The 2015 year in crime was marked by a sharp rise in murder rates in many U.S. cities, including those touched by high-profile incidents between police and citizens, such as Baltimore and Chicago.

But the rate of crime overall in America’s largest cities declined in 2015 (as of Dec. 23) compared to the year before, to a level half of what it was in 1990.

This contrast, while not abnormal, has criminologists split on its significance heading into a new year, when attention to police-community interactions, and the broader criminal justice system, promises to be especially intense.

Many in Congress are hoping early this year to act on legislation to reduce prison sentences for nonviolent drug offenders.

“The policy takeaway is that there is not a national crime or murder wave, so if people are still pursuing criminal justice reforms, they should be able to do so without thinking there is evidence of a debilitating crime wave,” said Inimai Chettiar, referencing a report she oversaw conducted by the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law.

In October testimony to Congress, however, FBI Director James Comey urged caution after the increase in murders.

“This is worrisome,” Comey said, “and it drives us to be even more thoughtful about how we change our criminal justice system.”

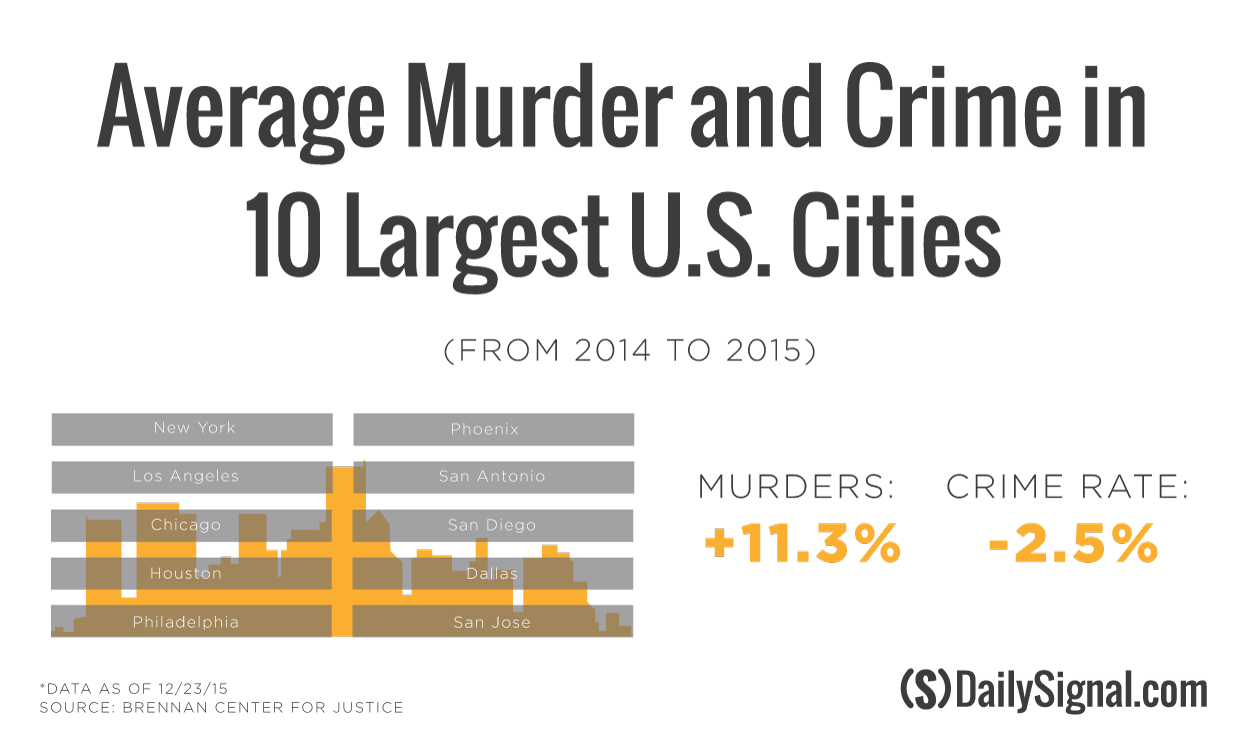

The Brennan report found that in the 10 largest U.S. cities, crime rates as of Dec. 23 were on track to decline by 2.5 percent from 2014 levels, while murder rates were expected to rise 11.3 percent.

