Writer-director Christopher Nolan’s summer blockbuster, the biopic “Oppenheimer,” has grossed nearly $1 billion in global ticket sales, a staggering number including over $320 million from North American theaters and over $600 million internationally.

That’s far better box office than other films Hollywood had counted on to offset the devastating, five-month strike by the Writers Guild of America and the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists.

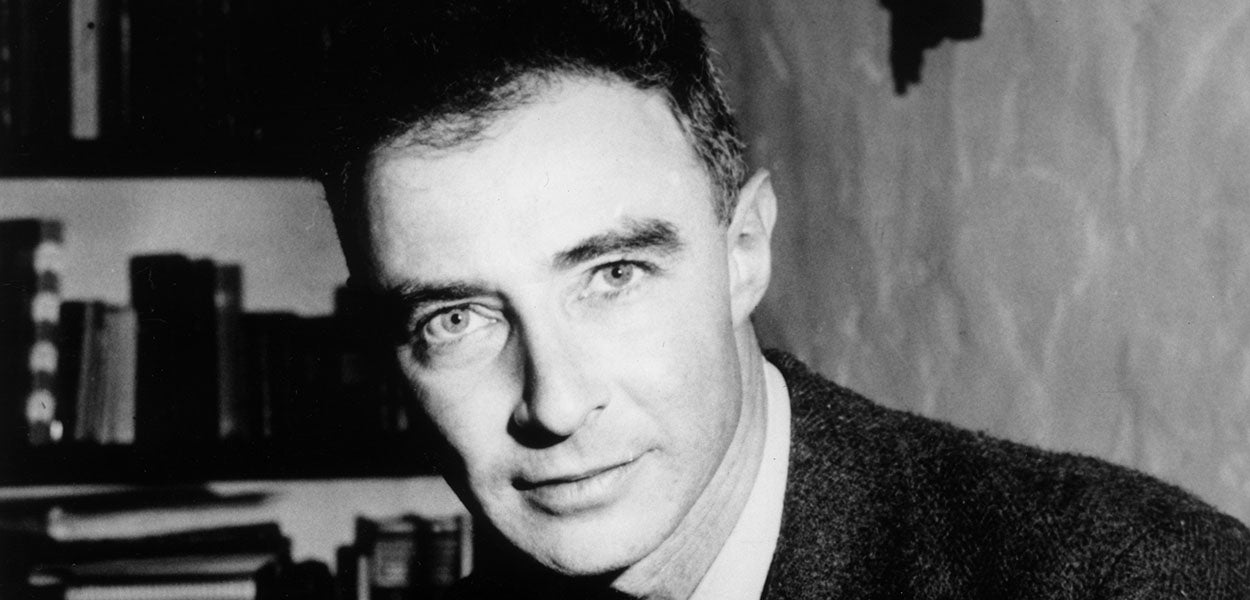

The story of the father of the atomic bomb that defeated Japan and ended World War II may well win many Academy Awards, not only for Nolan as director and writer but for lead actor Cillian Murphy as theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer and supporting actor Robert Downey Jr. as Lewis Strauss, chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission and allegedly vicious antagonist of “Oppie.”

The Daily Signal depends on the support of readers like you. Donate now

Leave it to Hollywood to falsely claim that the famed physicist was smeared by a hysterical, anticommunist community of lawmakers, federal bureaucrats, the FBI, President Dwight Eisenhower, and even Oppenheimer’s communist friends, who, in taped conversations by the bureau, repeatedly acknowledged that he was a secret Communist Party member who sided with Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin over his own country.

Those who rely on the movie for why Oppenheimer was eventually denied his security clearance will be cheated of the truth and think worse of their country for this intentional and knowingly harmful omission.

Hollywood always has been soft on communists and still refuses to acknowledge that Oppenheimer was an admirer of the Soviet Union even after it became clear that the evil empire was the deadly enemy of the United States and the West.

On Nov. 7, 1953, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover received proof that “Oppie” long had been a loyal agent of the bloody rulers in the Kremlin. The smoking gun was an explosive letter from William Borden, executive director of Congress’ Joint Atomic Energy Committee from 1949 to 1953.

The congressional staffer’s letter was prompted by the government’s compilation of a massive dossier on Oppenheimer. That dossier included, as one author later wrote, “eleven years’ minute surveillance of the scientist’s life” while his office and home were bugged, his telephone was tapped, and his mail was opened.

