Citizens of the small East African country of Burundi are at the polls today to select a president, though the outcome is virtually guaranteed.

Two-term incumbent President Pierre Nkurunziza is expected to glide to a third term, particularly since the opposition has announced it will be boycotting the vote.

At issue for the opposition is Nkurunziza’s decision to run for a third term, despite article 96 of the country’s constitution that allows a president to be elected for two terms only. Furthermore, the Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement for Burundi, which brought an end in 2005 to a brutal civil war that ripped the country apart, forbids in Article 7.3 a president from serving for more than two terms.

Nkurunziza is bound by Burundi’s constitution to be the “guarantor of the national independence, of the integrity of the territory and of the respect for the international treaties and agreements.” He also in March promised U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon he would respect the Arusha Agreement and constitution, though he has since ignored his obligations to the former.

Whether Nkurunziza is violating the constitution is a murkier issue. He claims another five years as president should be considered only a second term, as he was elected to his first term by the parliament, and not by “universal direct suffrage” as stipulated in the constitution.

Burundi’s constitutional court agreed with Nkrunziza’s interpretation in a ruling in early May. The court’s vice president, however, fled the country shortly before the ruling was announced and claimed that the court had been intimidated into finding in Nkurunziza’s favor.

Whatever the truth of the constitutional matter, President Nkurunziza should not have run again. His decision has touched off a wave of demonstrations that has led to the deaths of 70 people, mostly protesters, thus far. Another 500 have been injured, and more than 140,000 have fled to neighboring countries. One of the leaders of a May 13 failed coup, General Godefroid Niyombare, now claims to be raising a rebel army to unseat Nkurunziza. The country is edging toward war.

The violence has primarily been political in nature, but it runs the risk of reopening old ethnic wounds in a country with a tragic history. Since independence from colonial Belgium in 1962, tension between the majority Hutu and minority Tutsi has routinely flared into bloodletting, including two genocides. Precise numbers are elusive, but in all approximately 600,000 Burundians have died in internal violence since independence.

There is another danger as well. Hutu and Tutsi can be found in several neighboring countries such as Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo. In 1994, Rwanda suffered one of history’s worst genocides when Hutu militias killed approximately 800,000 people, mostly Tutsi. An ethnic conflagration in Burundi risks raising tensions among those communities.

It is clear too that truly free and fair elections cannot be held under current conditions.

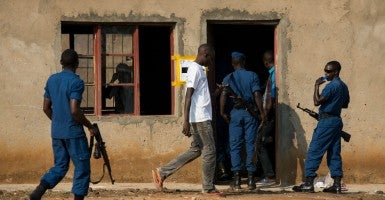

Burundian authorities shuttered several opposition radio stations in April that have not been allowed to reopen, leaving only the state-run radio station on air. Security services have arrested opposition human rights activists and killed protesters in the streets. The ruling party’s youth wing, the Imbonerakure (“those who see far”), is armed and active throughout the country, and many refugees claim they have fled the country in fear of it. The environment of fear and intimidation permeating parts of Burundi will not allow many to cast their vote freely.

The United States is concerned by the instability but has already expended most of its leverage with little effect. In May, it threatened travel bans and sanctions against anyone involved in promoting violence, and a short time later, it halted peacekeeping training for Burundi’s armed forces. The U.S., along with a number of other countries, has withdrawn its election monitoring teams, and the State Department has condemned Nkurunziza’s actions in a series of statements.

Yet Nkurunziza is determined to claim a third term—which he will do easily—so U.S. policymakers need now to focus on crafting contingency plans.

The first priority must be quickly ending any further violence, particularly before it has a chance to spread. The U.S. should encourage and support the efforts of the East African Community, a regional bloc of which Burundi is a part, as well as those of the African Union, a pan-African community, to respond quickly to a violent outbreak.

Longer-term, the U.S. will have to find ways of expressing its disapproval for Nkurunziza’s actions. Rulers across the continent are maneuvering to extend their terms at the expense of institutions and constitutions, and they are watching closely to see how the U.S. reacts to Nkurunziza.

Burundi is a poor country whose people need continued help. It also provides a significant contingent of troops to the coalition battling the Somali terrorist organization al-Shabaab, a group the U.S. badly wants defeated.

Policymakers should be working even now to craft a strategy for Burundi that balances these competing interests. Failure will mean greater instability in a fragile region, suffering for the Burundian people, and a defeat for the cause of democracy on the continent.