Economist Nouriel Roubini warned late last month at the World Economic Forum that economic growth in the so-called BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) is at risk: Their past successes were “hyped up,” and the futures of the BRICs are at risk due to rising statism.

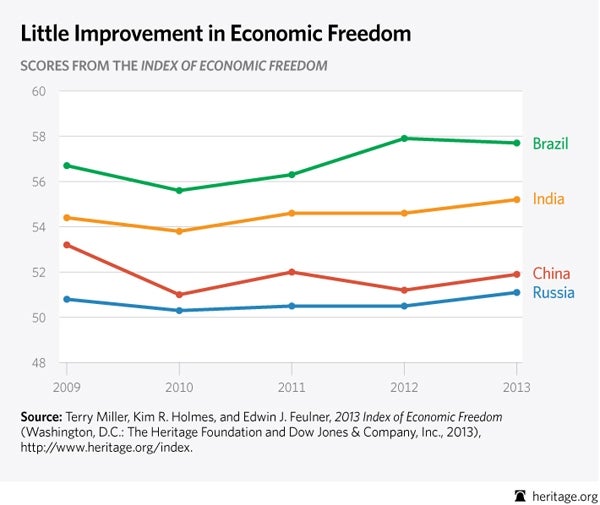

This rising risk can be seen in the graph below—stagnating economic freedom scores of the BRICs in The Heritage Foundation/Wall Street Journal’s annual Index of Economic Freedom.

As Roubini notes, the “biggest developing nations risk overturning the achievements of the past decade by increasing the state’s role in the economy.” He reported that the BRICs have recently been moving away from market economies due to increased resource nationalization, protectionism, lack of momentum for additional structural market-oriented reforms to increase the size of the private sector, and a generally larger role by the state in enterprises and banks. These specific areas of concern for Roubini are reflected in the Index scores for each of the BRICs:

- Brazil. Although Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff has agreed to privatize some companies operating highways and railways (along with, perhaps, some airports), the government still dominates too many areas of the country’s economy, undercutting development of a more vibrant private sector.

- Russia. The government of Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev has called for—but has not implemented—market reforms to reduce the role of the state in the economy. But these reforms are being stonewalled by the statist Putin presidency and state-owned industries, including oil, gas, pipelines, and the military-industrial complex, which resist transparency and privatization. Also, as Heritage’s Ariel Cohen reports, “Russian law enforcement and the court system are corrupt—and collapsing, which makes doing business in Russia doubly problematic.

- India. As Heritage reported last fall (prior to new promises by Indian politicians to shift back to market reform policies), the Indian government has been “famously ineffective and has shown signs of predatory behavior—putting revenue ahead of what is best for the country. It has acted as a barrier in bilateral economic relations, for example in agriculture trade and financial market access. More harmful actions, such as the recent introduction of retroactive taxation of multinational corporations, discourage foreign participation in the Indian economy in general.”

- China. Although China extended some private property rights to farmers in the late 1970s, which enabled sharp increases in food production and permitted the migration to the cities that backed the ensuing manufacturing expansion, advances in rural property rights since then have been minimal. This is part of the reason for sharp environmental deterioration and rural incomes falling far behind urban incomes. China is also the “world’s biggest thief” of intellectual property. Meanwhile, the “OECD considers China’s foreign-investment laws the most restrictive in the G20.” And state-owned enterprises have been making a comeback.

While the BRIC grouping itself—a dubious bond-marketing concoction by Goldman Sachs more than decade ago—is not important, the policies of large developing economies are. The warnings of the 2013 Index of Economic Freedom about stagnating economic freedom in the BRICs (and elsewhere) are very clear—and disturbing. Thankfully, the Index also includes a roadmap for the BRICs and others on how to return to the path to growth.