Lame ducks never make for good policy. Having passed a lame-duck vote in the House, HR 82, the so-called Social Security Fairness Act of 2023 is now set for a lame-duck Senate vote.

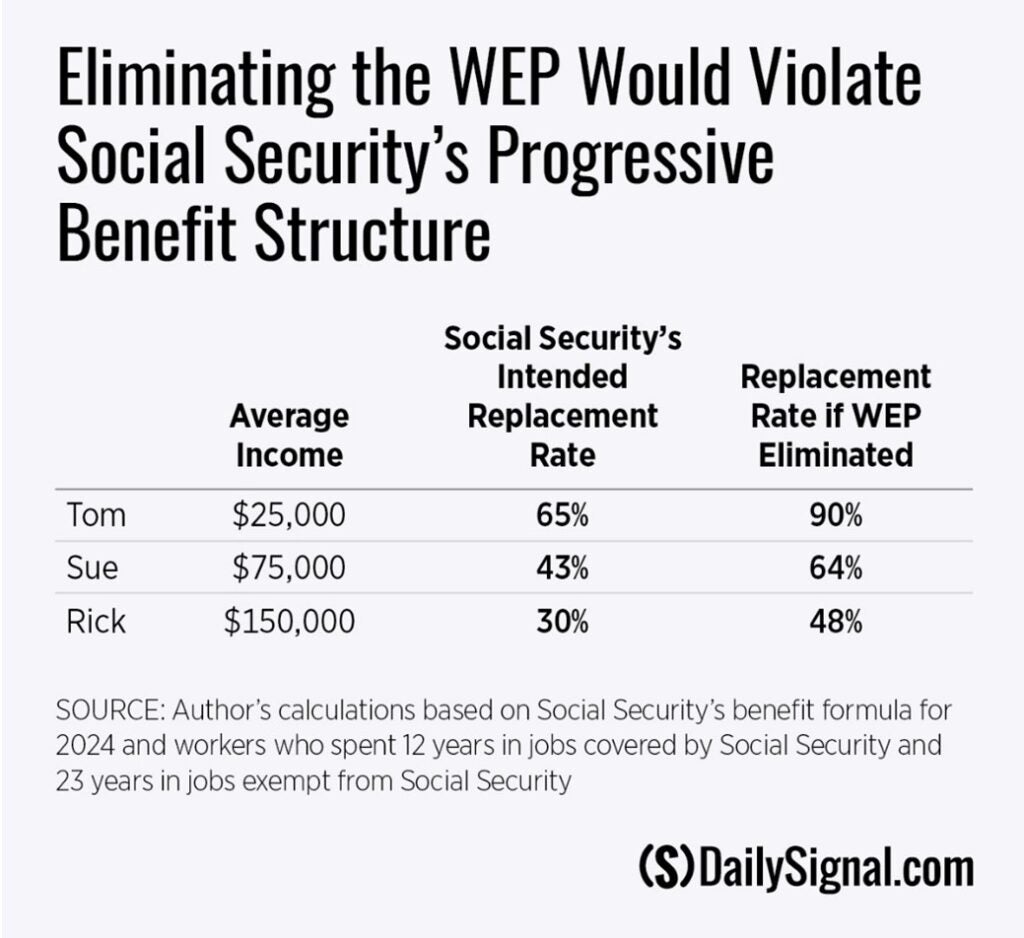

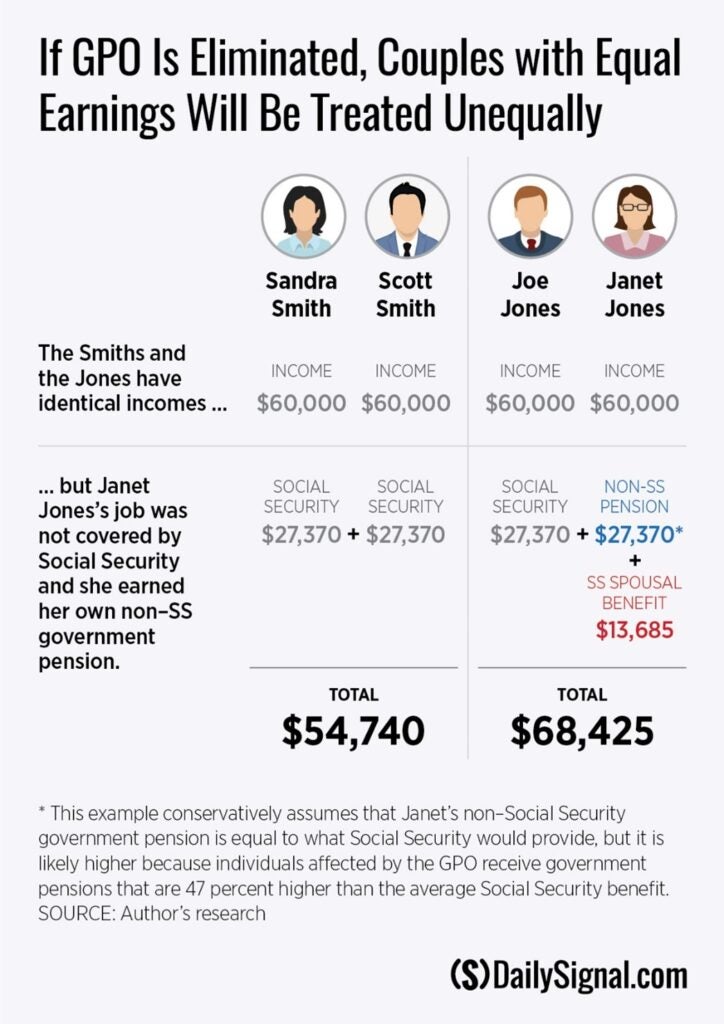

Despite its name, the Social Security Fairness Act is neither fair, nor accurate, nor fiscally responsible. It violates Social Security’s progressive nature, creates unequal benefits based on inaccurate earnings histories, and would cost Social Security $196 billion over the next 10 years. That would cause Social Security’s trust fund to become insolvent six months sooner and lead to larger benefit cuts for about 96% of all current and future Social Security beneficiaries.

The bill’s proponents say it restores benefits that they argue were unfairly taken away through the Windfall Elimination Provision, and the Government Pension Offset. Congress passed those provisions roughly 40 years ago to eliminate unintended windfall benefits, but due to a lack of data on earnings, the windfall and government pension provisions rely on ad-hoc formulas that result in some people receiving lower benefits and others higher benefits than the program intends.

While the windfall and government pension provisions are imperfect and do need to be fixed, eliminating them entirely would be fiscally reckless and unfair.

When Social Security was first enacted in 1935, people who worked in government jobs—such as teachers and public utility workers—were exempt from Social Security taxes because they paid into and received separate government pensions.

But instead of also being exempt from Social Security benefits for their years spent in jobs exempt from Social Security taxes, Social Security instead treated individuals like they had zero earnings. Because Social Security is a progressive program that provides proportionally higher benefits to lower-income earners, all those zeros averaged across 35 years of the earnings calculation made people who worked in both exempt and nonexempt jobs look like they had significantly lower incomes than they did. And it made people who spent their entire careers in jobs exempt from Social Security taxes look like stay-at-home spouses when they in fact worked and earned their own non-Social Security pensions.

