As courts over the last few weeks dealt a series of blows to voter identification laws in states across the country, Indiana’s Secretary of State Connie Lawson was feeling fortunate.

More than a decade ago, before it was the rage to do so, Lawson, then a Republican state legislator, co-sponsored a bill in the name of preserving election integrity that requires Indiana voters to produce photo identification to vote.

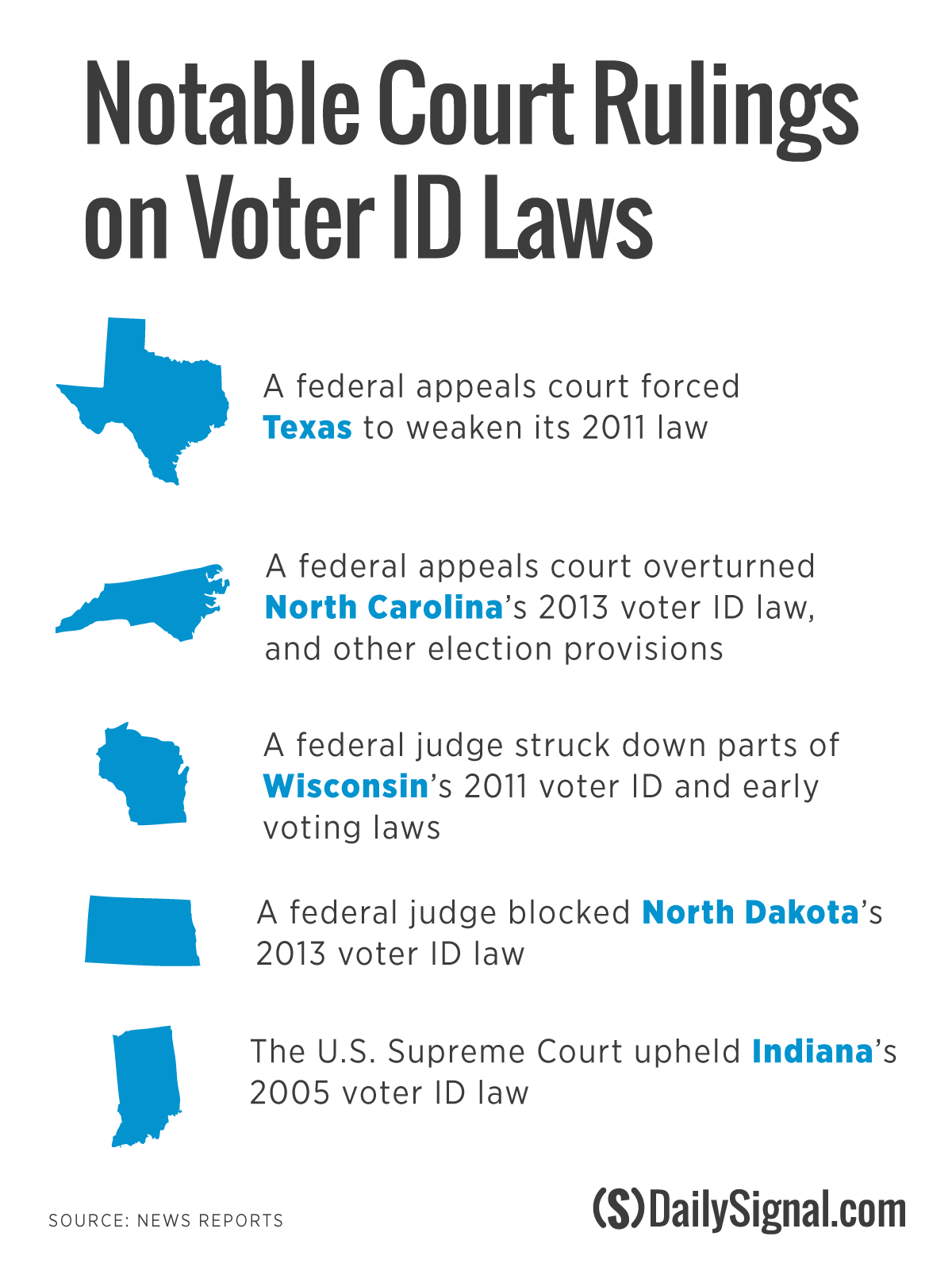

Three years after the legislation became law in 2005, the Supreme Court upheld it as constitutional, and today, Lawson, as the state’s chief elections official, is describing Indiana’s photo identification law as a success story. She says it’s a triumph that states discouraged by recent court rulings should learn from.

The Daily Signal depends on the support of readers like you. Donate now

“When we wrote the legislation, we did everything we could do to make elections honest and make sure everyone can participate in the election process,” Lawson told The Daily Signal in an interview. “So we added protections [against disenfranchisement] that maybe some of the other laws don’t have. And now, our law has stood the test of time. It passed the test with the U.S. Supreme Court, and it’s been in place for over a decade now.”

