PARIS—The National Front, a far-right French political party with financial backing from Moscow, won the first round of France’s regional elections, taking the lead in six of France’s 13 regions and reaping 28 percent of the overall vote.

The anti-EU, anti-immigration party’s electoral breakout upheaved France’s political order, and its success Sunday was not universally well received.

The following day, National Front campaign posters along Boulevard Saint Germain in central Paris were in tatters. Some were torn down. Others were covered in graffiti, including devil’s horns drawn on candidates’ heads in black marker.

One vandalized poster was yards away from a newsstand. Within the stacks of periodicals and newspapers on sale was the Dec. 3 issue of the weekly news magazine Le Point. The title of the cover story was “Putin. Our New Friend.”

The reference was to Russian President Vladimir Putin. The article, citing the terrorist attacks in Paris that killed 130, read:

Since Nov. 13, Putin is almost France’s best friend. Ukraine? The unconditional support for [Syrian dictator] Bashar al-Assad? Anti-European rhetoric? Elysée forgot about all of that in the name of the war against terrorism[.] … The war against Daesh has reshuffled the deck.

Daesh is a pejorative Arabic acronym for the Islamic State, also called ISIS or ISIL.

Some political analysts argue that the attacks also reshuffled the deck on domestic French politics, again to Russia’s benefit.

The National Front’s campaign platform taps into French Euroskepticism as well as voter anxieties about the Syrian refugee crisis and radical Islamic terrorism. Polling suggested that the terrorist attacks in Paris boosted the party’s support.

And although the National Front is a purely French creation, it has received financial backing from Moscow. Its leader is a declared ally of Putin as well as an apologist for the Kremlin’s military intervention in Ukraine.

“Moscow has a double reason to be satisfied with the terrorist attacks in Paris,” Marcel Van Herpen, director of the Cicero Foundation, a Dutch think tank, told The Daily Signal.

“It made the National Front the biggest party of France, and it completely changed the attitude of the French government vis-à-vis Moscow,” he said.

Russian Mouthpiece?

The National Front has been a longtime outlier in French politics, best known for the Nazi-sympathizing, anti-immigrant missives of its founder, Jean-Marie Le Pen.

The party has grown steadily in popularity for several years, propelled by fears of terrorism linked to Muslim immigration and a gathering anti-EU movement that has flourished across Europe due to financial crises such as the Greek debt bailout.

In 2014, the National Front won mayoral elections in 12 cities and finished first with about 25 percent of the vote for France’s European Parliament election, taking 24 of France’s 74 seats. It was the first nationwide election victory since the party’s founding in 1973.

The National Front overturned the French political order almost overnight Sunday, proving itself to be a viable third political party and legitimizing the 2017 presidential ambitions of its current leader and daughter to the party’s patriarch, 47-year-old Marine Le Pen. (The elder Le Pen was kicked out of the party in August, sparking a family feud in which he “disowned” his daughter.)

As National Front’s leader, Le Pen has made several trips to Moscow to meet with government officials, including a meeting with Putin in February 2014, one month before Russia’s annexation of Crimea, according to the French investigative news site Mediapart.

In March 2014, Russian officials invited Le Pen to Crimea to observe the Ukrainian peninsula’s referendum to join the Russian Federation, which since has been discredited by the EU and the United States as illegitimate. Le Pen turned down the offer, sending her foreign affairs adviser at the time, Aymeric Chauprade, in her place.

Le Pen, however, later supported Russia’s takeover of Crimea and criticized U.S. policy on Ukraine. In an interview with the Polish news site Do Rzeczy, she said, “Regarding Ukraine, we behave like American lackeys,” adding that “the aim of the Americans is to start a war in Europe to push NATO to the Russian border.”

Intercepted text messages released by the hacker group Anonymous International and published by Mediapart in April were said to prove that a Kremlin official wanted to reward Le Pen for supporting Russian policy in Ukraine.

In November 2014, Le Pen admitted that the National Front had received a 9-million-euro ($9.8-million) loan from the Russian-owned First Czech-Russian Bank. French news reports claimed it was the first installment of a request that was four times larger.

She subsequently pushed back against accusations that the Moscow-financed loan was a reward, arguing it was “ridiculous to suggest that gaining a loan would determine our international position.”

“The Front National acts today with Putin’s Russia the way the French Communist Party did with the USSR: a party under control of a foreign power,” Edmond Huet, a French engineer and arms expert, told The Daily Signal.

Huet assisted the Ukrainian government in identifying the weapons used against protesters in Kyiv during the 2014 Ukrainian revolution.

He said of the French Communist Party: “PCF was ideologically Moscow’s mouthpiece and opinion relay in France. Front National does the same for both ideological reasons, real or not, and financial reasons.”

Utilitarianism

The National Front’s success Sunday spooked France’s political establishment, spurring an unprecedented proposal by French President François Hollande’s Socialist Party to ally with the center-right opposition party, Les Républicains, in regions where the National Front leads voting.

Les Républicains, under the leadership of former French President Nicolas Sarkozy, rejected the offer. Spurned by their longtime foes and willing to defeat the National Front at all costs, the Socialists subsequently urged some of their candidates to withdraw from the race, hoping to divert votes to Républicain contenders.

The 2017 presidential elections are dictating much of the political maneuvering in the days ahead. Sarkozy, who is expected to run in 2017, declared his position as “neither merger, nor retreat,” implying that any cooperation with Socialists to defeat the National Front is unlikely for the time being.

