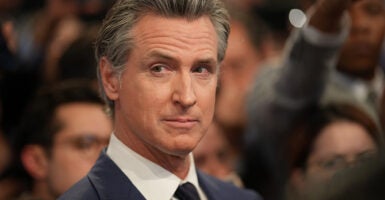

Although Donald Trump’s election was widely seen as a rebuke to the Left’s obsession with race, California Gov. Gavin Newsom has promised to “Trump-proof” his state, and that likely applies to the Democrat’s ongoing plans to give race-based handouts.

This year alone, Newsom signed a slate of reparations bills into law. And although California won’t be handing out checks, its laws are sure to spark more calls from California liberals to take money from Hispanic, Asian, and white Californians and give it to black Californians.

Here’s what California has done so far, including four related laws.

Formal Apology for Slavery

Some 159 years after the 13th Amendment formally abolished slavery, California—which entered the Union as a free state—issued a formal apology to African slaves and their descendants.

The apology, issued Sept. 26, stems from a recommendation by the California Reparations Task Force, a group commissioned to propose a comprehensive state reparations plan. The apology lists the ways in which the state allegedly was complicit in the perpetuation of slavery, from enforcing fugitive slave laws to enacting poll taxes and literacy tests.

No one disagrees that slavery and racial segregation are evil and unjust. In fact, the state of California beat the federal government to outlawing discrimination on the basis of race, sex, religion, and disability status with the Unruh Civil Rights Act of 1959.

But the apology assumes that past discriminatory practices—in place decades, if not centuries ago—have influenced the present outcome of African Americans, committing to “restore and repair” those affected by slavery and racial discrimination with “actions beyond this apology.”

DEI for Doctors

The California State Legislature found that the maternal mortality rate for black women is three to four times higher than white women. In passing a bill known as AB 2319, the Legislature assumed that the cause of the higher maternal and infant mortality rates was discrimination and that antibias trainings were the solution.

The Legislature—distracted by “diversity, equity, and inclusion,” or DEI—doesn’t consider the possibility that higher maternal and infant mortalities could be caused by other factors. Recent scholarship has, however. A study found that higher infant mortality rates for black babies were attributed to the baby’s weight rather than the color of the baby’s doctor.

California disregards this research and instead requires its doctors to spend time checking their biases rather than increasing their education in specialized and high-risk pregnancy cases. The law requires “implicit bias” training and testing for all health care workers in perinatal care.

The training forces professionals to identify unconscious biases and misinformation, “identify barriers to inclusion,” and consult local leaders from “marginalized communities.” The new law is supposed to identify and eradicate all bias, especially for transgender individuals.

Noncompliant organizations will face fines of $15,000 or more and other penalties that the state attorney general deems fit to force health care workers into compliance.

Hairstyle Discrimination

The Legislature also passed a bill, AB 1815, to expand the definition of race in California’s original Unruh Civil Rights Act by including “protective hairstyles” such as braids, dreadlocks, and twists.

But existing federal and state civil rights law already prevents “hairstyle discrimination.” The Unruh Civil Rights Act prohibits discrimination based on race and the “particular characteristics” associated with that race. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 requires those hearing the complaint to determine whether discrimination based on hair reveals an underlying form of racial, sexual, or religious discrimination.

AB 1815 lacks a balance between legitimate reasons to prohibit hairstyles in the workforce and valid claims of racial discrimination. Existing civil rights law recognizes that some hairstyles may be prohibited in certain cases, but also provides exceptions. Instead, AB 1815 relies on racial hairstyle and texture stereotypes and assumes that all hairstyles are acceptable in all cases.

The California legislation also raises several thorny legal questions.

For example, what is the burden of proof to show that a hairstyle is protected? And if a person of one race wears a hairstyle that California stereotypes as being another race’s, is the hairstyle still protective?

Such questions find no answers in AB 1815, which will be a boon to trial lawyers and engender confusion among regulated Californians.

Racial Preferences in Schools

A third bill passed by the Legislature, SB 1348, creates a new designation for California colleges and universities called “California Black-Serving Institutions.”

To earn the designation, at least 10%, or 1,500 students, at an institution must be black. And an institution must try to create equal outcomes among racial groups—what the law calls “equity.”

To keep the designation, institutions must show an increase in the number of black students staying in school and graduating and a decrease in the time it takes black students to graduate. California Black-Serving Institutions must facilitate special outreach and academic services to black students, including affinity centers and “culturally relevant” staff training.

Similarly, a fourth bill signed into law by Newsom in September, AB 1929, requires community colleges and technical education programs to separate student data by race and gender.

The Legislature assumes that discrimination is the cause of all outcome differences in education. California fails to account for other factors—including cultural differences, morals, and an individual’s motivation—that shape outcomes.

In doing so, state lawmakers perpetuate the same arbitrary racial preferences already deemed unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court.

It seems that California is concerned with the outcome of only one racial group, because it is oddly silent about the graduation rates of Latinos and other minorities.

Although reparations proposals are a high priority for Newsom and California’s Legislature, they are growing increasingly unpopular with Californians. One study reveals that less than half of Californians have a favorable view of the reparations task force; another survey shows that 59% of Californians say they oppose cash payments as a form of reparations.

Nevertheless, “this is just the beginning,” says California state Sen. Steven Bradford, a Democrat.

With California preparing to mount a full-blown resistance to Trump’s anti-woke agenda, Californians likely can expect a lot more race-obsessed policy out of Sacramento.