Lawson says that turnout for presidential elections has increased since the law’s implementation—it jumped from 58 percent in 2004 to 62 percent in 2008, a year when President Barack Obama became the first Democrat to carry Indiana since 1964. Turnout fell back to 58 percent in 2012.

And she contends there is “no compelling evidence” to prove voters are being blocked from the ballot box because of stricter identification requirements, although she says it’s “impossible to measure” whether the law has prevented a case of in-person voter fraud.

The courts are making their own declarations on voter identification laws.

On July 20, a federal appeals court ruled Texas’ 2011 voter identification law violated the 1965 Voting Rights Act by discriminating against black and Latino voters. On Wednesday, Texas, responding to the court’s request to adjust the law, agreed to expand the types of identification required to vote.

Last week, a federal appeals panel went further and overturned North Carolina’s more sweeping 2013 voter identification law, which included other measures such as shortening the early voting period and banning same-day registration.

That same day, a U.S. district judge struck down several parts of Wisconsin’s 2011 voter identification law, in addition to other election laws passed by Republican state lawmakers. And on Monday, a federal judge blocked a 2013 voter identification law in North Dakota, ruling that it harmed Native Americans in the state.

While Lawson is using these court rulings against voter identification laws as an opportunity to share what she considers to be Indiana’s successes, opponents of her law say they are emboldened to try and get rid of it again.

“What’s happening now is courts are starting to look at these laws and asking the very valid question of whether they are disenfranchising more voters than the number of people who are stopped from engaging in voter impersonation fraud,” said Bill Groth, an Indianapolis attorney who represented Democratic lawmakers in their Supreme Court challenge to the state’s voter identification law.

“If we can find the right group of plaintiffs to challenge the Indiana law anew, I would feel much better undertaking that lawsuit in light of recent legal developments,” Groth told The Daily Signal in an interview. “There is nothing I would enjoy more than to see the Indiana law struck down or more workarounds be mandated so that it doesn’t continue to stand as an obstacle to people who want to participate in the democratic process.”

How Voter ID Came to Be

Indiana’s experience with a voter identification law, and how different constituencies interpret its impact, showcases the tension around an issue that touches on people’s freedoms, sense of fairness, and fears.

Since the 2000 presidential election recount in Florida, paranoia about the integrity of the U.S. election system has increased. A Pew Research Center survey found that 48 percent of Americans were confident that “the votes across the country were accurately counted” in the 2004 election.

After the 2012 election, that percentage fell to 31 percent.

Rep. Todd Rokita, R-Ind., recognized these fears and seized on them before he came to Congress and began his service as Indiana’s secretary of state. When he was elected in 2002, Rokita was 32 years old and the youngest secretary of state in the U.S. at the time, looking to make a mark.

“Back in 2001 and 2002, election integrity was a huge issue for the secretary of state,” Rokita told The Daily Signal in an interview. “It was the thing. It was the main promise I told people I would do. I look at it as a promises made promises kept situation. The problem was that people were losing confidence in the system. There was a perception that people were not taking the process seriously—there was a fear of votes being stolen. Even if the fear didn’t pan out to be true, and in some cases it wasn’t, the fear was still there.”

Rep. Todd Rokita, R-Ind., implemented one of the first voter identification laws in the country when he was Indiana’s secretary of state. (Photo: Bill Clark/CQ Roll Call/Newscom)

In 2005, Rokita, who helped write the original legislation, implemented one of the first photo identification laws in the country, and defended it before the Supreme Court.

With little precedent to work from, Rokita said he and the other authors sought to craft a “narrow law” with “reasonable” exceptions for those who can’t obtain the identification the law requires.

Rokita’s effort in Indiana was occurring at a time prior to what is considered a turning point in election laws, when the Supreme Court in 2013 struck down a section of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

That decision eliminated the requirement that the federal government approve changes in election procedures made by certain states with a history of racial discrimination.

“Maybe that’s part of our success because we approached it as a all whole cloth,” Rokita said. “We made it ourselves. We stitched it up. And that caused us to do a lot of thinking and soul searching and making sure we were balanced and honest in our approach to prove it was not politically motivated.”

