands in the 1680s.

That’s when he writes his letter on toleration with another crisis, with the expulsion of the Protestants from France. A new wave of religious persecution there in Europe, and he’s in the midst of that.

So what does he do? He uses the tools that he has. He can write and he can think, and that’s what he does. And he pushes back with these great works that become the canon of the liberal political tradition.

His two treatises on government and his “Letter Concerning Toleration,” absolutely transformative documents, part of the canon. And they need to be taught and re-taught. And that legacy, it’s a great, rich inheritance we have, but I think even many conservatives are not quite aware of how rich that inheritance is.

Allen: Yeah. For those listening, thinking, “I want to learn more. I want to know more about what’s in this paper,” are they able to tune into that conference because it’s virtual? Do you know?

Loconte: Yes, they should be able to [attend the] conference, and they can send emails to me and I’ll send the link to the conference event. It’s on June 9 to June 11, virtually, in Naples, Italy.

Allen: Excellent.

Loconte: To me, it’s a powerful statement that this many Locke scholars are coming together. It shows the relevance of this English philosopher to our current debates. As far as I know, there’s nothing, there’s no conference like that going on about Voltaire. It’s Locke. The American Revolution was a Lockeian revolution. He still matters.

Allen: And for those who want to read your paper, how can they do that?

Loconte: Well, it will be online on the day of the conference. It’ll be available then, but probably not before.

Allen: OK. Excellent. Thank you so much. Anything you would like to add? Final thoughts?

Loconte: I just think we have this tremendous resource and legacy. And one of the reasons, as an historian, I love to remind us of the debt that we owe to the men and women who, at moments of crisis, didn’t throw in the towel. They didn’t cower. They didn’t go into hiding. They didn’t allow the establishment to cancel them. They just … went into the arena and they just made a difference that just ripples into our own day. That’s worth thinking about it.

Allen: Wow. Thank you so much for your time.

Loconte: Thank you.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email [email protected] and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the URL or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.