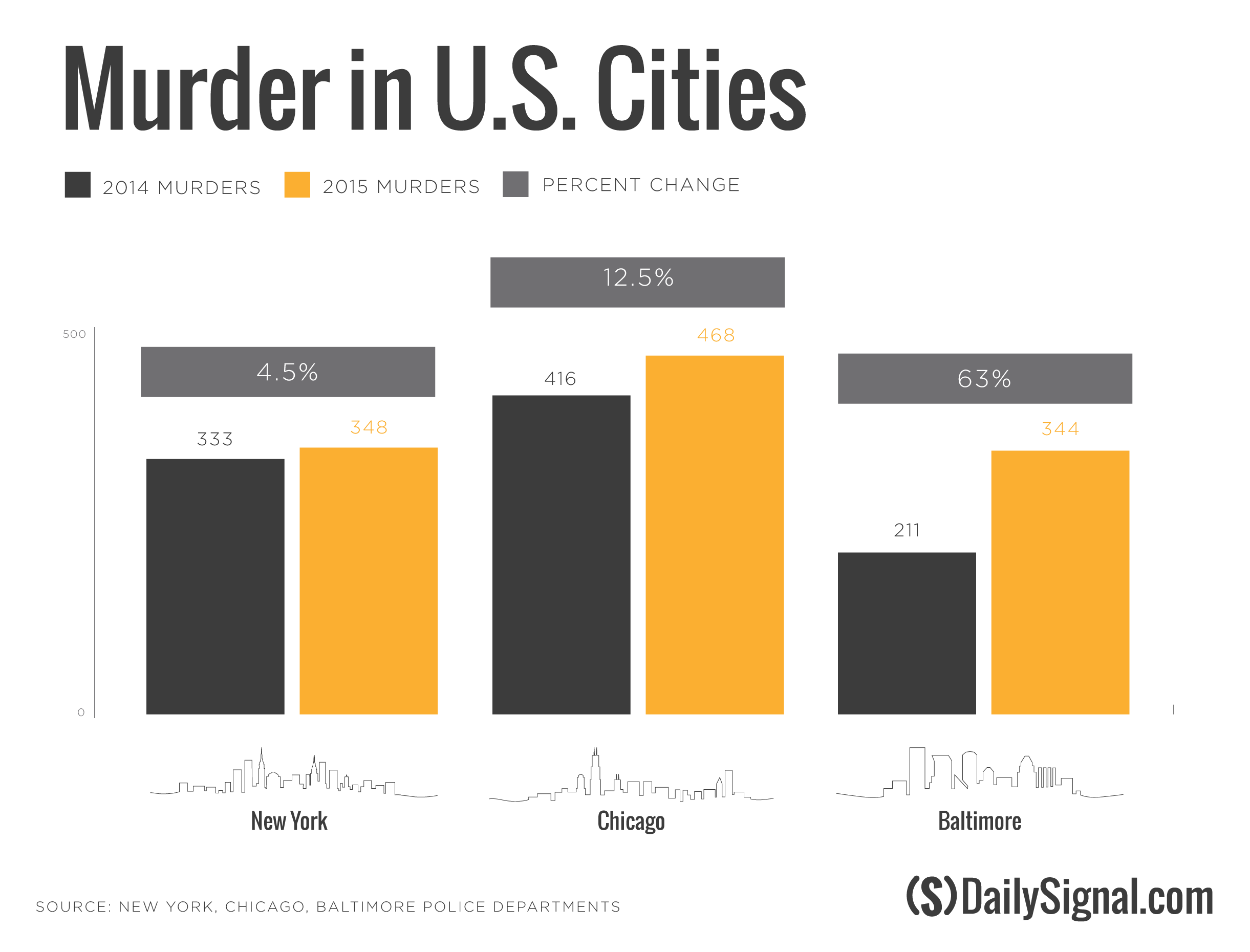

Washington, D.C., and Baltimore together account for nearly half of the increase in murders nationwide.

Experts told The Daily Signal that disparate factors are behind the rising murder rates, and their contrast with the overall crime rate, although all of them caution that it will be years, if ever, before the reasons are clear.

“Some of the fluctuations you see in numbers are inexplicable,” said Ronal Serpas, who was the superintendent of the New Orleans Police Department from 2010 to 2014.

Serpas, who is now a professor at Loyola University New Orleans and the co-chair of the national group Law Enforcement Leaders to Reduce Crime and Incarceration, cautions that it’s difficult to make year-to-year comparisons of homicides, and that long-term trends tell a fuller story.

Though it is too early to say what caused the sudden rise in murders last year, criminologists are watching to see what happens in 2016, as national attention on use of force by police requires departments to reckon with how to keep communities safe while also respecting citizens.

Baltimore: Deadliest Year Ever

After experiencing its deadliest year ever on a per capita basis, Baltimore is already grappling with this challenge.

The vast majority of the city’s 344 homicides were black-on-black crimes involving gunfire, according to the Baltimore Sun.

The number of homicides rose significantly after the April death of Freddie Gray and subsequent riots against police that captured the nation’s attention.

>>>Will Freddie Gray’s Death Inspire ‘New Life’ to Baltimore?

The Sun reported that the city averaged more than a killing per day since Gray’s death while in police custody.

Some critics claim that Baltimore’s rise in homicides and decline in arrests after the Gray tragedy showcase the so-called “Ferguson effect theory.”

