Despite the lack of a definitive ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court on the constitutionality of mandatory union dues, workers across the nation have ample opportunity to challenge why they’re forced to pay for political activism they don’t support.

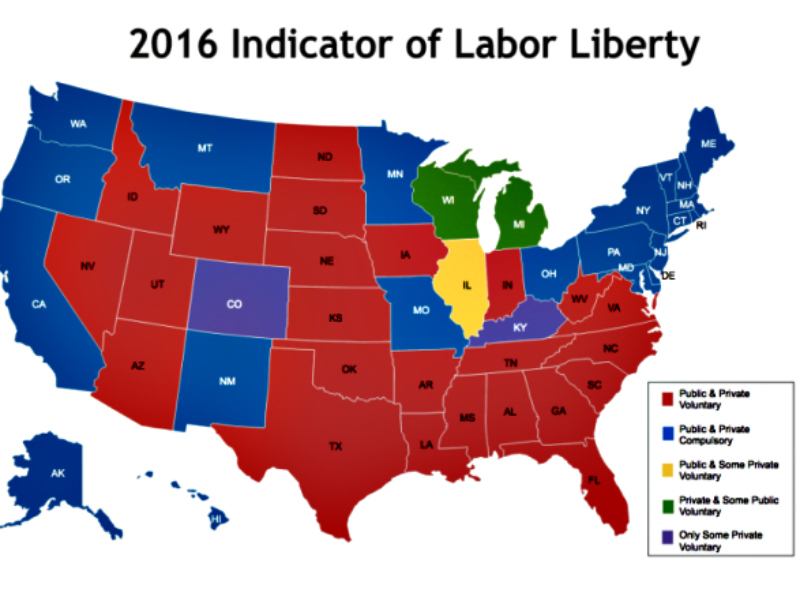

That’s clear from a state-by-state map that measures the current level of worker freedom in both the private and public sectors.

When the high court split 4-4 this week on a landmark case challenging “agency shop” rules requiring public employees to pay union fees, it meant a lower court ruling in favor of the unions will stand.

However, those who watch “right to work” issues closely say, other litigation will continue to gestate at the state and local levels.

In Illinois, for instance, the town of Lincolnshire is pressing ahead with a right-to-work ordinance that has received scant press attention, but could have significant legal reverberations.

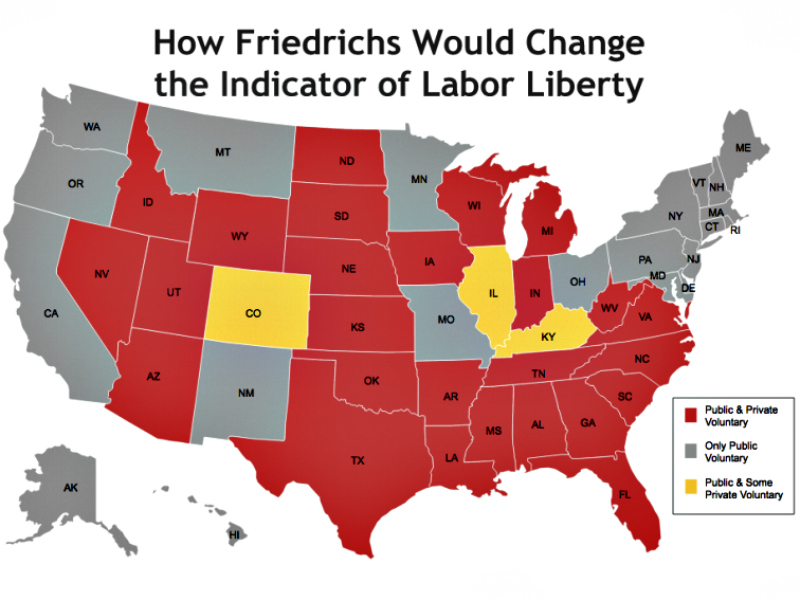

The Supreme Court case known as Friedrichs v. California Teachers involved public sector workers. But had the high court ruled in favor of 10 California schoolteachers who object to that state’s agency shop rules, it likely would have created additional momentum for right-to-work initiatives in the private sector, according to a team of researchers with the Center for Worker Freedom, a project of Americans for Tax Reform.

The court announced its 4-4 deadlock Tuesday. Rebecca Friedrichs, a 28-year veteran of the Savannah School District in Anaheim, Calif., and the lead plaintiff, has said that she and her legal team plan to file a petition for a rehearing.

“It’s unfortunate and disappointing, and everything is going to depend on who the new [Supreme Court] justice is,” James Sherk, a labor policy analyst with The Heritage Foundation, said. “But states should continue in their efforts to protect worker freedom.”

Since half of the justices on the Supreme Court were prepared to rule in favor of Friedrichs and her nine co-plaintiffs, the court’s ruling should be taken as a sign that the “notion of forcing workers to pay an advocacy organization to campaign for public policies they oppose is on shaky legal ground,” he added.

In the meantime, efforts aimed at freeing workers from forced unionization remain the subject of ongoing litigation. Already, several unions have filed suit to overturn the right-to-work ordinance in Lincolnshire, Ill.

Before the Feb. 13 death of Justice Antonin Scalia, the teachers who were the plaintiffs in Friedrichs appeared poised to secure a major victory against the unions on behalf of free speech.

For this reason, as The Daily Signal reported last month, researchers with the Center for Worker Freedom put together what they term the “2016 Indicator of Labor Liberty,” maps that show how the right-to-work landscape would look before and after a ruling in favor of the Friedrichs plaintiffs.

