The president’s critics thought his presidency was illegitimate to begin with. His Cabinet members changed frequently. Mainly based on policy disagreements, members of Congress demanded his ouster.

Some lawmakers were willing to toss out constitutional norms based on what they said was the president’s “ignorance of the interest and true policy of this Government, and want of qualification for the discharge of the important duties” of his office.

But we’re talking 1843, not 2019.

In the midst of House Democrats’ impeachment inquiry targeting President Donald Trump, many pundits make comparisons to the impeachments of Presidents Andrew Johnson in 1868 and Bill Clinton in 1998, as well as the near-impeachment preempted by President Richard Nixon’s resignation in 1974.

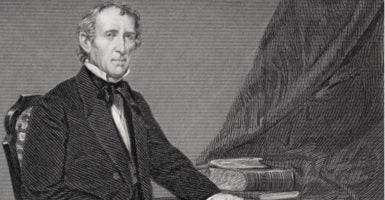

But lawmakers’ first serious effort to impeach a president was against President John Tyler in 1843. And it didn’t succeed, not even in the House.

The attempt to impeach Tyler had some similarities to the Johnson impeachment: A vice president—with a history in the opposition party—takes the top job upon a president’s death but fails to get along with the elected president’s party in Congress.

The Whig ticket of William Henry Harrison and John Tyler—“Tippecanoe and Tyler too”—won by a decisive landslide in the 1840 election. Harrison scored 234 electoral votes and 53% of the popular vote to oust President Martin Van Buren, the unpopular Democrat, who collected just 60 electoral votes.

Harrison, a former Ohio senator, was known as “Tippecanoe” for his military heroism against Native American forces in the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe in Indiana.

For vice president, the Whigs tapped Tyler, a former Virginia governor and U.S. senator. He was a Whig convert after leaving the Democratic Party in protest of President Andrew Jackson’s policies.

Harrison died one month after taking office, thrusting the United States into uncharted waters. Harrison’s Cabinet insisted that Tyler was only an acting president, but Tyler established a precedent that would hold by asserting that a vice president automatically moves into the presidency upon a vacancy in the office.

At 51, Tyler was younger than any other president before him.

The Whig-controlled Congress passed legislation to reestablish a national bank, which was the party’s biggest legislative goal. Tyler vetoed the bill, and seemed intent on blocking the fruition of other Harrison campaign promises. This enraged his fellow Whigs in Congress.

After Tyler’s veto of the bank bill, the Whigs voted to expel the president from their party—though he was still in office. And when Whigs resigned from his Cabinet, Tyler named Democrats to the vacant posts.

The frustration caused Rep. Henry Clay of Kentucky, a prominent Whig leader, to propose a constitutional amendment to allow Congress to override the president’s vetoes by a mere majority vote, rather than a supermajority. Despite Clay’s power in Congress, however, the measure went nowhere.

What really irked those in Tyler’s adopted party was his veto of two bills imposing higher tariffs on imported goods.

One Whig lawmaker accused Tyler of seeking to bring back “the condemned and repudiated doctrines and practices of the worst days of Jackson’s rule.”

That was a severe assessment, considering the unifying ideology of the Whigs was opposition to Jackson.

Before Jackson’s presidency, Congress was viewed largely as the policymaking body, and a president was expected only to veto legislation if he thought it unconstitutional, not because he disagreed with it.

So Whigs accused Jackson of wanting to be a king because of his vetoes, and they weren’t happy when the president elected on their own ticket began doing the same thing.

On July 22, 1842, Tyler’s fellow Virginian and Whig, Rep. John Minor Botts, filed the first formal action in the history of the House of Representatives to impeach a president of the United States.

Botts presented a resolution, requesting “John Tyler, the acting President of the United States,” resign his office. Failing that, the resolution said, Tyler should be impeached “on the grounds of his ignorance of the interest and true policy of this Government, and want of qualification for the discharge of the important duties of President of the United States.”

The resolution called for a special committee to investigate possible charges of impeachment recommendations. The House initially tabled the resolution for further consideration, as Clay thought it premature.

That wasn’t the end of the Tyler impeachment effort, however.

Rep. John Quincy Adams, a Whig from Massachusetts and a former president himself, was chairman of a select committee that approved a resolution in August 1842 condemning Tyler’s “misuse” of the veto. The select committee’s action set up the possibility for impeachment.

Finally, in January 1843, the Botts impeachment resolution came to the House floor. The Whig majority, although not fond of Tyler, ultimately wasn’t quite ready to enter the realm of impeachment and possible removal by the Senate.

The House rejected the motion to investigate Tyler for the impeachable offenses of “corruption, malconduct, high crimes and misdemeanors,” by a vote of 127-83.

Despite his tumultuous relationship with Congress, Tyler had some significant accomplishments while serving most of the term that Harrison won—in particular the annexation of Texas. Tyler also pushed through the Webster-Ashburton Treaty to end a Canadian boundary dispute.

Tyler formed his own party, the Democratic-Republicans, in hopes of winning the presidency again but in the end dropped out of the 1844 race. But that’s another story.

The nation’s 10th president died in 1862 while serving as a member of the Confederate Congress.