The Rust Belt community of Springfield, Ohio, now has a page on its website dedicated to answering common questions about the flood of illegal aliens, mostly Haitians, who have arrived there in recent years.

“The City of Springfield has experienced a surge in our population over the last several years, primarily due to an influx of legal immigrants choosing Springfield, Ohio as their new home,” the city’s website states, officially describing illegal aliens as “legal immigrants.”

Clark County, situated between Columbus and Dayton, includes Springfield. The county’s migrant population is estimated at 12,000 to 15,000, according to Springfield’s “Immigration FAQs” webpage.

Others, including one state representative for Springfield, estimate the total migrant population to be closer to 20,000. (According to the 2020 census, the city’s total population was 58,000.)

Despite the city’s declaration that the Haitian migrants are “legal,” the reality is nuanced at best.

“The Haitians in Springfield, Ohio, are in various immigration statuses,” according to Simon Hankinson, senior research fellow in the Border Security and Immigration Center at The Heritage Foundation.

Although a “small number” of the Haitian migrants may fall under legal resident status, Hankinson said in an email to The Daily Signal, the majority fall into one of three categories:

- Recipients of Temporary Protected Status, which the president can assign to nationals of designated countries for (supposedly) temporary periods if wars, natural disasters, or other one-off events render their country incapable for a time of reabsorbing them.

- Those who arrived illegally between ports of entry … but [are] soon released with a Notice to Appear in immigration court in a lengthy process to deport (“remove”) them.

- Those paroled in via the Biden administration’s highly disputed, and arguably unconstitutional, [parole for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans] or CBPOne programs.

Referring to anyone in these three categories as “‘legal immigrants’ is wrong,” Hankinson told The Daily Signal, despite what Springfield officials say on the city website.

Temporary Protected Status

“Haitian immigrants are here legally, under the Immigration Parole Program,” Springfield officials state on the website. After their arrival, the page adds, “migrants are then eligible to apply for Temporary Protected Status.”

Temporary Protected Status is granted to residents of a specific nation or region who are in America “due to conditions in the country that temporarily prevent the country’s nationals from returning safely, or in certain circumstances, where the country is unable to handle the return of its nationals adequately,” according to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

Haitian nationals in the U.S. under Temporary Protected Status are permitted to stay in the country through Feb. 3, 2026.

“Temporary Protected Status is just … when the federal government simply pauses enforcement of immigration law – i.e. deportation – for certain nationalities,” emailed Hankinson, who spent more than 20 years working as a foreign service officer.

The designation “confers no permanent legal status,” he said. “Those with parole, by definition, have not been legally admitted.”

Parole Program

In January 2023, the Biden-Harris administration announced what it called new “legal pathways” for Venezuelans, Nicaraguans, Haitians, and Cubans to come to the U.S.

“Up to 30,000 individuals per month from these four countries, who have an eligible sponsor and pass vetting and background checks, can come to the United States for a period of two years and receive work authorization,” the White House announced in a fact sheet.

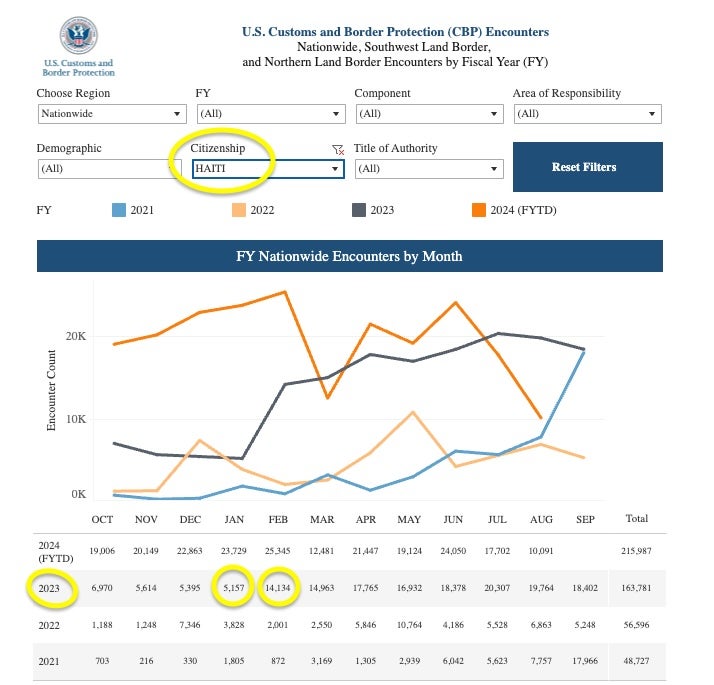

Following the announcement, U.S. Customs and Border Protection reported a sharp increase in the number of Haitians arriving at the border and at official ports of entry.

