Extended periods of hot weather and drought create ideal conditions for hard-to-fight forest fires.

Although climate models predict that such weather conditions generated by human-caused global warming will increase the incidence of wildfires, recent wildfires cannot be blamed exclusively—or even primarily—on global warming: Weather-driven conditions conducive to forest fires have existed for millennia as a result of naturally occurring climate cycles.

For example, studies have shown that over the past 3,000 years, severe fires in the Western U.S. occurred during the 1800s and during the Medieval Warm Period (950–1250 AD), and some of the least destructive happened in the mid-20th century and during the Little Ice Age (1400–1700 AD).

The Daily Signal depends on the support of readers like you. Donate now

Natural climate variability clearly modified historical fire severity, but landscape changes and similar human influences—including logging and farming practices, firefighting practices, the building of railroad lines and electrical grids, domestic livestock grazing, clearing forests for farmland and settlements (including modern suburbs), deliberate agricultural burning, increased recreational use of backcountry landscapes, and the intentional or accidental introduction of weedy, non-native grasses and shrubs—have affected wildlife behavior as they have changed over time, especially since the 1800s.

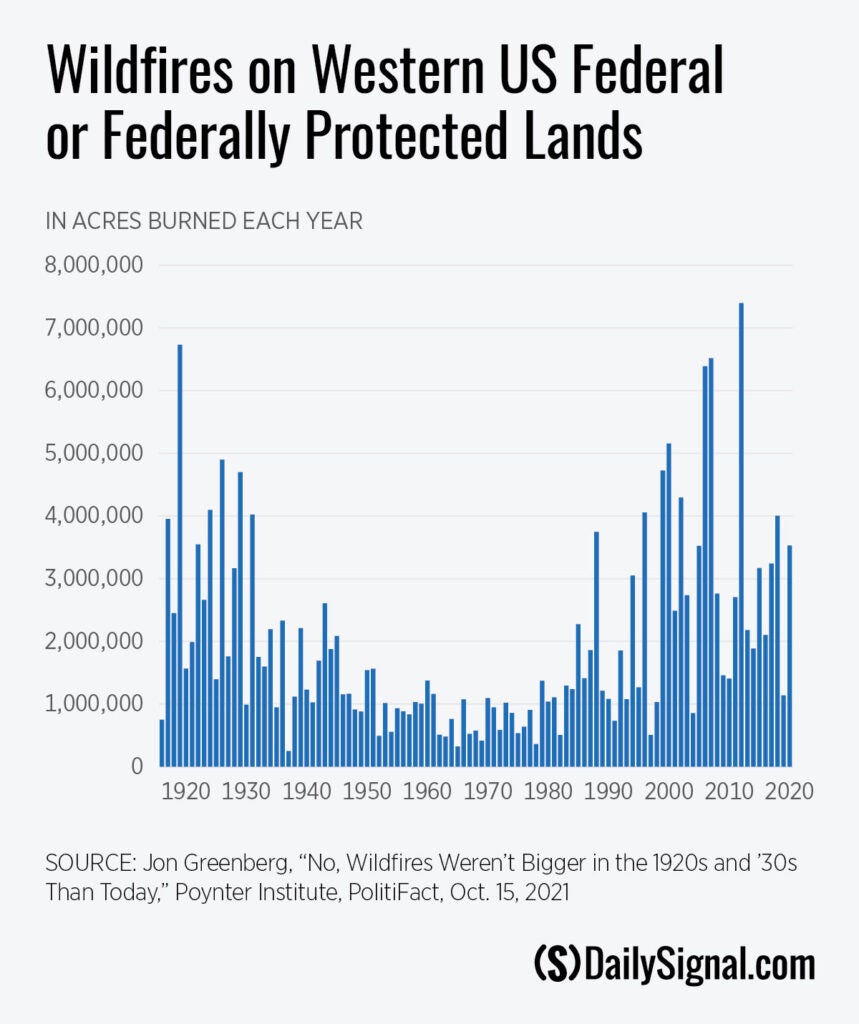

The strongest data for assessing modern forest fire severity over time in the contiguous U.S. come from the Western states (Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming), where comparable records go back to 1916.

These records show that on federal and federally protected lands, fires from 1916 to the mid-1940s (excluding those caused by arson) were similar in scale to fires in the early 2000s. The most acres burned in a given year burned in 2012, but the second-highest number burned in 1919, and some huge fires occurred before 1932 that were equal in size to more recent events.

Overall, as can be seen from the chart below, there is no obvious trend over time.

Records show that most forest fires (including arson, unattended campfires, discarded cigarettes, sparks from power lines or machinery, etc.) are started by people, whether intentionally or accidentally, and this has largely been true for hundreds of years in North America.

For example, a huge forest fire that blazed through Maine in the fall of 1825 was variously blamed on loggers burning slash piles, settlers using fire to clear farmland, and federal agents setting fire to the hay cut by illegal loggers as fodder for their draft animals, in part because such activities were known causes of forest fires at the time.

By 2021, 75% of wildfires in Oregon and Washington state were determined to be human-caused, up from the previous 10-year average of 64 percent.

Arson is a disturbing subset of human-caused wildland fires, and the deliberate intent that defines these fires can be difficult to detect and hard to prove. However, records show that arson was a serious issue in several southern U.S. states as early as the 1950s, when 35% to 50% of forest fires were judged to have been started deliberately.

More recently, one study has determined that about 86% of all fires in California since the 1990s have been caused by human activity. Other studies put that number as high as 95%, with perhaps 21% of these due to arson.

Because it takes so long for the judicial system to sort accidental fires from intentional ones, it will be years before we have any reliable data on whether arson fires have increased over the past decade. Nevertheless, research has shown that fires started by people are more ecologically destructive than naturally caused fires triggered by lightning, because they are more likely to start on open, less-forested landscapes and on very dry days with gusty winds, which increase a fire’s intensity and ability to spread quickly.

Some advocates have claimed that increased numbers of pest-killed trees caused by human-caused global warming have intensified recent fires, but it appears that purposeful changes in human behavior have been largely responsible for worsening infestations.

Recent epidemics of forest pests—including the mountain pine beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae); Western pine beetle (Dendroctonus brevicomis); spruce beetle (Dendroctonus rufipennis); and Western spruce budworm (Choristoneura feemani)—have devastated large woodland tracts across the contiguous U.S. over the past 40 years, but all of the evidence points to intentional shifts in forestry and wildfire-suppression practices as primary causal factors, and reduced timber harvests and increased fire suppression as having had the greatest impact on wildfire behavior since 1980.

Historical context is critical here, as are the often-ignored potential for other human causes and the beneficial effects of human innovation. Extreme weather conditions with devastating effect driven in part by completely natural, long-term climate cycles, short-term El Niño Southern Oscillation events, and decadal-level cycles in solar radiation—are nothing new to U.S. ecosystems.

Evidence from the Western U.S. shows that reduced logging and increased fire suppression are largely responsible for the apparent increase in wildfire severity.

Susan Crockford is a zoologist and evolutionary biologist with Pacific Identifications Inc. This essay is excerpted from her Heritage Foundation special report, “Defying Predictions: How Increased CO2 and Innovation Are Mitigating Effects of Drought on U.S. Crops and Forest Productivity,” published in November.

We publish a variety of perspectives. Nothing written here is to be construed as representing the views of The Daily Signal.