What’s in a Law

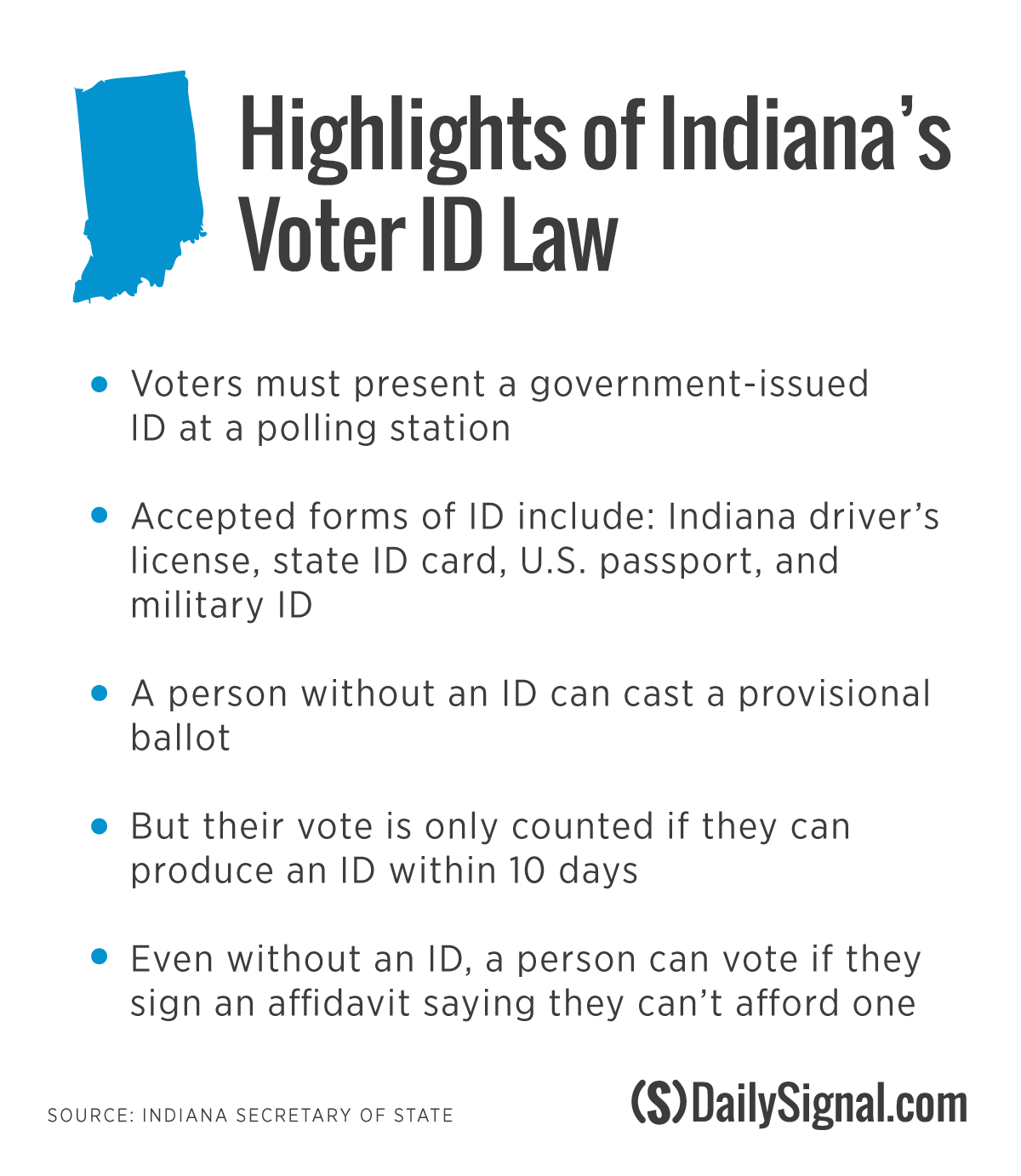

Indiana’s law, considered one of the strictest in the nation at the time, requires people present at a polling station on election day to provide a government-issued identification.

Accepted forms of identification include an Indiana driver’s license, an Indiana state ID card, and a U.S. passport. Photo identification issued by the military also qualifies. The state provides free photo identification to those who can’t afford to pay for one, but a potential voter still has to provide documentation, like a birth certificate, to prove who they are.

The law contains “workarounds,” or exceptions.

A person who comes to the polls without identification can cast a provisional ballot, but their votes are only counted if within 10 days they can produce valid identification or sign an affidavit stating they can’t afford it, or have a religious objection to being photographed. In addition, a person who is 65 years old or older, or disabled, can submit an absentee ballot through the mail without providing identification.

“What you have to pay attention to with Indiana and how it may be a little different than other laws is the Indiana law is written in such a way that it’s relatively easy to get around showing ID if you don’t have one,” said Michael J. Pitts, an Indiana University law professor and elections expert, in an interview with The Daily Signal.

Impact on Voting

Still, the plaintiffs in the Supreme Court challenge to Indiana’s law, which included the local branches of the American Civil Liberties Union and the NAACP, argued it would impose burdens on people who are old, poor, or minorities, groups that the challengers said are less likely to have the accepted types of identification.

