The government made improper payments totaling $234 billion in fiscal year 2023, about $1,800 per U.S. household, according to data released by the White House’s Office of Management and Budget.

The amount and percentage of improper payments edged down slightly from record highs during the COVID-19 pandemic. But even after subtracting pandemic unemployment insurance, the improper payment rate was 5.3% during fiscal year 2023, which ended Sept. 30.

(Note: All calculations in this analysis subtract or “net out” Defense Department compensation payments because they are distinct from other government transfer payments and employee compensation for any other department isn’t included in the data. Also, in keeping with references in the OMB reports, this analysis uses the term “improper payments” for those as figures listed by the government as “improper and unknown payments.”)

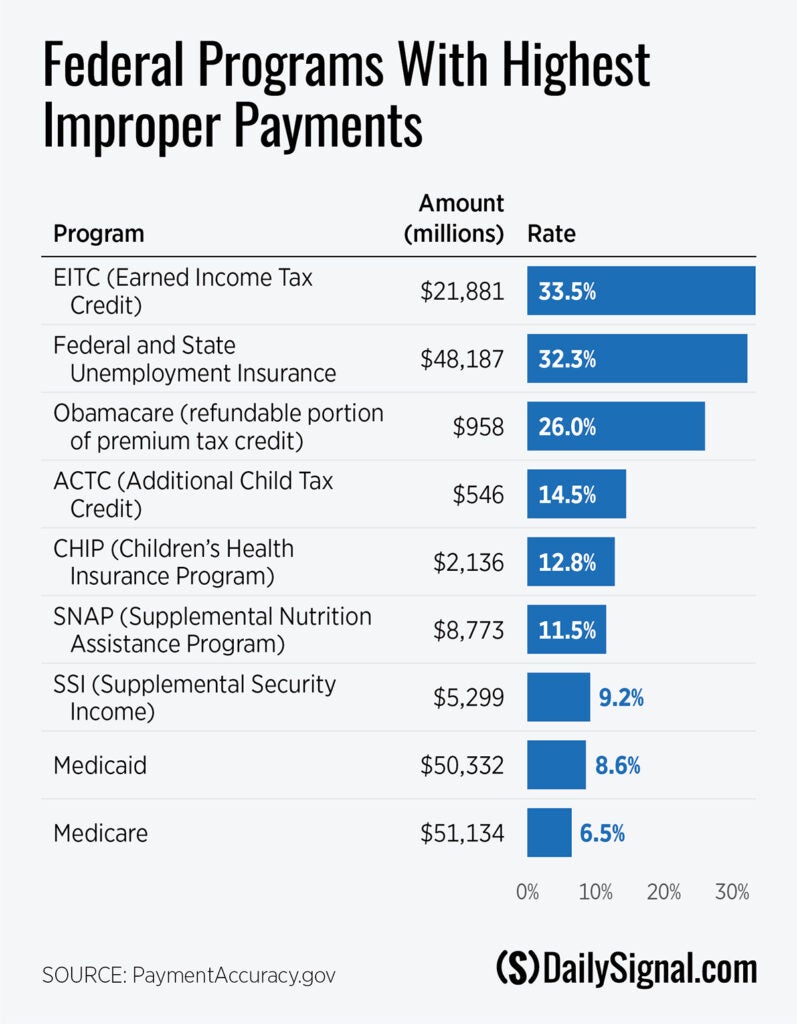

Although improper payments for most federal programs are excessively high, a few programs have extreme rates or amounts of improper payments.

Massive, and generally rising, improper payments from the government reveal a major lack of integrity and accountability in agencies’ use of taxpayers’ money. The numbers also reveal an even larger problem with an explosion of federal spending on transfer payments.