When Congress passed the windfall and government pension provisions, it lacked the necessary data to calculate benefits as the program intended, based on individuals’ actual earnings and actual Social Security payroll tax contributions. Consequently, the imperfect provision adjustments mean that some individuals get higher Social Security benefits than they should, and others receive lower benefits than they should.

And a big part of the problem is a lack of understanding and awareness as individuals who worked in jobs exempt from Social Security receive expected Social Security benefit statements based only on their work in jobs covered by Social Security. While these statements include a disclaimer that actual benefits may be lower due to the windfall and government pension provisions, most individuals are nonetheless surprised by those lower benefits.

The data necessary to implement a fair and accurate fix are now available, but the Social Security Fairness Act ignores that data and reverts to the outdated and flawed benefit structure that treats some people with the same lifetime incomes differently and other people with different lifetime incomes the same—the definition of unfair.

There’s a better way to fix the windfall and government pension provisions. By using the data that’s now available, the Social Security Administration can calculate benefits as intended, based on the income that people actually earn and the Social Security taxes they actually pay.

The Equal Treatment of Public Servants Act of 2023 (H.R. 5342) is much closer to a fair and accurate fix for the Windfall Elimination Provision and it would cost one-eighth as much—$24 billion over 10 years and only a “negligible” impact over 75 years. A similar fix for the Government Pension Offset could be incorporated into that act, or introduced as a separate bill to be voted on in the next Congress.