The disputed policing tactic that enables law enforcement to seize property from people who were never convicted, or often even charged, with a crime is on the rise across the U.S., according to a report released Tuesday.

The Institute for Justice found that despite heightened public awareness of the practice, called civil asset forfeiture, government seizures are continuing to grow at a rapid pace, varying in degree from state to state.

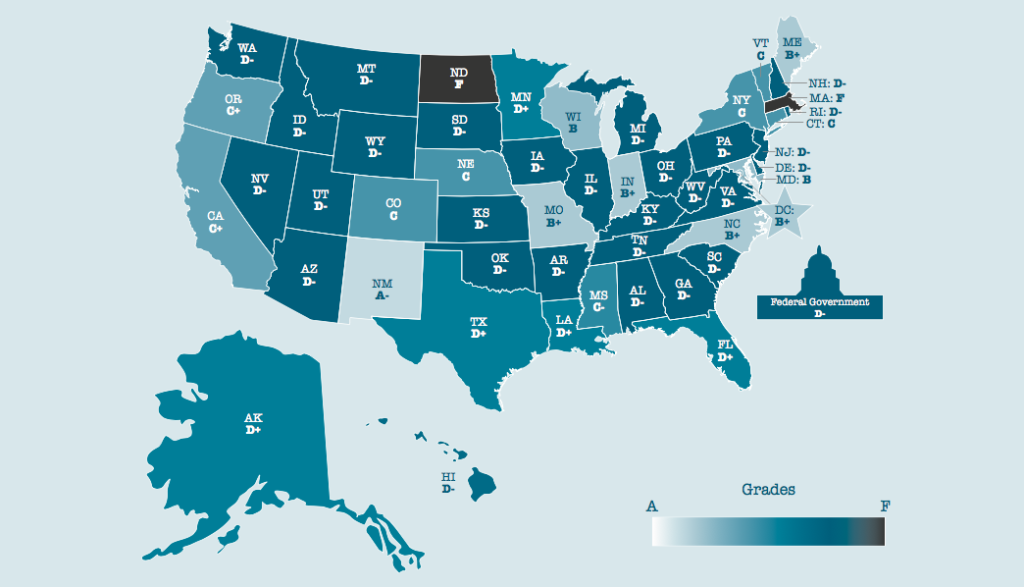

In its second annual “Policing for Profit” report, the institute examined nationwide forfeiture laws, assigning each state, along with Washington, D.C., and the federal government, a grade based on three criteria.

Those include the financial incentive for law enforcement to pursue forfeitures, the standard of proof the government must meet to seize property, and whether the burden to prove innocence falls on the property owners or the government.

In the Institute for Justice’s second annual “Policing for Profit” report, 35 states earned grades of a D+ or worse for their forfeiture laws while only 14 states and Washington, D.C., received grades of C or better. (Photo: Institute for Justice)

According to the analysis, 35 states earned grades of a D+ or worse, while only 14 states and D.C. received grades of C or better.

Massachusetts and North Dakota fell to the bottom of the list, earning F grades because of civil forfeiture laws providing limited property rights protections to residents in those states along with perverse incentives for law enforcement agencies to seize property.

Both states, for example, allow law enforcement agencies to keep 100 percent of the value of forfeited property, which is often then funneled into the agencies’ budgets.

Dick Carpenter, director of strategic research for the Institute for Justice and co-author of the report, said that while state reforms have occurred in recent years, law enforcement typically pushes back because of such incentives.

“Forfeiture laws do very little to protect rights of individuals,” Carpenter told The Daily Signal. “They instead create processes that make it easier for law enforcement to seize and forfeit, and they make it extremely difficult for property owners to get their properties back once their properties are seized.”

He pointed to New Mexico, which received the highest grade of an A-, as a model for other states to follow.

This past year, the state ended civil forfeiture and replaced it with criminal forfeiture laws, requiring that the government first convict a property owner in criminal court before any property may be seized.

Further, the new law eliminated financial incentives for law enforcement agencies to seize property by prohibiting forfeiture money from funneling into agency accounts. Any money captured through forfeiture instead has to be deposited into the state’s general fund.

But Carpenter said despite sweeping changes in some states, too few are currently considering reforms.