Right-to-work laws prohibit an employer and a union from signing a contract that would require workers to be union members. An “agency shop” like the one for California teachers requires that the workers who do not want to join the union instead pay it a fee instead of dues.

The center offers two versions of the map. One highlights the status quo of labor law across the country; the other demonstrates how government workers in 25 states would be freed from forced unionization if the high court someday were to rule mandatory dues unconstitutional.

Color schemes distinguish the states.

Red states have the most worker freedom, because a worker’s decision whether to join a union or pay union fees is voluntary in both the public and private sectors. Blue states have the least freedom, because union requirements apply to both government and non-government workers.

So, what would happen if Friedrichs and her fellow teachers were to prevail at the Supreme Court? Those blue states, which include New Mexico, California, Oregon, Washington, and states concentrated in the Northeast, would flip to the color gray to show that public sector workers in those states are free. Purple and green states also would flip to gray.

Under Challenge

With the status quo locked in place for now, the Center for Worker Freedom identified a need for greater clarification in state labor law. This is especially true in those states that have a peculiar mix of worker freedom and forced unionization, such as Kentucky, Wisconsin, Colorado, Illinois, Michigan, and Missouri.

The center adjusted its categorization of Illinois and Michigan after initial release of its “labor liberty” maps to reflect legalities particular to those states.

Sherk, the Heritage labor policy analyst, recommends that the researchers’ maps take pending litigation into consideration.

In Illinois, for example, Sherk points out that Gov. Bruce Rauner’s executive order prohibiting the exacting of “fair share” fees from state employees “is tied up in litigation and not currently in effect.”

Moreover, he says, the Republican governor’s measure doesn’t apply to local government employees such as schoolteachers.

Patterson has a different view of the situation in Illinois.

“It’s true that Governor Rauner’s executive order in Illinois is under legal challenge,” he said. “However, those legal proceedings were on hold pending a decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in Friedrichs. Now that the high court has issued a split decision, we expect the issue of public workers in Illinois to now proceed in federal District Court and above.”

More Choice in Illinois

Paige Halper, a research fellow at the Center for Worker Freedom who is project leader for the Liberty Indicator, notes that just because Rauner’s executive order isn’t being enforced, doesn’t mean it can’t be considered valid.

“Right now, the First Amendment isn’t being enforced either [in U.S. labor law],” Halper says. “But it’s still considered the law of the land.”

Ultimately, the Center for Worker Freedom chose to portray Illinois in its Liberty Indicator as “public sector voluntary,” in effect lending moral support to Rauner’s order, though Patterson concedes others take a different view.

But what about local government employees?

Patterson is not convinced they’re excluded under the executive order.

“Local jurisdictions exist at the discretion of the state government and therefore are, in a sense, extensions of it,” Patterson said. “So if it’s unconstitutional for state labor authorities to force state workers to pay union fees, as the governor argues, it follows that it’s also unconstitutional to make local employees pay the fees.”

The Center for Worker Freedom altered its color category for Illinois in response to a local right-to-work initiative in that state.

“The town of Lincolnshire recently passed a local right-to-work ordinance, similar to what was done in Kentucky,” Patterson said. “And even though it is under legal challenge, we changed Illinois on our map to yellow to reflect the fact that some private workers now have a choice.”

Rebecca Friedrichs, a California schoolteacher challenging union dominance, speaks with reporters Jan. 11 outside the Supreme Court after her case was heard. (Photo: Jeff Malet/SIPA/Newscom)

Michigan and Missouri

The situation in Michigan also presents complications.

“Michigan’s right-to-work law, like Wisconsin’s, only covers some government employees,” Sherk told the Daily Signal in an email. “It does not apply to police or firefighters.”

The Center for Worker Freedom, after consulting with Sherk, changed Michigan’s color on its map to green, reflecting the fact that some public workers—police officers and firefighters—currently are forced to pay the union. But even here, Patterson said, it need not be the case:

In our view, the Michigan Supreme Court’s decision [upholding the state’s public sector right-to-work law] begs the question why some workers are forced to pay and others not. If it is unconstitutional for some, it’s easy to see a policeman or firefighter questioning the constitutionality of his or her own forced dues.

As for Missouri, and whether its public sector workers are forced to pay the unions, Halper’s research found no statute or legislation indicating freedom to opt out for the state’s public workers.

“We called several government agencies, including the state’s Department of Labor,” Halper told the Daily Signal. “We were told that the issue is decided on a case-by-case basis between unions and employers. Because in theory that means that any public worker in Missouri can be forced to pay, we decided to leave the state blue [meaning compulsory union fees for public and private workers] for the time being.”

‘A Catalyst’

Luke Hilgemann, CEO of Americans for Prosperity, said he views the “Labor Liberty” maps as a call to action on a front where his organization already leads the charge. Hilgemann said:

We have engaged in a comprehensive citizen education campaign to let people know about their rights. Even though 26 states have passed right-to-work [laws], it is up to groups like ours to go out and educate citizens about their rights. When the laws change they are not going to get the straight story from the union representation. I think that’s where we come in since there are a lot of misconceptions that are spread around by organized labor.

Four years ago, Americans for Prosperity organized a town hall event in Waukesha, Wis., to inform average citizens about their rights under existing labor law. Hilgemann sees the gathering as a prototype for what might come.

“Worker freedom can be a catalyst for reform down the road,” he said. “Once you get organized labor out of the way, it clears the slate for other free market ideas to start taking hold.”