In the aftermath of the San Bernardino terrorist attack, a debate has emerged over how social media should be used in the vetting of foreigners who wish to visit or immigrate to the U.S.

FBI Director James Comey confirmed this week that the husband-and-wife attackers were “showing signs in their communication of their joint commitment to jihad and to martyrdom” through private messages.

The private vs. public distinction is important, because Comey’s comments contradicted an earlier New York Times report that the female attacker, Tashfeen Malik, had talked “openly on social media” about violent jihad before entering the U.S. on a “fiancé” visa.

Subsequent media reports raised questions about the government’s commitment to reviewing social media in its vetting of visa applicants, igniting questions and proposed action by congressional lawmakers, who wondered aloud how online postings could escape notice in an age of the cyber-inspired terrorism threat.

As the facts have become more clear, the Department of Homeland Security has asserted that it has launched pilot programs to analyze some social media, but that review of private communications is limited by legal concerns. Obama administration officials have said it missed no “data points” that would’ve prevented Malik from entering the country with the intent to marry her husband, Syed Farook.

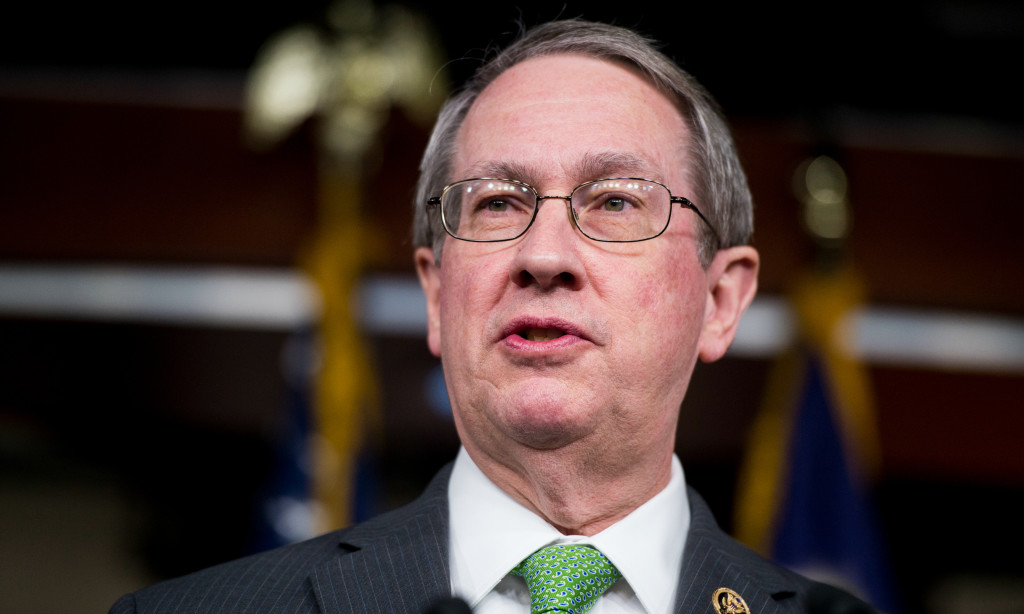

House Judiciary Committee Chairman Bob Goodlatte, whose panel is drafting legislation requiring social media checks for any foreigner applying to enter the U.S., told The Daily Signal that Homeland Security’s efforts should have few limits.

“This is not something for a pilot program,” Goodlatte said in a sit-down interview in his office. “This is something for now, which is why we are doing legislation now. So we think to the extent that the law permits it—certainly if it’s public—social media should be examined.”

“So in the San Bernardino case, the claim now is the communications were private,” Goodlatte added. “But she [Malik] was not a citizen of the U.S. So it raises the concern that the preference here was not on finding out as much as possible about someone coming into the U.S. But the preference instead was on, well, we better not ask questions, because we don’t know whether it’s appropriate or not.”

House Judiciary Committee Chairman Bob Goodlatte is proposing legislation that would require vetting of immigrants’ online statements. (Photo: Bill Clark/CQ Roll Call/Newscom)

Goodlatte, R-Va., is especially sensitive to the civil liberties vs. security debate. He is one of the authors of a recently implemented program imposed by Congress that replaced the NSA’s bulk collection of Americans’ phone records. Goodlatte says he stands by that program, called the USA Freedom Act, and he says the same balance he considered in helping write that legislation should apply in the debate over immigration and social media.

“They should have a much more robust understanding of what can be done and a very clear policy with regard to gathering all the information that they legally can gather,” Goodlatte said.

“That’s why we have asked the DHS secretary to clarify the basis of his assertion, because we believe there are plenty of circumstances when you can and should look at private communications of someone who is not a U.S. citizen and is seeking the permission of the U.S. government to enter the country.”

In addition to the concern expressed by Goodlatte, two dozen Senate Democrats sent a letter this week to Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson calling on his agency to require social media background checks as part of the visa screening process.

The concern about reviewing social media during the visa application process comes from an ABC News report that Johnson had decided to maintain a policy that prevents Homeland Security officials from reviewing the social media accounts of visa applicants.

Homeland Security officials denied the truth of that report during a House Judiciary Committee hearing on Thursday.

“What we have been doing is in fact piloting and developing the capacity to use social media in a thoughtful and functional manner,” said León Rodríguez, director of Citizenship and Immigration Services at the Department of Homeland Security. “I am not aware of there ever having been a policy that prohibited the use of social media.”

While acknowledging that foreigners are not granted the same legal protections as U.S. citizens, Rodríguez seconded an assertion by Johnson that there are limits to dealing with private communications, even by non-Americans.

“I am not sure I accept the premise we are safeguarding the rights of foreign nationals to a greater deal, but there are legal concerns,” Rodríguez said.

Rodríguez added that Homeland Security officials were still evaluating the benefit of reviewing social media, saying that “there is less screening value than you would expect in some of the early samples.”

“We are autopsying the situation to see what lessons are learned,” Rodríguez said. “Social media is clearly something we need to be talking about and something we’ve been looking to build.”

Paul Rosenzweig, a former deputy assistant secretary for policy at the Department of Homeland Security, shared with The Daily Signal some of the challenges for government officials looking to obtain the private communications of foreigners.

Rosenzweig, who is a visiting fellow at The Heritage Foundation, said the government would need permission from a court to review private messages—even on social media.

If the government had reason to question whether a foreigner had posted something suspicious on social media, Rosenzweig said the government would likely have to subpoena the particular platform where the communication occurred, such as Facebook.

Another limiting factor, Rosenzweig said, is that the U.S. has trade agreements with certain countries that govern how they exchange information with each other.

“This is about understanding that you can have a high level of national security and a high level of freedom of civil liberties at the same time,” says @RepGoodlatte.

“To review private communications is not as easy as just saying, ‘Go do it,’” Rosenzweig said.

As the Obama administration conducts a review of its visa screening processes, and Congress looks to work with them, Goodlatte insisted that officials could find a happy place.

“This is about understanding that you can have a high level of national security and a high level of freedom of civil liberties at the same time,” Goodlatte said. “When one sacrifices one for another, they are making a big mistake.”