The recent electoral race between Republican Karen Handel and Democrat Jon Ossoff in Georgia’s 6th Congressional District was the most expensive ever for a seat in the House of Representatives.

In all, $57 million were spent, approximately $27 million more than the next most expensive race.

The sheer cost of the race has brought a favorite theme of the left back to the fore: the purportedly corrosive role of money in politics.

For decades, left-leaning pundits and Democratic politicians have warned of the compound effect of Supreme Court rulings like Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, which loosened legal restrictions on campaign contributions, and rising income inequality, which allows a few very wealthy citizens to make very large donations.

As The New York Times’ Paul Krugman puts it, “[We live in a] society in which money is increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few people, and in which that concentration of income and wealth threatens to make us a democracy in name only.”

President Barack Obama, who called rising inequality “the defining challenge of our age,” worries that an influx of campaign contributions from the very wealthy “distorts our democracy. It gives an outsized voice to the few who can afford high-priced lobbyists and unlimited campaign contributions, and it runs the risk of selling out our democracy to the highest bidder.”

These exaggerated claims rest on two major premises:

- The rich and poor have divergent and conflicting interests.

- Campaign contributions, combined with expensive lobbyists, allow the rich to shape policy to match their desires.

But, as I make clear in my recent backgrounder, “Does Rising Inequality Threaten Democracy?” the empirical evidence supporting these claims is surprisingly weak given the ubiquity of the belief that wealthy donors have become a caste of oligarchs.

In fact, the data show that the upper, middle, and lower class do not differ very much in their policy preferences.

Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page, professors at Princeton University and Northwestern University, respectively, who conducted one of the most frequently cited studies on the alleged political power of the rich, find that the preferences of high-, median-, and low-income earners are “fairly highly correlated.”

This is actually a significant understatement. The correlation between the policy preferences of the top 10 percent of income earners and median income earners is 0.94 (a correlation coefficient of one would indicate identical preferences).

In fact, according to the surveys analyzed by Gilens and Page, a majority of all three classes—high, middle, and lower—agree on 80 percent of policy questions.

Part of the reason the political divisions on the basis of class are weak in America is that other factors—such as race, religion, region, gender, and age, to name a few—are more predictive of policy preferences that cut across class lines.