Euroskeptic, anti-immigration parties like the National Front are on the rise across Europe. Russia has loaned money to many of them, including Greece’s neo-Nazi Golden Dawn, Belgium’s Vlaams Belang, Italy’s Northern League, Hungary’s Jobbik, and the Freedom Party of Austria.

Some analysts argue that the Kremlin is maneuvering to weaken the EU and NATO and diminish U.S. influence on the continent.

Van Herpen argues that that by financing the National Front, the Kremlin is pursuing four of its key foreign policy goals:

In the first place, an overt anti-EU policy. In the second place, an anti-American policy. In the third place, an anti-NATO policy, which follows from the second. In the fourth place, the attempt to forge a tripartite Moscow-Berlin-Paris axis. In particular, the last goal is interesting, because such an axis would realize all the other goals; it would undermine the EU, NATO, and the transatlantic relationship.

Anton Shekhovtsov, visiting senior fellow at the British Legatum Institute think tank, echoed Van Herpen’s analysis in a May 2 article for The Interpreter. Shekhovtsov wrote:

The scope of the cooperation between the French far right and the Russian authorities, which started long before the annexation of Crimea, indicates that it is one of the many elements, albeit a significant one, of the Kremlin’s long-term strategy to support all the anti-EU and anti-U.S. forces in Europe in order to undermine the transatlantic cooperation and ultimately weaken the West.

Rapprochement

Tensions over Ukraine have strained the Franco-Russian relationship.

In August, Hollande canceled the sale of two Mistral warships to Russia due to sanctions over the Ukraine war and pressure from Washington. The cancelation was a blow to the Kremlin—Russian sailors were already in the French port city of Saint-Nazaire for training, and port facilities were under construction in Vladivostok.

According to Defense News, France negotiated a settlement to repay the 893 million euros ($981 million) in cash Russia paid in advance for the warships,which Egypt later purchased.

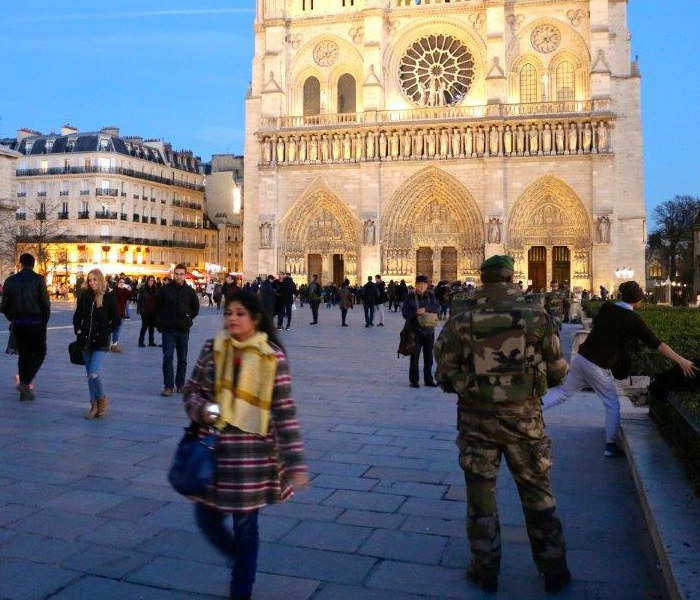

Ultimately, Hollande’s differences with Putin over Ukraine took a back seat to the war on the Islamic State, or ISIS, after the terrorist attacks in Paris. On Nov. 26, the French president flew to Moscow to ask for Putin’s help in fighting the Islamist terrorist army. Hollande’s entreaty was part of a broader effort to unite Russia’s military efforts with those of France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the U.S.

Yet Franco-Russian rapprochement isn’t limited to the National Front or Hollande’s post-Nov. 13 diplomatic trade-offs. A delegation of 10 French MPs—nine from Sarkozy’s center-right Républicains—visited Crimea in July under a Kremlin invitation to gauge whether citizens there were happy with joining the Russian Federation.

The French entourage lauded Russia’s takeover of Crimea, claiming that the Ukrainian peninsula was “happy to be back in Russia.”

A media firestorm ensued in France (and in Ukraine), highlighting a quietly growing pro-Russian bloc among mainstream French conservative leaders. Even Sarkozy, who famously said he would “rather shake [George W.] Bush’s hand than meet with Putin,” apparently has warmed to the Russian leader, making a controversial visit to Putin’s Moscow residence in October.

“Isolating Russia makes no sense. … We need to choose rapprochement and dialogue,” Sarkozy told a group of Russian students during the trip, Agence France-Presse reported.

It is not clear how popular this rapprochement will be with French voters. An August poll by the Pew Research Center found that 70 percent of French respondents had an “unfavorable” opinion of Russia. And 85 percent had “no confidence” that Putin would “do the right thing regarding world affairs.”

“The National Front program, if implemented—exit of Euro, exit of EU, exit of NATO—would be a total victory for Putin and the last nails in France’s coffin, the loss of hope for recovery,” Huet said.

The front lines of the Ukraine war also reflect the complicated diversity of French opinions about Russia. Former French special operations troops and former French foreign legionnaires have fought on opposite sides of the war, joining the ranks of pro-Ukrainian volunteer battalions as well as pro-Russian separatist units.

“I came here to fight Russia,” a French special operations soldier fighting with the pro-Ukrainian Azov Battalion told The Daily Signal during an interview in Kyiv in June. He spoke on condition of anonymity due to security concerns.

“It’s abominable what Russia has done here,” he said. “You can’t just invade another country. That’s not how Europe works anymore.”