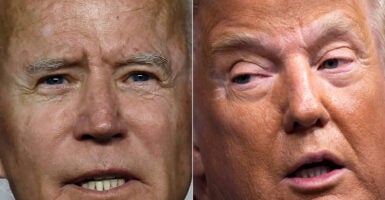

As the first presidential debate between former President Donald Trump and President Joe Biden approaches, it’s a good occasion to settle another debate; namely, the long-running dispute over how to define conservatism.

Since before Trump was elected, think tankers and pundits on the right have spent large sums of time and money sorting themselves into separate tribes and attacking their rivals. “Compassionate-conservatives,” “freedom-conservatives,” “national-conservatives”—the list of these hyphenated conservatisms goes on.

But when I talk to grassroots Americans, many of whom plan to vote for Trump this November, they never talk about what type of conservative they are. They’re too busy telling me the urgency of saving the country.

In fact, most of these Americans know that internal squabbling jeopardizes the conservative movement, making it easy for the establishment and the Left to prevail. That’s not to say we all have to agree on policy—quite the opposite.

The debates we’re having on the Right over family policy, trade, technology, and other areas are long overdue. But instead of dividing us into factions, these debates should remind us of our common goals and lead us to be united against an increasingly radical Left.

Russell Kirk wrote that “the conservative person is simply one who finds the permanent things more pleasing than Chaos and Old Night.” Those permanent things include the American family, our founding, faith, our ways of life, and our shared traditions—things every conservative can agree on.

Policy choices, while important, are necessarily temporary and must adapt to changing circumstances.

For too long, the Right has been the side of “no,” defining itself by what it’s against, not what it’s for. The result is a movement so accustomed to opposition that it turns inward against itself and splinters. By defining ourselves in terms of what we love—the permanent things—we can unite our house and stand firm against the forces threatening our shared inheritance.

The Heritage Foundation has worked hard to put this into practice. Last year, we convened hundreds of authors to write our Mandate for Leadership, a nearly 900-page list of policy proposals for the next president. We found a surprising amount of agreement from this diverse group, including on civil service reform, regulatory improvements, trade policy, and more. We welcomed the internecine debate as well: On trade and labor, we couldn’t find total agreement, so we presented two alternative views.

While it’s easier to have rival conferences and trade white papers back and forth, the hard work of convening, debating, and working to save what we love is vital to our movement’s success.

It’s no coincidence that in the post-Reagan years, the number of conservative “tribes” exploded while electoral victories dwindled. Voters want to see fresh ideas and a positive, unifying vision. Peddling old ideas while insulting your allies is an easy way to lose your audience.

America is divided enough already. It is time for all conservatives to drop the hyphen, unite, and put the permanent things first.