KYIV, Ukraine—Monday marks the 75th anniversary of the day Soviet soldiers liberated Auschwitz, Nazi Germany’s largest concentration and extermination camp. At Auschwitz, the Nazis murdered more than 1 million men, women, and children, mostly Jews, during the Holocaust.

I have been to Auschwitz only once. It was a long time ago, in February of 2006.

I lived in Paris at the time, attending graduate school at the Sorbonne as part of a military fellowship before Air Force pilot training.

We had a few weeks off in February, so a friend and I embarked on a road trip across Eastern Europe. In Prague, we split up for a few days. I’d wanted to visit Krakow, Poland, and Auschwitz. My friend didn’t. So, I hopped on a train and we agreed to reconvene in Vienna a few days later.

The thing is, I was drawn to Auschwitz. For me it was a monument, symbolizing that wars are sometimes necessary. And at that time, war cast a long shadow over my life, even while I was having the time of it while living in Paris as a young man.

The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were then in full swing, and I was a newly minted Air Force second lieutenant, having graduated from the Air Force Academy in June of 2004.

And so, while most of my friends had gone straight off to training programs for their future career fields, getting ready for war, my superfluous days were spent reading and writing in Parisian cafes, enjoying the famous French wine and food—with the odd university class thrown in the mix from time to time.

By February of 2006, some of my friends were flying fighter jets. Others had already experienced combat. And yet, there I was, nearly two years on active duty, about to make rank automatically as a first lieutenant. And I’d done nothing more than easy living in Paris.

But I got a hard dose of reality one weekend night.

I was in line for a Paris nightclub, and the two men in front of me were speaking in English, using acronyms and lingo that quickly gave them away as members of the U.S. military. We got to talking, and I let them know I was an Air Force lieutenant slated to begin pilot training in the fall of 2006. I thought they’d be impressed. They weren’t.

They said they were enlisted Army soldiers on leave after a tour in Iraq. Then they asked if I’d ever deployed. I said no and felt smaller than I ever had before.

Yes, living in Paris was a gift, and I was grateful for the experience. But I just couldn’t shake the feeling that I should be out there fighting in my country’s wars.

Thus, it was in this frame of mind that I decided to part ways with my friend in Prague and take a night train to Poland. I’d also just recently watched the movie “Schindler’s List” for the first time. Fresh, haunting images from that film were forefront in my mind when I stepped off the train in Krakow.

It was night, and I walked the streets alone and in the dark. A thick layer of snow covered the ground. The air was painfully cold.

I went first to Oskar Schindler’s Enamel Factory, where the legendary German industrialist had sheltered Jews during the Holocaust. From there, I strolled Krakow’s streets late into the night, trying to imagine what had happened there during the war. The city was quiet and still as most cities are at night, and I felt like I had the place to myself.

And yet, that nagging sense of guilt was always there, chasing me like Pigpen’s dust cloud. The unforgettable truth that at that moment my friends were at war, and I wasn’t.

The next day I took a train from Krakow to Auschwitz. It wasn’t a long ride, and I arrived early in the morning and took a taxi from the station to the Auschwitz I camp.

Like in a scene from Dante, I walked into the camp through the metal gate infamously crested by the German words: “Arbeit macht frei.”

Work sets you free.

Originally Polish army barracks, the Nazi SS had used Auschwitz I at first to house Polish political prisoners. At the site, the Nazis later built gas chambers and a crematorium for the mass murder of Jews and other minorities.

The day was clear without a cloud in the sky. But it was cold. A kind of unforgiving cold that cuts easily through piled-on layers of down and fleece. My fingers moved in slow motion as I tried to work my camera.

My thoughts, too, seemed to be stuck at some slower pace. But that lethargy had nothing to do with the cold. Rather, as I went deeper into the camp, and as I encountered mounting evidence of what had happened there during the Holocaust, my mind simply could not keep up with the horror of it all.

The real-world implications of what I was seeing were beyond the limits of my 23-year-old imagination, which had not yet been shaped by war, to appreciate.

Yes, I’d seen movies and read books about the Holocaust. But at that moment I was walking through the place where it had all actually happened. The epicenter of humanity’s greatest crime.

I went into the old brick buildings and saw rooms filled with eyeglasses, shoes, clothes, random knick-knacks. All stolen from prisoners before their executions in the gas chambers. The piles of these things were depressingly huge.

There was a gas chamber and crematorium left standing at the Auschwitz I complex. When I went inside my eyes gravitated toward the walls and the ceiling—the edges of that horrible space. Subconsciously, my mind wanted out.

I caught another taxi for the two-mile trip to the larger, Auschwitz II-Birkenau compound.

From pictures, I instantly recognized the front tower at Auschwitz II-Birkenau, and how the narrow-gauge railway line ran underneath the tower into the center of the camp where prisoners were unloaded from cattle cars and the Nazi SS guards decided who lived and who died.

I walked alone through the ruined camp. I’m sure other people were around, but I saw no one.

The day, as I’ve said, was cold beyond cold. My feet crunched in the snow. My fingers burned and then went numb. I felt guilty, though, when I considered cutting my visit short to seek warm shelter. The prisoners had once endured equally cold conditions, and under infinitely more trying circumstances.