Oppenheimer himself was stunned and embarrassed by the revelation of his subversive conduct and repeatedly lied about it under oath.

‘Agent of the Soviet Union’

On Dec. 16, 2022, Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm, an appointee of President Joe Biden, vacated the 1954 decision to revoke Oppenheimer’s security clearance on the grounds that it didn’t properly follow some of Atomic Energy Commission procedures.

But Granholm pointedly noted that her report would not “reconsider the substantive merits” of the findings, which never have been challenged successfully.

Borden’s charges were blunt. He said that, “based upon … years of study of the available classified evidence,” Oppenheimer probably was “an agent of the Soviet Union.”

As of April 1942, the physicist “was contributing substantial monthly sums to the Communist Party” even though he publicly would deny the charge, Borden wrote. Oppenheimer’s ties to the Communist Party also had survived the “Nazi-Soviet Pact and the Soviet attack upon Finland,” he said.

Oppenheimer’s wife and younger brother “were communists,” Borden wrote in his letter, and the scientist had “at least one communist mistress” and belonged “only to communist organizations, apart from professional affiliations.”

Oppenheimer had “been instrumental in securing recruits for the Communist Party” and was in “frequent contact with Soviet espionage agents.” The physicist, Borden wrote, repeatedly gave “false information” about his Communist Party activities to Brigadier Gen. Leslie Groves, head of the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, New Mexico, best known for its central role in developing the first atomic bomb.

The FBI had opened a file on Oppenheimer as early as 1941, after he failed to inform superiors immediately that three men in Berkeley, California, had been solicited to obtain nuclear secrets for the Soviet Union and that he and his brother Frank had been urged to help them.

One colleague at the University of California at Berkeley was Haakon Chevalier, who worked with Oppenheimer on various communist enterprises and urged him to give Stalin, the Soviet premier, what he wanted.

The FBI opened its file on Oppenheimer after he participated in a meeting in December 1940 at Chevalier’s home that was also attended by the Communist Party’s California state secretary, William Schneiderman, and its treasurer, Isaac Folkoff. The FBI was wiretapping both men.

In early 1943, Chevalier and Oppenheimer had a brief conversation in Chevalier’s kitchen. Chevalier mentioned that another scientist, George Eltenton, could transmit information of a technical nature to the Soviet Union about America’s progress on the highly secretive atomic bomb project that Oppenheimer was working on.

Oppenheimer initially rejected the overture to assist Eltenton, but didn’t report the incident until six months later, in August 1943. His failure to promptly report what was clearly a Soviet espionage effort would become central to the decision to revoke Oppenheimer’s security clearance.

‘Remarkably Influential’

In subsequent interviews with Army security, Oppenheimer admitted being approached but refused to name Chevalier or anyone else who might have been involved. Not until December 1943, in response to a direct order from Groves, did he name Chevalier.

From 1937 to 1942, Oppenheimer was a member at Berkeley of what he called “a discussion group” but later was identified by fellow members Chevalier and Gordon Griffiths as a “closed” or “secret” unit of the Communist Party for Berkeley faculty.

At his hearings in 1954, Oppenheimer denied ever having been a member of the party, identifying himself instead as only a fellow traveler who had many communist friends and had given to many communist causes. As respected Oppenheimer scholars Harvey Klehr and John Earl Haynes write in the September issue of Commentary magazine, he had willingly committed perjury on numerous occasions when he “flatly denied that he had ever been a party member.”

Borden’s letter further reveals how Oppenheimer influenced U.S. military policy in multiple ways designed to weaken America and tip the nuclear scale to favor Moscow. He was “remarkably influential,” Borden wrote, in efforts “to make it difficult for us to respond militarily to growing Soviet atomic capabilities, opposing even nuclear-powered submarine and aircraft programs as well as industrial power projects.”

And this is just a small portion of an immense amount of damaging information gathered by the FBI.

Not until December 1953, however, was Oppenheimer faced with losing his security clearance. The Cold War was in full swing and Kenneth D. Nichols, general manager of the Atomic Energy Commission, had prepared a lengthy list of charges against the famed physicist designed to result in revocation of his clearance.

