Critical race theory gripped the nation’s attention after the summer of 2020 and the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. According to Google Trends, the search term peaked in June 2021, then interest tapered off going into 2022.

But the radical philosophy has not disappeared from public life.

Rather, Americans are more familiar with this worldview that claims racism is the cause of every negative event in politics, education, economics, and culture.

More Americans can recognize that ideas such as diversity, equity, and inclusion; microaggressions; and white privilege are creatures of critical race theory and trace back to the Marxist claim that the world is defined by racial power struggles.

K-12 education remains a crucial part of the national conversation on how the theory is teaching young people to consider themselves victims instead of individuals responsible for their own choices and decisions.

For example, policymakers in California and Minnesota have made “intersectionality”—critical race theory’s idea that we are oppressed in intersecting ways, based on our race, sex, and other immutable characteristics—a central component of their states’ ethnic studies curriculum.

This feels strategic: The now-deceased critical race theory scholar Derrick Bell wrote that he hoped the theory would inspire academic “resistance” to America’s ideals of freedom and equality under the law, which would lead to wide-scale “resistance.”

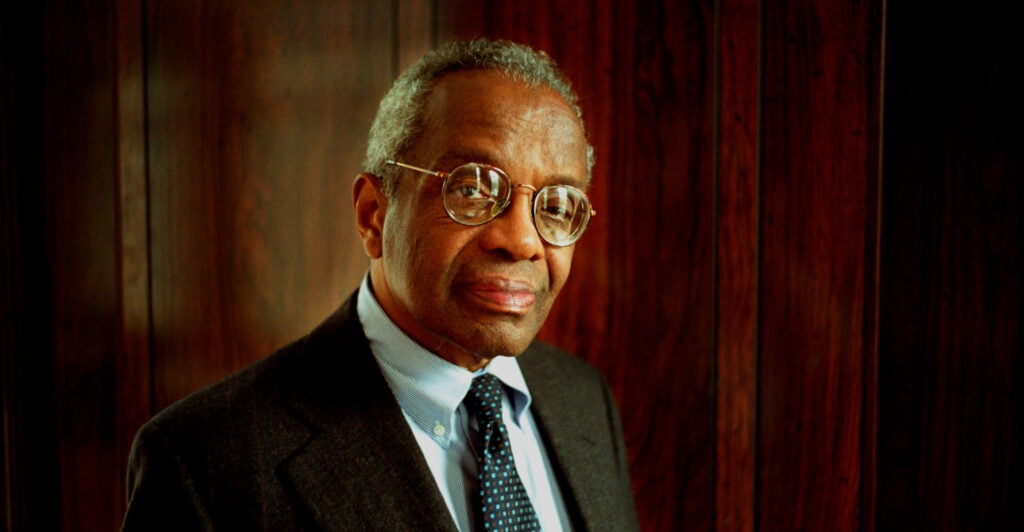

The now-deceased Derrick Bell, the first tenured black law professor at Harvard University, is widely regarded as being the originator of critical race theory. (Neville Elder/Corbis/Getty Images)

Not all state lawmakers are allowing this radical movement to march through their educational institutions, however. In a review of the laws adopted in 14 states since 2020, we found staunch rejection of the use of critical race theory in K-12 schools.

The work is not finished, even in many of those states, however. Earlier this year, a federal judge overturned a law adopted by New Hampshire officials that was meant to prevent the theory from spreading racial discrimination in the state’s elementary and secondary schools. The judge said that key provisions in the law were not well-defined, sending lawmakers back to the drawing board.

State lawmakers should continue to pursue proposals that reject critical race theory, but they must be specific about what they are prohibiting.

>>>Our latest report, “Rejecting Critical Race Theory in State K–12 Laws,” offers several ideas.

State policymakers should prohibit the application of the theory in the form of compelled speech and mandatory racial affinity groups and other clear examples of racial discrimination.

Actions such as those and more have been widely documented in schools from Pickens, South Carolina, and Wellesley, Massachusetts, to Los Angeles and Seattle.

Some state legislation offers solid models to follow. Montana Attorney General Austin Knudsen issued a binding opinion that prohibited compelled speech and said, “Compelling students, trainees, or anyone else to mouth support for those same positions not only assaults individual dignity, it undermines the search for truth, our institutions, and our democratic system.”

Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin issued an executive order that said “‘inherently divisive concepts’ means advancing any ideas in violation of Title IV and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964” and prohibited academic instruction that furthered such concepts.

Lawmakers should prohibit school officials from forcing students and teachers to defend, affirm, or profess ideas that come from critical race theory as a condition of enrollment, course completion, hiring, retention, or promotion.

State policymakers should also ban the sort of discriminatory conduct that critical race theorists deem appropriate—but that are, in fact, racist—to fulfill their discriminatory aims. For example, critical race theorists have advocated for racial preferences in college admissions, which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional in 2023.

A law is on much stronger legal ground when it protects someone from being forced to say something than it is when it prohibits them from saying something. Instead of “banning” critical race theory from classrooms, state education officials should update K–12 academic standards to discuss the institution of slavery in 19th-century America, the failure of Reconstruction efforts after the Civil War, and the Jim Crow era. At the same time, educators should explain the significance of the end of systemic racism, both legally and culturally, through federal civil rights laws.

Critical race theory’s racist ideas—DEI, intersectionality, and more—are lessons from the “school of resentment” as literary critic Harold Bloom said. Children need to be taught to aspire to something, not resent everything.

Lawmakers’ rejection of critical race theory in schools is essential.