In the 2016 presidential election, one candidate is warning about voter fraud, while another proclaims Russians are interfering. It’s not the first time contenders have alleged some form of a “rigged” election.

In my book, “Tainted by Suspicion: The Secret Deals and Electoral Chaos of Disputed Presidential Elections,” I write about some of the most controversial presidential elections that left large segments of the population believing their president was selected instead of elected. In two elections, the aftermath nearly led to mass violence.

Tuesday in the Rose Garden, President Barack Obama dismissed concerns of fraud this year.

“I have never seen in my lifetime, or in modern political history, any presidential candidate trying to discredit the elections process before votes have even taken place. It’s unprecedented,” Obama said.

“There is no serious person out there who would suggest somehow that you could even rig America’s elections, in part because they are so decentralized and the number of votes that are cast,” the president added. “There is no evidence that has happened in the past, or instances that will happen this year.”

While such complaints have been rare before votes were cast, they were very prominent in certain post-presidential elections, as was evidence that votes weren’t always counted properly.

“There is no serious person out there who would suggest somehow that you could even rig America’s elections,” @Potus says.

Here are excerpts from the book.

1800: John Adams vs. Thomas Jefferson/Thomas Jefferson vs. Aaron Burr

James Monroe, who was aligned with the Democratic-Republican faction led by Thomas Jefferson, worried about reports that Jefferson supporters were arming for revolt, and said, “Anything [like] a commotion would be fatal to us.” Jefferson much preferred a convention to amend the Constitution if the opposing Federalists continued down this road.

Though it would be Alexander Hamilton who would play a massive role in the outcome, there was a great flurry of activity that led up to the final result. Moderates in both camps didn’t want to see the country torn apart should the die-hard Federalists push it to the deadlock and try to appoint a president. …

Thousands poured into Washington, prepared for partisan violence if there was what the Jeffersonians called “usurpation.” President John Adams would assert years later, “ … a civil war was expected.”

Benjamin Franklin’s cautionary words, “A Republic, if you can keep it,” were put to the test. As it turned out, Americans could keep it.

Flaws and all, these were men with enough character and intellect to realize the folly of clinging to power or risking bloodshed to obtain it. The nation truly could have been on the brink of collapse while still in its infancy.

1824: John Quincy Adams vs. Andrew Jackson

On Feb. 14, 1824, Henry Clay accepted the offer of the President-elect John Quincy Adams to serve as his secretary of state—presumably making him the next heir apparent since the last four men to lead the State Department became president.

Andrew Jackson and his supporters immediately called this a “corrupt bargain” between Adams and Clay.

The enraged Jackson said Speaker Clay approached him with a similar offer—to make him president in exchange for Jackson appointing him as secretary of state. As Jackson told it, he had too much character to accept such an offer. So Clay went to Adams with the same offer and received a different answer.

Clay and Adams denied that any deal was made. Clay even demanded a congressional investigation into the allegations, which found no proof. It is one of those things that can be difficult to prove or disprove if no witnesses were present for those meetings. Above all, having those meetings to start with seems a miscalculation on the part of Adams who should have known it might look suspicious.

That said, there is no question who Clay preferred between the two. The only real question is who was telling the truth, Jackson or Clay, on the charge that he made the same offer to both rivals. Clay considered the optics of becoming secretary of state as well, he later told friends, but thought he couldn’t reject the nomination because: “It would be said of me that, after having contributed to the elevation of a president, I thought so ill of him that I would not take first place under him.”

1876: Rutherford B. Hayes vs. Samuel Tilden

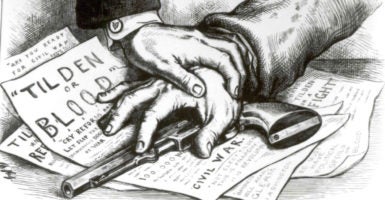

Henry Watterson, publisher of the Louisville Courier-Journal and a Democratic congressman from Kentucky, on Jan. 8, 1876—which he called “St. Jackson’s Day” because it marked the Battle of New Orleans—called for “the presence of at least 10,000 unarmed Kentuckians in the city” to march on Washington to ensure Samuel Tilden was elected.

His friend Joseph Pulitzer, still building a vast newspaper empire, went further, calling for 100,000 people “fully armed and ready for business” to ensure that Tilden became president.

Angry Democrat mobs across the country would chant, “Tilden or blood,” and reportedly in a dozen states, club-wielding “Tilden Minutemen” had formed threatening to march into Washington to take the White House for their candidate. This came to Tilden’s chagrin, who sought to calm the rowdiness, as he didn’t want to be responsible for an insurrection.