The chairman of the Personnel Security Board that heard the Oppenheimer case was Gordon Gray, president of the University of North Carolina. The other members of the hearing panel were Thomas Alfred Morgan, a retired industrialist, and Ward V. Evans, chairman of the chemistry department at Northwestern University. The hearings lasted through May 6, 1954, when an attorney for Oppenheimer made a closing statement.

The panel voted 2-1 to revoke Oppenheimer’s security clearance. Gray and Morgan voted in favor, Evans against.

‘Serious Disregard for … Security’

The board rendered its decision on May 27, 1954, in a sober, 15,000-word letter to Nichols, the Atomic Energy Commission’s general manager. It found that 20 of the 24 charges about Oppenheimer’s extraordinary violation of national security regulations either were true or substantially true.

The panel found that Oppenheimer’s association with Chevalier “is not the kind of thing that our security system permits on the part of one who customarily has access to information of the highest classification.” It concluded that “Oppenheimer’s continuing conduct reflects a serious disregard for the requirements of the security system.”

Oppenheimer was susceptible “to influence which could have serious implications for the security interests of the country,” the board found. Oppenheimer’s attitude toward the hydrogen bomb program also raised further doubt about whether his future participation “would be consistent with the best interests of security,” the panel ruled, and his testimony had been “less than candid in several instances.”

The majority then recommended that the physicist’s security clearance not be reinstated.

On June 12, 1954, Nichols weighed in against Oppenheimer with even more force. The AEC’s general manager bluntly stated that Oppenheimer “was a communist in every sense except that he did not carry a party card,” that the Chevalier incident indicated the physicist “is not reliable or trustworthy,” and that his misstatements might have represented criminal conduct.

Oppenheimer’s “obstruction and disregard for security” showed “a consistent disregard of a reasonable security system,” Nichols said.

On June 29, 1954, the AEC upheld the findings of the Personnel Security Board, with four commissioners voting in favor and one opposed. Eisenhower, deeply concerned about Oppenheimer’s deliberate mishandling of national security issues, ordered that a “blank wall” be placed between Oppenheimer and the nation’s atomic secrets.

Other officials with affection for Oppenheimer and his success in developing the atomic bomb also believed he should be denied security clearance.

Edward Teller, father of the hydrogen bomb opposed by Oppenheimer, testified that he believed the physicist was loyal to the United States. But, Teller added, he would like to see the country’s vital interests in hands that he could “trust more.”

Since the end of World War II in September 1945 and the emergence of the Soviet Union as America’s major enemy, Teller testified, “I would say one would be wiser not to grant clearance [to Oppenheimer].”

Convicted by Peers

Groves testified before the Atomic Energy Commission as a witness against Oppenheimer, whom he had put in charge of developing the atomic bomb. Groves reaffirmed his decision to hire Oppenheimer, since he believed his expertise and leadership abilities were instrumental to the project’s success.

But Groves also testified that under the security criteria in effect in 1954, he “would not clear Dr. Oppenheimer today.”

Oppenheimer was hardly a victim of mob justice, as Hollywood likes to suggest. He had been convicted by his peers and his friends, many of them reluctantly, after a lengthy trial.

Beyond dispute, Oppenheimer had been given every opportunity to defend himself against overwhelming evidence that he was protecting and helping to finance a foreign enemy that wished the U.S. enormous harm. Nor were those who opposed his conduct without compassion.

Nolan’s “Oppenheimer” could have acknowledged, for instance, that Strauss, as detailed by John Gizzi in a Newsmax column agreed that Oppenheimer had put national security at risk and yet found Oppie a well-paying job as the new director of the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton.

Gizzi documents how Nolan’s film markedly wrongs Strauss, who had reached the rank of rear admiral in the Navy before becoming chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission.

The movie also doesn’t note that Teller, after Oppenheimer’s loss of his security clearance, worked with President John F. Kennedy to present the controversial physicist with the prestigious and highly remunerative Enrico Fermi Award for lifetime scientific achievement.

Instead, Nolan and his Hollywood cohorts defame those who did their duty and, with malice, leave the impression that Oppenheimer was the victim of an unjust America.

This commentary originally was published by Newsmax

The Daily Signal publishes a variety of perspectives. Nothing written here is to be construed as representing the views of The Heritage Foundation.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email letters@DailySignal.com, and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the URL or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.