Pitts, in the only study of its kind in the state, tried to measure if the law disenfranchised voters in the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections.

To determine this, Pitts decided to look at the number of provisional ballots cast in each election, and how many were counted.

Pitts found that in the the 2012 general election, about 650 people in an electorate of nearly 2.7 million did not have a ballot counted because of a problem with voter identification.

However, less than 10 percent of provisional ballots voters casted due to a lack of identification were ultimately counted.

Those results were enough for Pitts to declare in the study that “at the moment, there is no compelling evidence to demonstrate that the amount of actual disfranchisement [of potential voters] is in the hundreds, or even tens of thousands within Indiana.”

Meanwhile, Lawson, Indiana’s secretary of state, has her own data looking at a longer time frame. She said since the state’s 2006 primary elections, 8,614 provisional ballots have been cast, with 3,659 of those actually being counted.

In addition, she said, the state has distributed 1,866,955 free photo identifications to voters since 2005.

Despite the fact the state has not counted a majority of provisional ballots, Lawson insists “it’s not fair” to say those whose votes were not included were “disenfranchised.”

“There has not been one case where one person can name a single voter who has been disenfranchised by our voter ID requirement,” Lawson said.

But critics maintain that the process to verify a provisional ballot during the 10-day period is too burdensome for some people, and that others are choosing to stay at home because they’re intimidated by the law’s requirements.

“There are people out there hurt by this law,” said Groth, the Democratic attorney. “We know they are out there. But because they kind of operate in the shadows of life, we don’t often cross paths with them. If somebody is willing and able to navigate the obstacles, yes, they can vote, but the question is why are we imposing those obstacles on people struggling just to make ends meet and who want to participate in the electoral process.”

Impact on Fraud

Just as it’s hard to put a face to those harmed by Indiana’s voter identification law, supporters acknowledge the challenge of proving it has prevented fraud.

“Obviously I think voter fraud convictions are rare,” Lawson said.

A 2014 study by Justin Levitt looking at in-person voter fraud found there to be 31 instances out of more than 1 billion ballots cast in local, state, and national elections over 14 years.

Rokita, the former Indiana secretary of state and current congressman, admitted it’s difficult to detect acts of impersonation at polling places, but he argues there’s a reason why.

“I am not ceding the point it is rare,” Rokita said. “It’s rare because the type of crime we are talking about isn’t like a murder where there’s evidence. There isn’t a dead body. The crime happens in an instant, and all the evidence walks out the door, walks out of the voting booth or precinct hall.”

“The problem was that people were losing confidence in the system,” said @ToddRokita.

Lawson and Rokita pointed to a 2012 case when a jury convicted Charlie White, Indiana’s secretary of the state at the time, on multiple charges of voter fraud, including felony charges for false registration, voting in another precinct, submitting a false ballot, and theft.

Hans von Spakovsky, a senior legal fellow at The Heritage Foundation, said Indiana should be especially concerned about fraudulent absentee ballots that are filed through the mail.

In 2003, the Indiana Supreme Court invalidated East Chicago Mayor Rob Pastrick’s Democratic primary victory because of fraudulent absentee ballots. According to The Washington Post, 46 people, mainly city workers, were found guilty of committing absentee ballot fraud by giving their ballots to another person.

“We know from this major case that fraud does occur in the state,” von Spakovsky said. “So while it was a good first step for Indiana to enact a law addressing in-person voter fraud, I think the state should have taken a second step to extend it to safeguard against absentee voter fraud, as some states like Kansas have.”

‘Law of the Land’

Even if the impacts of Indiana’s voter identification law are disputed, elections experts say the state’s legacy in election reform will be watched closely over the coming months, as other states try to satisfy court rulings, and possibly take their challenges to the Supreme Court.

“Indiana at the time of the decision was the strictest [voter ID law] in the nation, but some of the other laws that have been struck down are even stricter,” said Joshua A. Douglas, a University of Kentucky law professor who specializes in elections. “So the courts may be saying you can go up to the severity of the Indiana law, but you can’t go farther. That may be the message from the courts in this slew of cases.”

Pitts, the Indiana University law professor, cautioned to be careful in evaluating Indiana’s law in relation to other states.

“I do worry about people trying to take broad conclusions state to state on these kinds of matters,” Pitts said. “Because all of these laws are written differently, and to some extent, Republicans were emboldened by Crawford [Indiana’s law] and thought they could do quite a bit more. They really are very individual with different legal provisions being invoked.”

As voter identification law opponents look to continue their momentum, Rokita is confident Indiana’s law will remain standing.

“The Indiana case is still very much the law of the land and I don’t expect that to change,” Rokita said.