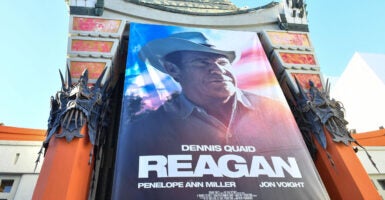

The verdict is beginning to settle in on the new Ronald Reagan biopic, and, like RR himself, the jury is split.

For the pundits and the critics who find everything about the 40th president cloying and simplistic, the movie is irritatingly pat. Look as closely as one can, they say, there isn’t a single nuance or complication at hand on which to dwell. For the audience attending “Reagan,” these qualities of sweet simplicity are among the film’s virtues. The movie is a smash, currently the third-highest grossing film in America.

Anyone looking for an objective take on this version of Reagan’s life will have to continue looking elsewhere. I rest easily among those who, like Paul Kengor who wrote the book on which “Reagan” is based, regard the 1980s as an era of American renewal that came about not only because of Reagan’s creedal optimism but because of his profound convictions about America as a moral project.

I was a relatively new arrival in Washington when I joined the Reagan administration as a writer in the correspondence shop in 1981. I had been drawn to the city not out of a desire for political engagement per se but as a reaction to a set of issues that required a national reset. Primary among these was the Roe v. Wade decision of 1973, which had declared open season on children before birth. I had ethical views on the issue but more simply than that, the ruling struck me as grossly unfair, a purchase of power over the most vulnerable at the service of a ruthless elite devoted to population control and quality control of their “inferiors.”

These topics, which Kengor has explored elsewhere in his voluminous historiography on Reagan, are not the subject matter of the new film. The many other areas where Reagan had impact—deregulation, tax cuts, judicial appointments, patriotism, social policy—are only glancingly touched upon in the two-plus hours of “Reagan.” This biopic is a Cold War story, as evinced by the narrative device of having an older-and-wiser former KGB man named Viktor Petrovich relate the history of the conflict with the Soviet Union that motivated Reagan’s rise.

That said, the film offers insights into that motivation, which deployed both Reagan’s native optimism and his deep Christianity, a fact I am persuaded helps feed the political and media critics’ inability to perceive him accurately. His biography combines these factors as well.

Reagan emerged on the political scene through his communication gifts, both as an actor and beyond that as a gifted writer who wrote his own scripts for decades. He was known as a man of the West, who loved the novels of Louis L’Amour, to whom he awarded a Congressional Gold Medal at a White House event in 1982.

But Reagan’s ride on the open range of American promise was rooted in the small-town values of his youth in the American Midwest. He struggled with the alcoholism of his father Jack but drew from his parents, especially his mother Nelle, a hatred of racial prejudice and a deep faith in biblical Christianity. His opposition to communism, which above all substitutes an omnipotent state for the sovereignty of God and opens the door to atrocity, set the stage for his actions as the president of the Screen Actors Guild and then of the United States.

This was by no means simple, of course. The film captures effectively how Reagan’s faith carried him through actual and potential calamity, from the March 1981 assassination attempt at the Washington Hilton to a tense confrontation with a mystified Mikhail Gorbachev, who makes an arms reduction offer he believes Reagan can’t refuse. “Nyet,” Reagan says. The goal for Reagan was not the political bonus at home Gorbachev dangled before him but an end to the regime of Mutual Assured Destruction—MAD—that had brought the United States and the Soviet Union to the brink of annihilation over Cuba and, as the film shows, a Soviet misinterpretation of an atmospheric event in 1983.

Portraying Reagan is in many ways an impossible task. The film is at its best in its depictions of his Christian character and unwillingness to accept the status quo. In one of his encounters with Secretary Gorbachev, the Soviet premier describes the Orthodox Christianity of his own grandmother and Reagan responds with a description of Nelle’s faith, saying he was sure the two women would have gotten along very well. An actual clip of Gorbachev in 2004 at the U.S. Capitol, laying his hand on the American flag as it drapes Reagan’s casket, is one of the film’s many moving moments.

“Reagan” could have done more to elucidate the depth of Ronald Reagan, a point on which both liberal and conservative critics of the movie agree. The challenge, despite the film’s length, is the timespan it covers and the pace required to visit his childhood, lifeguarding and college years, stint in Hollywood, governorship, loss to Gerald Ford in 1976, two terms as president, and beyond.

The worst of his political critics often dismissed him as uninformed, and the film could have done more to dismiss such nonsense. Reagan read widely and filled yellow legal pads with writing throughout his public life and his presidency, as his archives and books like “Reagan: In His Own Hand” scrupulously document.

Seeing his correspondence every day as I did in his second term, I easily attest to his familiarity with issues across the domestic and international spectrum. His was a great presidency peopled with men and women who shared his vision for a nation of moral purpose committed to self-governance at home and peace, through strength, abroad.

But he was also a man gifted with connection as well as communication skills, a trait the film captures in one of its best vignettes, where he delays an official event to write a letter to a young boy over the demise of a goldfish the boy had entrusted to Reagan’s care. The Reagan I worked for had thousands of such moments with people in his orbit.

The full title of Kengor’s book is “The Crusader: Ronald Reagan and the Fall of Communism.” Reagan’s warning about “freedom never being more than one generation away from extinction” still applies. A revanchist Russia under the Putin regime has East and West at each other’s throats with drones raining death and mutual destruction from Kyiv to Moscow. There are no urgent questions of the past that are not questions today.

What would Ronald Reagan do now? He would certainly see that communism has not fallen. But he would likewise see the evils of war, and the dread nightmare of nuclear conflagration, and he would be praying, leading, and working for peace—as he said in his First Inaugural, “Peace is the highest aspiration of the American people. We will negotiate for it, sacrifice for it; we will not surrender for it, now or ever.”

The best Ronald Reagan biopic has not yet been made, but this latest effort is still timely and powerful. It echoes his vision, inscribed on the Reagans’ memorial looking westward to the sea in Simi Valley: “I know in my heart that man is good, that what is right will always eventually triumph and there is purpose and worth to each and every life.”

Chuck Donovan joined the White House staff in April 1981 and served as deputy director of presidential correspondence from 1986-88.

Originally published by The Washington Stand

We publish a variety of perspectives. Nothing written here is to be construed as representing the views of The Daily Signal.