As Americans focus on the presidential election campaign and domestic political uncertainty, China’s large-scale military exercises loom on the horizon after an unusually provocative summer of such activity.

Tensions across the Taiwan Strait simmer and a standoff with the Philippines persists in the South China Sea, and China is becoming more direct with America and its allies, indicating its approach is evolving quickly.

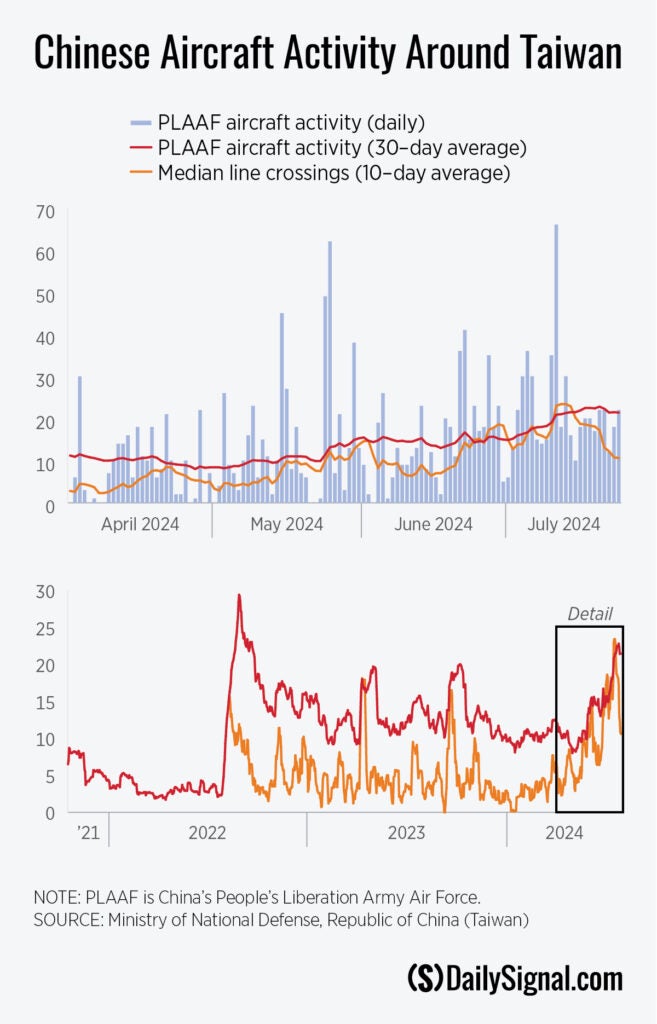

First, activity over the Taiwan Strait by China’s air force (the People’s Liberation Army Air Force) has remained at elevated levels since 2021, but recently set new records.

On July 11, for example, 66 Chinese aircraft were detected over the Taiwan Strait, the highest single-day activity this year. Even more concerning, 56 of the aircraft crossed over Taiwan’s side of the strait, constituting the highest single-day crossing of the median line since recordkeeping began in 2020.

China’s increased military activity also led to the highest recorded 10-day average median line crossing: 23.4 aircraft. Such crossings are highly provocative. That said, activity over the past few months continues an upward trend.

The recent wave of intimidation by the Chinese air force, known as PLAAF, began soon after a July 10 meeting between the top U.S. envoy to Taiwan, Raymond Greene, and Taiwan President Lai Ching-te. Greene pledged increased measures to defend Taiwan, and his visit remains the most plausible reason for China’s response, given historical precedent.

But it’s worth noting that the Chinese escalation also coincided with NATO’s 75th-anniversary summit in Washington, which ran from July 9 through 11, where China was mentioned on multiple occasions.

With surprisingly stern language, the NATO summit’s communique warns that “the stated ambitions and coercive policies [of the Chinese Communist Party] continue to challenge [NATO’s] interests, security and values.” The alliance’s communique reiterates that China “cannot enable the largest war in Europe in recent history without this negatively impacting its interests and reputation.”

In all, China is mentioned 14 times in the document, demonstrating NATO’s first clear acknowledgment that transatlantic security is now deeply intertwined with issues emanating from the Indo-Pacific.

Participation by South Korea, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand in the NATO summit further signals the alliance’s deepening concern for the region and how a war there would affect European security.

In response to NATO’s statements, China’s Ministry of Defense offered stern words of its own on the same day as the communist regime’s record aircraft activity over Taiwan. China insisted NATO’s statements constitute “belligerent rhetoric,” making clear that China “will firmly uphold its own sovereignty, security and development interest.”

China’s dissatisfaction with the U.S.-led world order and its reach in the Indo-Pacific is well known, and that animosity is being played out increasingly in military shows of force.

Chinese and Russian forces also gathered June 25 near the Blagoveshchensk–Heihe Bridge, which connects Russia and northeast China.

According to China Military, a publication funded by the People’s Liberation Army, priorities included “encirclement and capture operations” within the domains of “aerial reconnaissance, surface interception, and ambushes on the shore.”

China said the motivation for the military exercise was to combat separatism—a justification especially significant considering that China quickly labeled Lai, Taiwan’s president, a “separatist” after his May 20 inauguration.

China’s summer activity is expanding to include a variety of other military exercises. On July 13, China carried out multiple waves of missile tests in Inner Mongolia. China’s Rocket Force, responsible for the tests, likely will play a critical role in the regime’s military operations in a war over Taiwan’s future.