I walked to the rear of the camp and stood at the edge of a ramp that led down to what had once been a building housing gas chambers. In an attempt to hide their crimes, the Nazis had demolished the gas chambers before the Soviets arrived. On that day in 2006, the structures were nothing more than piles of rubble covered in snow.

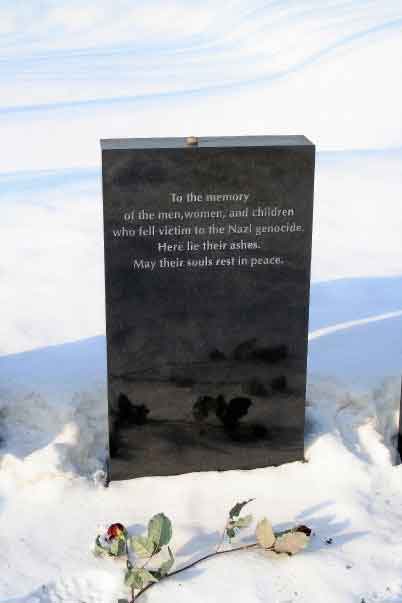

Nearby where I stood, a black stone monument stood amid an unblemished blanket of snow. The stone was engraved with the words:

To the memory of the men, women, and children who fell victim to the Nazi genocide. Here lie their ashes. May their souls rest in peace.

Gravity seemed heavier on this spot. The weight of the knowledge of the tragedy that had happened here added mass to the earth and air.

It wasn’t an exceptional place. Just a heap of bricks under the snow. But the suffering that the ground concealed was radioactive. It hummed and crackled, passing invisibly through the air, then right through me, turning me inside out, damaging me from within.

You can’t see it, touch it, or smell it. But you feel it. And there’s a particular way the hushed voices of the dead echo to the living in a place like Auschwitz.

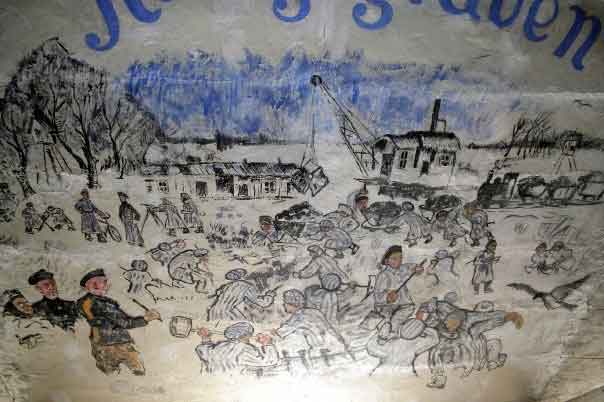

Later, I moved on and looked into the prisoners’ barracks. It was unimaginably cold inside where the prisoners had once slept—where at night they’d clung to their slim hopes for survival. I ran my hand over a graffiti mural a prisoner had drawn on a wall. I tried to imagine life as a prisoner at Auschwitz. I couldn’t.

Before I left Auschwitz II-Birkenau, I came upon two roses tied to a barbed-wire fence. The red petals stood out sharply against the snow. The flowers had not wilted; someone had left them there recently. I looked around but saw no one.

Standing before the roses, I thought, “Thank God there are good people, too.”

Then I proudly remembered my friends who were at war. And more than ever I wanted to join them in the noble effort of preventing something like Auschwitz from ever happening again.

More than 10 years later, I stood at the edge of a field in Sinjar, Iraq. A pile of human bones was in the field. Evidence of another genocide—the Islamic State’s mass murder of Yazidis, Christians, and Shiite Muslims.

By then, in June of 2016, I’d already served in both Iraq and Afghanistan as an Air Force special operations pilot. And I’d been back to both those wars as a civilian war correspondent. I’d spent a lot of time on the front lines in Ukraine, too.

Now I knew what war looked like from both the ground and from the air. I knew a lot more about war than I’d ever thought I’d know. And yet, despite my education in the horrors of war, there I was once again, totally incapable of understanding what quantity of evil could ever permit a human being to prosecute the mass murder of innocents.

I stood there in silence alongside dozens of Kurdish peshmerga soldiers. Those brave warriors were, at that time, engaged in ongoing combat against the Islamic State’s terrorist army. In fact, the Islamist militants were entrenched only a couple miles from where we then stood.

The fighting was close enough to hear. And in the sky, U.S. warplanes—piloted by men and women of my generation, some of whom I knew—were also killing our mutual enemies. Amid the background din of distant gunfire and American jet noise, I thought back to that cold day at Auschwitz a decade earlier.

I remembered that the ruins of Auschwitz’s gas chambers are not, after all, evidence of evil’s defeat. Rather, those ruins remind us that the fight is never over. Every generation has its own responsibility to keep evil at bay. And mine is no exception.

As we reflect on the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, it’s easy to be lulled into the mistaken belief that history automatically arcs in the right direction. That the era of world wars and genocides is over. That it could never happen again.

But the truth is we are just treading water, fighting against the gravitational tug of history. The minute we stop kicking, we descend, quickly and easily, into those dark depths from which we thought we had escaped.

To defeat evil, we must remember that it exists. And to prevent another Auschwitz from ever happening again, we must believe that it could.