In their lists of demands for the $1.- trillion omnibus spending bill, Republican lawmakers and leaders of conservative groups are calling on House and Senate leadership to stymie the federal government’s ability to use taxpayer dollars to pay insurance companies through Obamacare’s risk corridor program.

But what exactly is the risk corridor program, and how does it work?

Implemented under the health care law and in effect until 2017, the risk corridor program is one of the “three Rs”—alongside risk adjustment and reinsurance—designed to provide protections for insurers and spread the potential risk some may encounter by insuring more unhealthy patients than in the past.

The program’s goal is to limit excess losses and gains incurred by insurance companies selling plans on the federal and state-run exchanges. Insurers that profit each year above a certain threshold pay into the program, while those that lose money receive payments from the federal government.

The crafters of the Affordable Care Act modeled the risk corridor program after a plan set up under Medicare Part D prescription drug coverage, and though the programs differ, they both seek to accomplish the same goal of spreading out the risk for insurers.

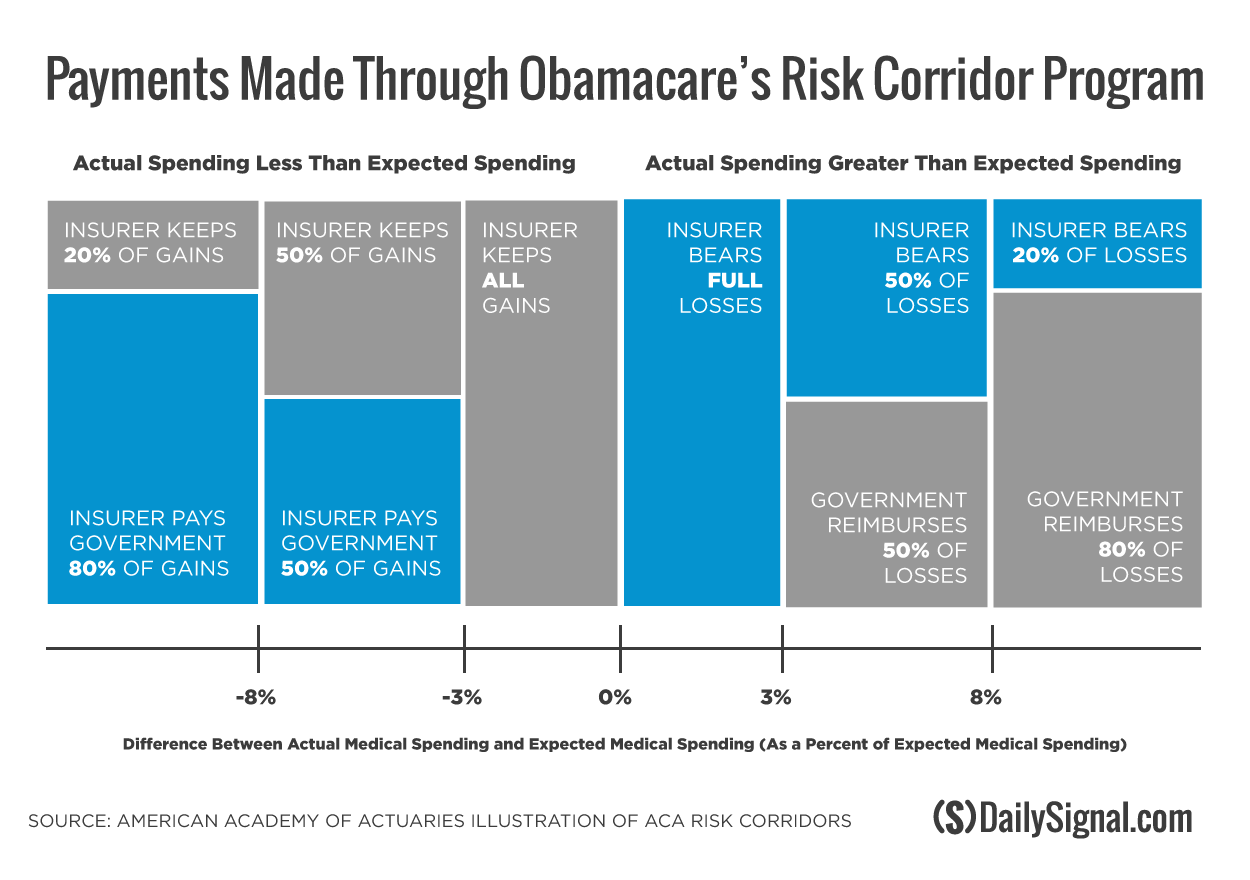

Under the risk corridor program, insurance companies selling plans on the exchanges determine the actual cost of claims compared to their expected cost of claims, which are reflected in premium prices. And that difference determines whether an insurer will share some of its profits with the federal government or receive money from the government.

According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, if an insurer’s actual claims are within 3 percent of its expected claims, the insurer will either keep the profits or bear the full losses.

However, if an insurer’s actual claims are more than 3 percent of its expected claims, the federal government will reimburse the company for at least half of what it lost.

By contrast, if an insurer’s actual claims are less than expected plans by more than 3 percent, the insurer pays the Department of Health and Human Services at least half of the excess profits.

In the event that the federal government fails to collect enough from profitable insurers to cover others’ losses, the taxpayers will be forced the cover the difference.

Though the program implemented under Medicare Part D has been called successful, Republican lawmakers, led by Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., have criticized Obamacare’s risk corridor program, calling it a taxpayer-funded “bailout” for insurance companies.

Since 2013, Rubio has been working to limit the use of taxpayer dollars for the risk corridor program, first by introducing legislation to repeal the Obamacare provision that established and administered it.

Though Rubio’s bill stalled in the Senate, Republicans negotiated a policy rider included in a must-pass government spending bill last year that limited the amount of money available for the program. Under the measure, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services was prohibited from using taxpayer dollars for the risk corridor program and instead had to rely solely on fees collected from the insurance companies themselves.

In October, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced it took in just $362 million from profitable insurers. Insurance companies that lost money, meanwhile, requested $2.87 billion.

Because the government received far less from successful insurers than what was requested by those who were less profitable in 2014, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services informed insurers they would receive 12.6 percent of their requested risk corridor payments.

Rubio is still working to repeal the risk corridor program and introduced legislation in the Senate once again doing so. Additionally, he and conservative House members are calling on House and Senate leadership to limit the use of taxpayer dollars for the risk corridor program in this year’s omnibus spending bill, which Congress has until Dec. 11 to pass.