As such, these tests also serve as preparation for a potential Taiwan war scenario and for more provocative exercises with the Chinese navy and air force during exercises expected soon in the South China Sea.

If these missile tests are deemed successful by Chinese leader Xi Jinping, he may decide to execute a more complex and provocative challenge in the region.

NATO’s concern is reinforced by China’s increasingly apparent support of Russia in the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war. More directly, China and Belarus began joint exercises July 8 dubbed Eagle Assault 2024.

This coincided with a visit to Warsaw by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, during which Ukraine and Poland signed a security agreement. The China-Belarus military exercise took place just 17 miles from the Ukraine border and 2 miles from Poland.

Like Russia, Belarus is a member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a Eurasian economic and security coalition. This partnership provides China with an impetus for a greater military presence in Europe, but how it serves China’s strategic interests is less clear.

However, this military exercise, planned well in advance and coinciding with the NATO summit in Washington, certainly underscores China’s dismay with Europe’s demurring on Chinese trade and increasing realization of it as a threat.

Earlier this month, China also deepened military cooperation with the United Arab Emirates and Laos, respectively, through two exercises: Falcon Shield 2024 and Friendship Shield 2024.

While noteworthy, neither exercise raised a red flag militarily. But the exercises did demonstrate China’s continued willingness to engage favorably with partners who are amenable to accepting its position on Taiwan.

In the South China Sea, a familiar hotspot, China and Russia are increasing joint military engagement, as they are elsewhere. On July 14, Joint Sea 2024 began at a naval port in Zhanjiang, southern China, headquarters for China’s South Sea fleet. Both countries conducted a variety of anti-submarine and air defense exercises.

At the same time, a separate Chinese-Russian naval patrol entered the South China Sea, passing close to Japanese islands, in what the two nations described as a routine operations unrelated to the geopolitical climate. The joint forces simulated missile firing and cross-deck landing operations and carried out gun drills.

Military exercises are routinely scheduled during the summer months. But the recent activity amid regional and global tensions demonstrates an unusual increase in Beijing’s risk-taking not seen in previous years.

China also is finding ways to test the United States more directly.

Case in point: Chinese and Russian bomber aircraft were detected July 25 and intercepted by NORAD as they flew into the Alaska Air Defense Identification Zone off the coast of Alaska.

This is the latest example of China and Russia’s deepening defense ties and marks the first time two U.S. adversaries deployed strategic bombers together near the United States. The Chinese aircraft in question was the H-6 bomber, capable of carrying nuclear weapons and sometimes active over the Taiwan Strait.

This latest Alaska incident came just weeks after Chinese warships were detected July 6 and 7 near Alaska’s Aleutian Islands. While steering clear of territorial waters, the Chinese vessels passed into the exclusive U.S. economic zone. This marks the fourth consecutive year that China’s naval assets have been detected near Alaska—another component of China’s upward-trending assertiveness in the Pacific.

Only days after that, the Chinese aircraft carrier Shandong, along with two missile destroyers and a frigate, made headlines as they passed close to the Philippines on the way to the Western Pacific to carry out another set of drills.

In a departure from the norm, the carrier group didn’t pass through the Bashi Channel separating Taiwan and the Philippines, but instead went through the Balintang Channel, which runs between two groupings of some of the Philippines’ northernmost islands. This diversion, while subtle, signals continued aggression toward the Philippines, where U.S. Marines recently held joint exercises.

Vietnam also has seen tension before with China in the South China Sea, but unlike the Philippines, Hanoi’s most recent Chinese-style artificial island expansion hasn’t drawn noticeable displeasure from Beijing.

Since its positive diplomatic developments with both the U.S. and China last September and December, Vietnam has rapidly pursued island reclamation in the South China Sea. Discovery Great Reef, South Reef, Namyit Island, and Pearson Reef all received dozens of acres of land expansion since November, according to the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative.

Barque Canada Reef continues to be Vietnam’s largest outpost and recipient of recent efforts, gaining 174 acres of land over the past six months. In all, 692 acres have been added since November. This is up from 404 acres the prior year and represents a 100% increase in land reclamation since 2022.

Manila’s seemingly minor actions prompted violent responses from Beijing and Western states’ diplomatic activities triggered military posturing, but China hasn’t condemned Vietnam’s sweeping reclamation campaign.

Why is China choosing not to back down over the Philippines while simultaneously turning a blind eye to Vietnam’s recent surge of island-building in the same region?

China’s selective enforcement of its own standards points to the likelihood that its reactions are reserved for the U.S. or actions that Beijing perceives to be prompted by or indirectly benefit the U.S.

As tensions over Taiwan and features in the South China Sea reach a boiling point, efforts to understand Beijing’s thinking are paramount and could offer ways to better address and mitigate its escalations.

America’s lack of strategic direction is commensurate with China’s recent threatening actions. Beijing’s timing, location, and choice of willing partners lessen the probability that its activities happen at the same time by coincidence and hold no greater meaning.

Washington must be alert in the coming months, particularly around Thursday, Aug. 1, the anniversary of the founding of the People’s Liberation Army—a symbolic date that China often uses for strategic messaging.

The United States has been in China’s crosshairs for years. But given its recent conduct, Beijing is more likely than ever to double down on its posturing and take on added risks with Washington and allies such as the Philippines.