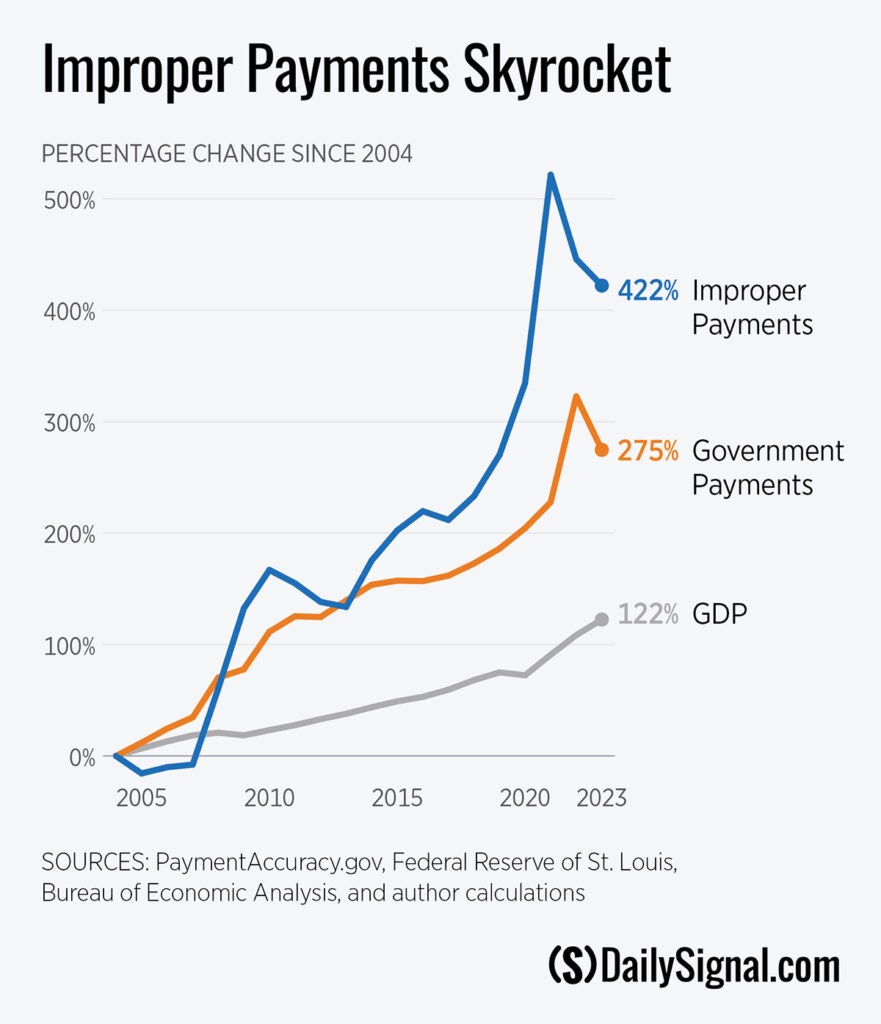

Between fiscal years 2004 and 2023, government transfers grew from $995 billion to $3.7 trillion; improper payments over those years rose from $45 billion to $234 billion.