This theory holds that the criticisms of police following the shooting death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., influenced cops to be more cautious with how they do their jobs for fear of being punished.

“We’ve had the Ferguson case, Baltimore, Chicago, and the broader ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement, and some cities in the middle of that had really bad years with respect to violence,” said John Roman, a senior fellow at Urban Institute. “The hypothesis is that this has caused violence to increase in places where police are nervous about policing. I think at the end of the day, it’s hard to believe that’s not true in some part.”

Serpas, the former police superintendent in New Orleans, who has also served as police chief in Nashville and Washington state, dismisses the Ferguson effect theory.

“I don’t see any evidence that officers are rolling up in a fetal position and afraid to do their jobs,” Serpas said. “Are there some police and departments that feel way? You can’t exclude that possibility. But the concept that police are being watched by the public did not explode in 2015. It’s a bit insulting to say the business of policing would stop because police are being observed by the public, because that’s what we’ve been dealing with since we started 200 years ago.”

Officers ‘Not Deterred’

To make his point, Serpas says the advent of dash cam video cameras on police vehicles occurred during his career as police chief. But more recently, police departments are adopting body-worn cameras for officers, and citizens have become emboldened to capture interactions with police on their phones.

In an interview with The Daily Signal, T.J. Smith, the director of media relations for the Baltimore Police Department, rejected the idea that the department’s officers are reluctant to enforce the law.

“Our officers are not deterred—absolutely not,” Smith said. “They are still putting themselves in harm’s way, and many officers get offended, given that some people are saying they are deterred.”

The president of the Baltimore police union, meanwhile, has said that some officers have reported being afraid to do their jobs since six of their peers were charged in Gray’s death.

Still, Smith called the city’s 2015 murder rate an “anomaly,” noting that killings were on pace with recent years in the early months of the year before the unrest in April.

Gun Violence

Smith does not tie the sudden rise in murders to outrage over Gray’s death.

Instead, like other cities such as Chicago, which had the most homicides of all U.S. cities in 2015, Smith says that police are finding more illegal weapons with high-capacity magazines.

Baltimore’s officers seized 30 percent more illegal guns than last year. The Baltimore Sun reports that gun violence, including nonfatal shootings, increased more than 75 percent in the city compared to last year, with more than 900 people shot. More than 2,900 people were shot in Chicago in 2015.

Jeffrey Ian Ross, a University of Baltimore criminologist, says most gun violence today is related to drugs and gang activity.

“Almost all of it is connected to drugs and gangs,” Ross said. “It’s control of territory, markets, competition inside gangs for leadership control and also among rivals, keeping them at bay. I think that’s what we’re seeing in most cities experiencing an increase in murder and violent crime.”

Likewise, Richard Rosenfeld, a University of Missouri-St.Louis criminologist, believes that drugs are driving violent crime, specifically over heightened demand for heroin.

“I am convinced some of the increase [in homicides] is due to drug market expansion, and we have to hope, like the crack-cocaine epidemic, this is short-lived,” Rosenfeld said. “On the drug user side, it’s clear there’s a need for more treatment. On the violent crime supply side, it’s not clear to me what police can do that they’re not already doing.”

Criminal justice reform proposals in Congress would allow low- or medium-risk offenders to earn time off their prison sentences if they participate in drug rehabilitation programs.

Engaging the Community

Smith of the Baltimore Police says the department is taking action to stem violent crime.

The department is working with federal law enforcement agencies to go after gun traffickers, and the new Baltimore Police Commissioner, Kevin Davis, has said he wants the legislature to make possession of an illegal firearm a felony.

To engage more closely with the community, Smith says the department is launching a “history of Baltimore” program this year, where officers beginning with the police academy will take part in a curriculum to learn about the city’s churches, neighborhoods, and other offerings.

Similarly, starting with police recruits, Smith says the department will pair officers with a community member “to learn how literally to walk and talk and engage in conversation” with a specific neighborhood.

“We are confident in the direction we’re heading with building community relations,” Smith said. “Just doing foot patrol is not enough. It’s doing foot patrol that is not tactical in nature, where we’re just out and have a conversation with the community.”

By improving training, holding police accountable and bolstering trust with the community, the hope is that witnesses to crimes will report what they see so prosecutors can bring charges against a suspect.

The Sun reports that Baltimore has closed barely 30 percent of its homicide cases from 2015.

“There are some parts of the country ruined by drugs and crime where they need a proactive police force,” said Serpas, the former police chief. “But the ultimate goal for police should be their guardian role, which I have always believed in.”

Serpas explained:

It’s getting officers to recognize the power of explaining to the public why they are doing what they are doing, which leaves the impression they are honest and fair. That leads to public behavior change, people policing themselves, and deferring to police judgement. If you tip the scales to more community policing principles, you will have a more willing public.