For decades, K-12 schools have wandered away from a time-tested, research-based method of teaching reading: phonics. Student scores have plunged to historic lows, but some states are turning back to the practice of teaching letter sounds—if teacher unions do not spoil the efforts first.

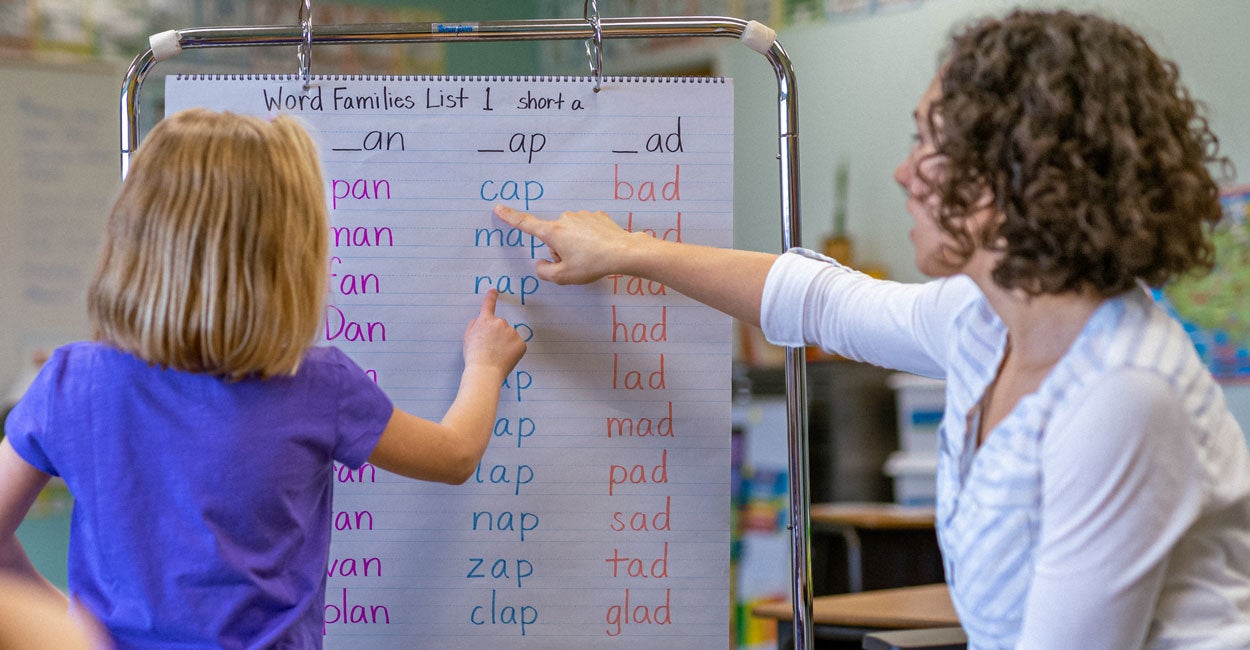

Phonics instructs children to identify letters and their pronunciation to construct words, supplying the tools needed to tackle combinations of letters. “Cueing” and its related methods, such as “look-say” and “whole word,” show children a picture with a word beneath it (such as a picture of a dog with the letters “d-o-g” beneath). Students are supposed to connect the visual with the word below. American Public Media reporter and podcaster Emily Hanford has documented the widespread failure of cueing that has haunted schools and students nationwide for generations.

In addition to Hanford’s crucial work, research finds that part of cueing’s problem is that the teacher guides given to instructors to help teach cueing do not train teachers to regularly correct students when they misidentify a word. In fact, cueing allows for students to be “close enough” sometimes—say, using “wolf” for a picture of a dog, even if the letters do not spell wolf. This imprecision is not the only problem, but researchers have identified this tendency for years, which means the technique helps explain the low scores today.

The Daily Signal depends on the support of readers like you. Donate now

One of the authors of this piece, Emma, is the daughter of an elementary school teacher who knew the value of phonics and the importance of accuracy in recognizing letters. Emma learned to read in grade school using “Junie B. Jones,” a children’s book series that follows Junie, an “almost six-year-old.” Each book began with a daily journal entry, riddled with crossed-out words with the correct spelling written above. For example, Junie might spell “vacation” as “vakatiun” which, when sounded out, would make sense to an early reader. But as the book series progresses to more advanced levels and Junie grows up in the books, these mistakes appear less often, helping readers to distinguish between correct and incorrect spellings.

These phonics-style methods have decades of research to support them. Repeatedly, research has found that phonics helps students to identify words faster and more accurately than look-say methods. As recently as 2020, research on cueing found that the method “is in direct opposition to an enormous body of settled research … that support the teaching of phonics.”

Despite the nation’s reading crisis, a 2019 Education Week study found that only 25% of grade school teachers use phonics to teach reading. Most teachers still use cueing or “whole word,” a combination of cueing and phonics that relies heavily on the former.

Teachers unions are among the most influential opponents of phonics and have advocated against the reintroduction of phonics in some states. Last year, the California Teachers Union opposed a legislative proposal that would have added phonics back to teacher training materials. State lawmakers reintroduced the proposal earlier this month, and the union remains opposed. Unions claim the California proposal “may impede [teachers’] effectiveness in the classroom.” But given the evidence in favor of phonics and California’s long history using whole word—to the detriment of students—unions are adhering to a key plank in the progressive education lexicon.

Officials in other states are already reforming their methods, with positive effects in some places. Louisiana’s Department of Education has made available teacher training materials based on what is termed the “science of reading,” a combination of strategies that includes phonics. The state has also adopted a policy that does not advance third graders if they cannot demonstrate reading proficiency.

Remarkably, Louisiana’s average reading score for fourth graders jumped 12 points from 1998, and the state moved 11 spots in the overall rankings between 2022 and 2024. These are some of the biggest gains in the entire country. Mississippi has adopted similar reforms over the last 15 years, and students there have also seen some of the biggest improvements in the nation.

The tides are changing. Despite teachers unions’ opposition, states are acknowledging the science behind reading and its effects on children’s success. For policymakers in states behind the curve, Louisiana and Mississippi provide examples to follow. On the home front, a parent’s most powerful tool is still reading to their children.