New student orientations are kicking off at colleges across the country, and parents are busy buying mini fridges and dorm-sized bed sheets. As students head off this fall, many will also carry with them record-high levels of student loan debt.

This year, outstanding student loan balances reached an all-time high of $1.12 trillion – an increase of $124 billion since last year, according to the New York Federal Reserve. Nearly 11 percent of aggregate student loan debt was at least 90 days delinquent or in default, as Politico reported last week

College graduates now leave school with an average of $26,500 in student loan debt – $4,600 more than the average student graduated with in 2001. Federal subsidies now account for 71 percent of all student aid. According to the College Board, over the past 10 years, the number of students borrowing through federal student loans increased by 69 percent.

The Daily Signal depends on the support of readers like you. Donate now

>>> Chart: How Student Loan Debt Has Increased in Recent Years

Increases in debt have been driven by increases in college costs. In the last 30 years, inflation-adjusted tuition and fees at private colleges increased by 153 percent. Tuition and fees at public universities for in-state students increased 231 percent.

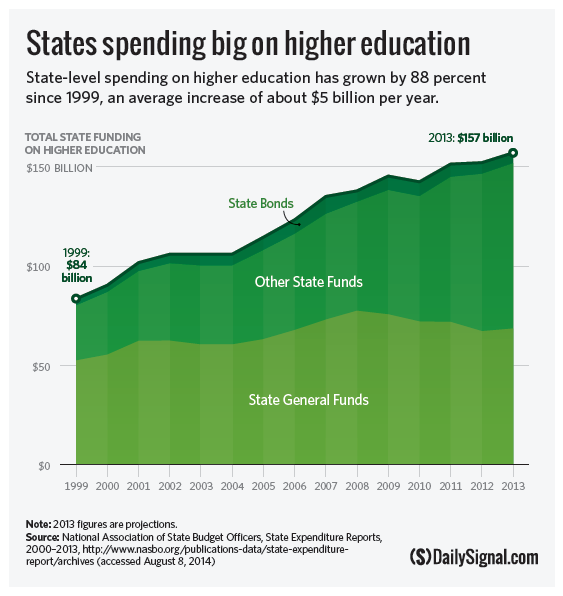

College costs have risen more than health care costs—by some estimates, twice as much—and faster than increases in the price of food. State-level spending has increased 88 percent since 1999.

Increases in tuition and fees over the past 30 years suggest that growth in federal subsidies such as loans and grants has done little to mitigate the college cost problem. And all of this spending and debt is not producing adequate outcomes:

- The 6-year college graduation rate stands at 59 percent. Just 41 percent of undergraduates complete college within 4 years.

- According to the Center for College Affordability and Productivity, 48 percent of working college graduates held jobs that did not require a college degree in 2010. Thirty-seven percent were in jobs that only required a high school diploma.

Why is college so expensive? Maybe it’s the administrative bloat. As University of Arkansas professor Jay P. Greene found, “Between1993 and 2007, the number of full-time administrators per 100 students at America’s leading universities grew by 39 percent, while the number of employees engaged in teaching, research or service only grew by 18 percent.” Student enrollment, by contrast, grew just 15 percent over the same time period.

Perhaps it’s all the college football coaches making more than $1 million. Here’s a handy list of the top ten highest paid college football coaches, compiled by USA Today. Alabama’s Nick Saban tops the list, taking home over $5.5 million in 2013.

The most likely culprit, however, is the open spigot of federal student aid that has enabled such profligacy. According to a new report from the Center for College Affordability and Productivity, federal student aid “contributes to skyrocketing costs, finances a wasteful academic arms race, weakens academic standards, lowers educational opportunity, and worsens the underemployment/overinvestment problem.”

Congress has long tried to help students afford a college education. It has cut interest rates on federal student loans, vastly expanded federal lending and lifted caps on borrowing. In the 1980s, it even let parents borrow directly from the feds — through the Parent PLUS program — to pay for their children’s college. Each effort has only enabled universities to continue to raise tuition.

Innovative approaches to limiting federal intervention in higher education through accreditation reform hold the promise of dramatically reducing college costs. Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, and Rep. Ron DeSantis, R-Fla., have put forward proposals that would do just that. By enabling states to take the lead on accreditation, the HERO Act creates a promising way to drive down costs and increase customization and opportunity in higher education.