In January 2023, the month the White House announced the administration’s new immigration program, 5,157 Haitians arrived at or between a port of entry. But that number jumped to 14,134 the following month and, with some fluctuation, continued to climb over the next 18 months.

In total, more than 350,000 illegal aliens from Haiti have arrived on American soil since the Biden-Harris administration launched the program. Also accepted were up to 360,000 Venezuelans, Nicaraguans, Haitians, and Cubans a year.

The administration temporarily paused the program over the summer, however, due to fraud concerns.

The Department of Homeland Security, the parent agency ultimately responsible for border security, discovered the use of fake Social Security numbers, phone numbers, and addresses on application forms. DHS also discovered that, among over 100,000 application forms, the same sponsors appeared 3,218 times—meaning one sponsor was filling out 20 or more forms.

After a monthlong pause, the Biden-Harris administration announced at the end of August that the program was resuming with “new procedures” to strengthen its integrity.

Calling Them ‘Refugees’

Springfield also refers to the Haitian migrants as “refugees.”

“Refugees are admitted to the United States based upon an inability to return to their home countries because of a ‘well-founded fear of persecution’ due to their race, membership in a particular social group, political opinion, religion, or national origin,” according to the American Immigration Council.

Every year, the president and Congress agree on a ceiling for the number of refugees who will be accepted into the U.S. For fiscal year 2024, which began Oct. 1, 2023, the Biden-Harris administration capped the number of admissible refugees at 125,000.

Since then, more than 215,000 Haitians alone have arrived at or between a U.S. port of entry.

Refugees apply to come to America while still outside the country, but asylum-seekers are those who arrive and request entry. Similar to a refugee application, U.S. law requires an individual seeking asylum to show a “well-founded fear of persecution” because of his or her race, religion, nationality, political affiliation, or membership in a specific social group.

“Those released with a Notice to Appear to later (in theory) claim asylum are also illegal until and unless they succeed in gaining that protection via immigration judges, Hankinson said in his email to The Daily Signal. “They are not ‘refugees’ either, because they do not have that status and Congress explicitly didn’t want presidents to use mass parole as a way around the U.S. refugee admissions process.”

Why Haiti?

Haiti is among the 25 poorest nations in the world, according to Global Finance magazine. The Caribbean country has been beset by gang violence for years.

Haitian President Jovenel Moïse was assassinated in 2021, leading to an increase in unrest in the already tumultuous nation.

Given the unrest in Haiti, it is not surprising that individuals would seek a better life in the U.S., especially given the opportunity offered by the Biden-Harris administration, Hankinson noted.

“The Haitians in Springfield are hapless, perfect examples of the dysfunction in our immigration policy and how one administration’s refusal to do its duty and enforce our laws creates a giant magnet for migration that American states, cities, and towns have no means to absorb,” the Heritage research fellow said.

Effect on Springfield

Most Americans were unaware of the thousands of Haitian migrants who had arrived in Springfield, Ohio, until the presidential debate Sept. 10, when former President Donald Trump said illegal aliens were “eating the pets” in Springfield.

No convincing evidence indicates illegal aliens are eating dogs, cats, and other pets in Springfield, but at least one resident reported seeing a small group of Haitians carrying geese away.

It is the “lower cost of living and available work,” not geese, that accounts for the influx of predominantly Haitian migrants, according to city officials.

Zillow reports that the average cost of renting a house in Springfield is $1,645 a month, a $445 increase since last year but significantly lower than the national median of $2,300 a month.

One Haitian migrant, Patrick Joseph, told the Dayton Daily News that when he arrived in Springfield in August 2021, he was living in a three-bedroom house with “more than 20 people.”

A landlord can “just rent the bed in the bedroom,” Joseph said. “A room can sleep like 10 people. And sometimes the house has only one bathroom.”

While Haitians are moving in, U.S. citizens such as Dustin Berry are choosing to leave Springfield.

The move out of Springfield was one he had planned to take, Berry told The Daily Signal, but the influx of Haitian migrants moved up his timeline because he was afraid that housing values would decrease.

“Over the last year or two, we noticed that the … quality of the neighborhood we were in at the time was kind of going downhill, getting a little bit more overpopulated,” Berry said.

Berry also expressed concern over car accidents related to Haitian migrants’ lack of understanding of U.S. traffic laws, “and understanding just the basic operation of a motor vehicle.”

On the city website, Springfield officials acknowledge: “Anecdotal data shows that Haitian drivers are having a high rate of accidents, and one resulted in a bus crash that took the life of an 11-year-old last year.” (The child, Aiden Clark, was killed when a vehicle driven by a Haitian migrant hit his school bus.)

The “language barrier” also is a central concern, said state Rep. Bernie Willis, a Republican who represents Springfield.

“This is creating challenges for educators, law enforcement, health care professionals, and other service providers,” Willis said in a written statement. “Translators are needed at public service departments, and these additional costs are straining already stretched resources.”