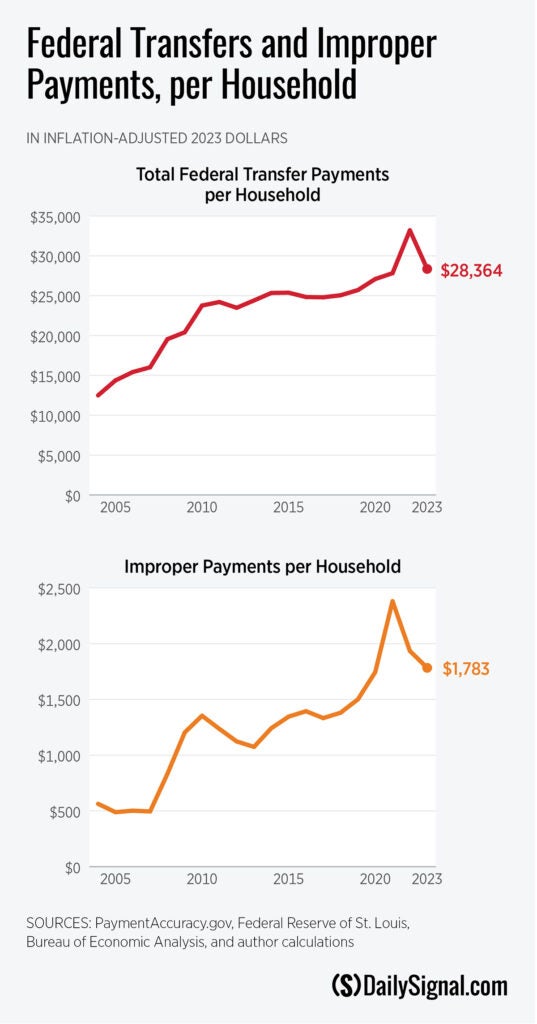

Even after adjusting for inflation and the number of U.S. households, that’s a 230% increase in government transfers, from $12,500 per household in 2004 to $28,400 in 2023.

And it’s a 320% increase in improper payments, from $560 per household in 2004 to $1,780 in 2023.

Not all improper payments are a loss to taxpayers.

For example, $12 billion of the $234 billion in improper payments in fiscal year 2023 were underpayments. And although 100% of payments sent to the wrong people are improper, only part of payments sent to the right people but in the wrong amount represent a cost to taxpayers.

Nevertheless, taxpayers have lost hundreds of billions—if not trillions—of dollars to the failure of federal government programs to issue correct payment amounts to the correct recipients.

The news media has picked up on international crime rings—including hackers sponsored by the Communist Chinese regime—that stole Americans’ identities and taxpayers’ money through the pandemic unemployment insurance programs. However, there has been little attention to and zero consequence for government programs that regularly squander taxpayers’ dollars.

Most improper payments come from failure to verify that people are who they say they are and that they’re eligible for the benefits they claim. According to this year’s Government Accountability Office report, 59% of improper payments were the result of agencies’ failure to obtain data needed to verify payments.

For example, federal agencies already are required to consult a Do Not Pay database prior to making payments, but the agencies typically ping the database, send the payments, and then receive results after the money is out the door.

Officials have used federal laws to try to crack down on improper payments by requiring agencies not only to track improper payments but to establish and carry out plans to reduce improper payments. However, nothing is done when agencies fail to meet their targets or even when their improper payments rise instead of fall.

So, any solution to reducing improper payments requires both verifying identity and eligibility as well as imposing accountability—including consequences.

To improve integrity and accountability across government programs, policymakers should consider creating a Taxpayer Integrity Office—TIO for short—within the Treasury Department.

This new Taxpayer Integrity Office should have five responsibilities:

1. Improving eligibility and ID verification.

2. Strengthening information sharing.

3. Maintaining competitive, responsive, and secure systems.

4. Establishing and enforcing reasonable standards for agencies to follow.

5. Enacting meaningful consequences for agencies’ failure, perhaps the most important responsibility.

Ensuring the integrity of government programs is crucial, but improper payments are only a symptom of the disease of excessive spending.

When the federal government expands its role into areas of Americans’ lives that are better addressed within households and businesses, by state and local governments, or through charitable and religious organizations, that’s government excess that comes at the expense of personal freedom and opportunities.

The federal government spent $3.7 trillion on transfer payments in fiscal year 2023. That’s over $28,000 per household. It’s also nearly $4 out of every $5 in taxes the government collected and $3 out of every $5 it spent.

Bigger government has meant even bigger amounts of improper payments. Since 2005, federal payments have increased at more than twice the rate of the gross domestic product; improper payments have grown three and a half times as much as GDP.

Constantly expanding entitlement programs without any consideration of what they will cost is unsustainable. Taking people’s money and requiring them to jump through bureaucratic hoops to get things the government believes people should have—like government-approved child care, government-controlled paid family leave, and government-subsidized electric vehicles—makes it harder for ordinary Americans to earn a living and pursue what they believe is best for them and their families.

To reduce improper federal spending and empower people instead of bureaucrats, policymakers should begin by replacing tax credits with lower overall tax rates, enacting universal savings accounts to make saving simpler and more accessible, and rejecting new entitlement programs while reforming existing ones.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email [email protected], and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the URL or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.