Still, with all the bellicose verbiage from the newspapers and the masses, it was the Democrat hierarchy in the South that was ready to make a deal, though not the Northern Democrats.

Richard Smith of the Republican Cincinnati Gazette reached out to Southern powerbrokers.

Rutherford Hayes asserted to Smith in early January 1877: “I am not a believer in the trustworthiness of the forces you hope to rally.” But, he told the newspaperman he did back internal improvements and education funding in the South believing it would “divide the whites” and help “obliterate the color line.” …

On the night of Feb. 26, 1877, four Southern Democrats, Reps. John Y. Brown and Watterson of Kentucky, Sen. J.B. Gordon of Georgia, and Rep. W. M. Levy of Louisiana, met with Ohio Republicans James Garfield and Charles Foster, both House members, and Ohio Sen. Stanley Matthews and Ohio Senator-elect John Sherman at the Wormley House hotel in Washington to see if a deal could be reached to prevent the House Democrats from blocking the results with a filibuster.

The men talked about details through the night, and by morning agreed to stop the House Democratic delay tactics that were blocking the certification of the Electoral Commission’s findings, on the condition of ending Reconstruction, appointing a Southern Democrat to the Cabinet, and providing federal money for southern projects. These were things Hayes expected to do anyway.

1960: John F. Kennedy vs. Richard Nixon

Earl Mazo, a Washington reporter for the New York Herald Tribune, began his investigation after he said Chicago reporters were “chastising” him and other national reporters for missing the real story.

He traveled to Chicago, obtained a list of voters in the suspicious precincts, and began matching names with addresses. Mazo told The Washington Post: “There was a cemetery where the names on the tombstones were registered and voted. I remember a house. It was completely gutted. There was nobody there. But there were 56 votes for [John F.] Kennedy in that house.”

Mazo also found that Chicago Mayor Richard Daley’s charge that other counties were doing the same thing in favor of Republicans proved to be true—but nothing on the scale of what happened in Chicago.

In Texas, Mazo found similar circumstances.

The New York Herald Tribune planned a 12-part series on the election fraud. Four of the stories had been published and were republished in newspapers across the country in mid-December.

At Richard Nixon’s request, Mazo met him at the vice president’s Senate office, where Nixon told him to back off, saying, “Our country cannot afford the agony of a constitutional crisis” in the midst of the Cold War.

Mazo didn’t back off and Nixon called his editors. The newspaper did not run the rest of the series. “I know I was terribly disappointed. I envisioned the Pulitzer Prize,” Mazo said. …

The entire matter wasn’t void of accountability.

Illinois state special prosecutor Morris Wexler, named to investigate charges of election fraud in Chicago, indicted 677 election officials, but couldn’t nail down convictions with state Judge John M. Karns.

It wasn’t until 1962 when an election worker confessed to witness tampering in Chicago’s 28th Ward that three precinct workers pleaded guilty and served jail sentences.

Pulitzer-winning journalist Seymour Hersh reported hearing tapes of FBI wiretaps about potential election fraud. Hersh—whose books indicate he is a fan of neither Kennedy nor Nixon—believed Nixon was the rightful winner.

2000: George W. Bush vs. Al Gore

Al Gore campaign aide Bob Beckel intended to make that moral case to Florida’s electors—and perhaps electors in other states—who could be convinced to follow the will of the people. Gore did not need all of the state’s electors, just four.

For that matter, he didn’t think it had to be limited to Florida. He thought demonstrating statistics to prove Gore’s win could sway enough of the George W. Bush electors to switch their votes since they were not legally bound.

The Wall Street Journal first reported that Gore’s team “has been checking into the background of Republican electors with an eye toward persuading a handful of them to vote for Mr. Gore.”

Beckel insisted afterward he never had plans to try to blackmail electors to collect Gore votes, which he thought the article implied. But in an interview on Fox News on Nov. 17, 2000, Beckel said: “I’m trying to kidnap electors. Whatever it takes.” Beckel later explained what the Founders wanted: “The idea was that electors, early on, were to be lobbied.”

Pro-Gore websites even started popping up, listing the names and contact information of Republican electors across the country, asking the public to barrage them with demands to vote for Gore and follow the will of the people.

Republican National Committee Chairman Jim Nichols sent an email to supporters asking them to “Help Stop Democratic Electoral Tampering.” Responding to the chairman, Beckel said: “The Constitution gives me the right to send a piece of mail to an elector.”

It never made a difference. No electors shifted, but it did serve as another twist as the 2000 election story unfolded—and another PR fumble for Democrats.