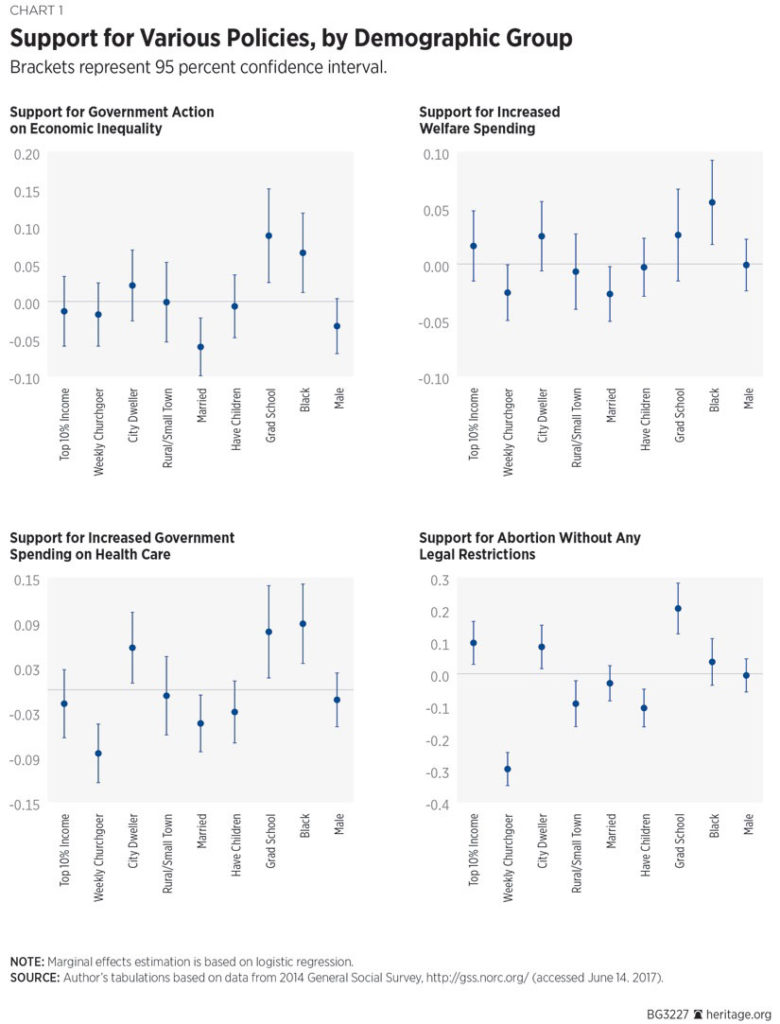

As the graphs above illustrate, when other important factors are taken into consideration, income generally ceases to be relevant to political opinions.

Even when it comes to support for government action on economic inequality and welfare spending—policy considerations that would seem to pit rich again poor—factors like race, religion, marital status, and education level are more predictive of political attitudes.

When a policy question does divide opinions along class lines, studies show the influence of the upper and middle class is nearly identical. When high- and middle-income earners prefer opposing policies, policymakers side with each group about half the time.

Even the poorest Americans are sometimes able to exert influence in Washington when their interests are opposed by both the upper and middle classes. In these cases, the lowest quintile of income earners achieve their policy objectives nearly 20 percent of the time.

Taking a step back from the academic research, the conclusion that the rich dominate in Washington does not line up with the broad trajectory of federal policy.

Look at the size and scope of the welfare state and the distribution of the tax burden, it appears as though the federal government is taking its cues from low- and middle-income earners, at least on macro-level economic policy.

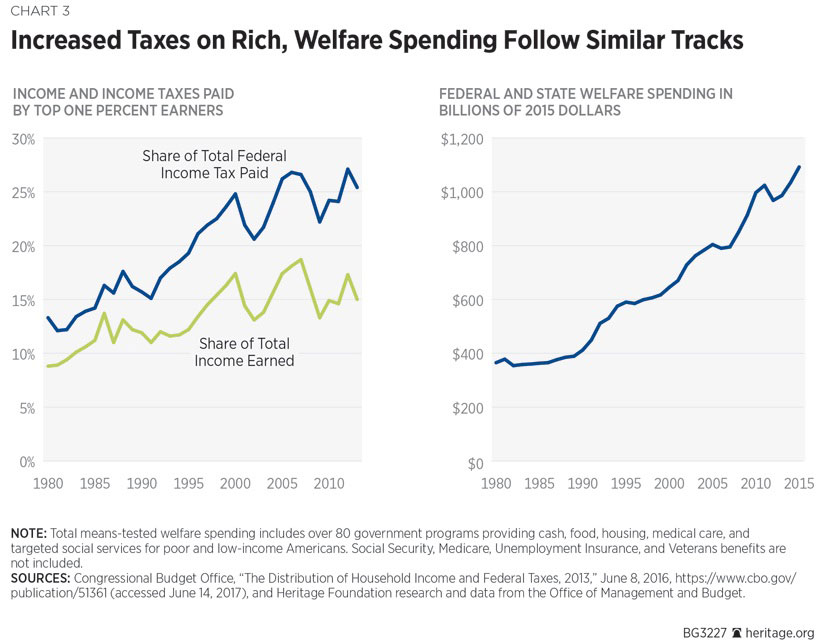

While the share of total income earned by the top 1 percent has grown, their share of the tax burden has increased even faster. Meanwhile, low- and middle-income earners are asked to pay a dwindling portion of the cost of running our outsized federal government.

In recent years, the top 0.1 percent of income earners paid more in taxes than the bottom 80 percent combined.

At the same time, the welfare system is growing in size and scope with federal, state, and local expenditures now totaling over $1 trillion annually.

In short, the rich are paying a larger share of their earnings to fund programs they either do not need or are not eligible for. This is not what oligarchy looks like.

This does not mean that everyone’s voice is heard equally in Washington or that John Q. Public has the same relationship with his congressman or senator as Sheldon G. Adelson or George Soros. Big donors certainly gain access to policymakers as a result of their contributions.

However, the access some wealthy individuals enjoy has not had the result left-leaning pundits claim. Policymakers do not simply ignore the poor or middle class in order to curry favor with the rich.

After all, brimming campaign war chests cannot overcome a failure to connect with average voters—a fact Ossoff and Hillary Clinton can attest to.