Marriage is increasingly rare among younger American adults. Back in 1970, 83% of Americans aged 25 to 34 were married. Today, only 41% in that age range are married.

And as marriage has fallen out of favor, fewer and fewer children are growing up in married, two-parent homes—and fewer babies are being born at all.

In 1970, the birthrate was 50% higher than it is today, and only 10% of U.S. children were born to unwed mothers.

More recently, a 2019 Pew Research study found that the U.S. had the highest rate of children living in single-parent households out of 130 countries analyzed.

There are many factors that have contributed to the decline in marriage, but federal and state tax systems that often penalize marriage—especially for lower-income Americans with children—exacerbate matters.

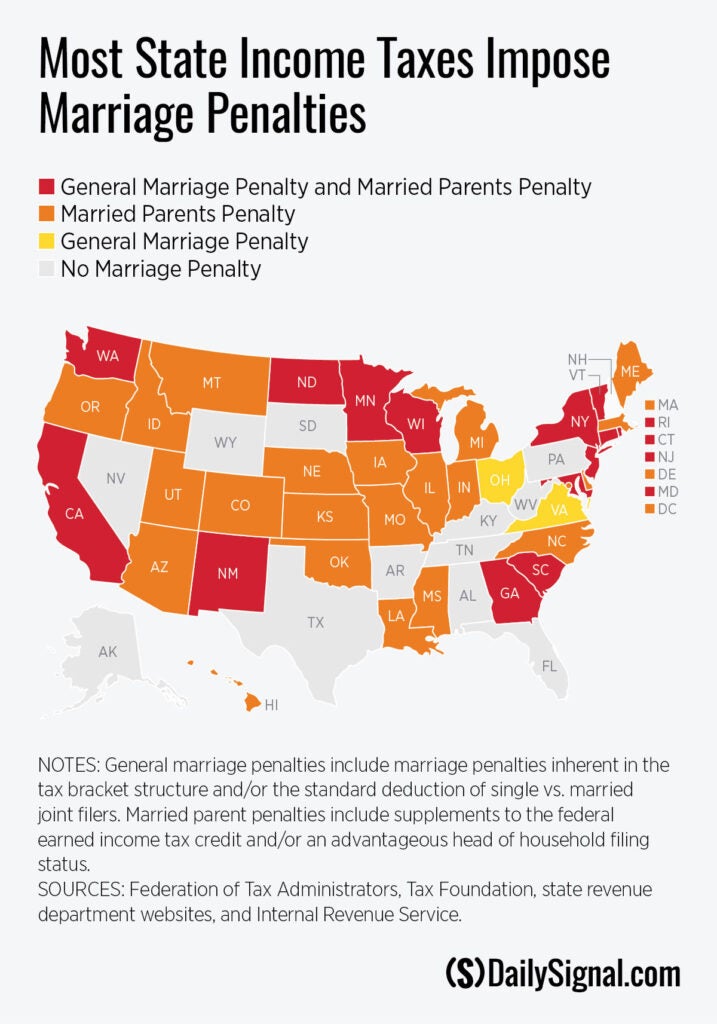

The federal income tax, plus the state income taxes of at least 37 states and the District of Columbia, impose marriage penalties in some situations.

There are three main ways that marriage penalties appear in the tax code.

First, with a progressive income tax, the combined dual incomes of married joint filers can push couples into higher tax brackets than if they were both single, unless the standard deduction and bracket thresholds for married filers are double that of single filers.

Second, the federal tax code and some states provide generous tax credits contingent on taxpayers having low-enough incomes. In many cases, a spouse’s income can disqualify a household for credits such as the federal earned-income tax credit (also known as the EITC), which can pay or reduce the taxes of low-income parents by as much as $7,430.

Third, the federal tax code and many states provide more generous tax brackets for individuals filing as “heads of household”—especially when used in conjunction with the EITC. (Head of household is the filing status used by most single parents.)

The federal tax system hasn’t always penalized marriage.

In 1950, the tax code was at least as favorable for married couples compared with unmarried tax filers in almost all situations.

Then, Congress created the head-of-household filing status in 1951; introduced marriage penalties into the standard deduction and the income-tax brackets in 1971 and 1977, respectively; enacted the EITC in 1975; and greatly expanded the EITC between the mid-1980s and mid-1990s.

Since most states’ income-tax codes largely conform to the federal tax code, many of them automatically compounded the new federal marriage penalties.

As all this was happening in the federal and state tax systems, President Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” programs were simultaneously wreaking havoc on marriage from outside the tax code starting in the mid-1960s.

The massive expansion of federal welfare programs skewed heavily toward single mothers, which exacerbated intergenerational poverty by pushing lower-income Americans away from marriage and depriving whole communities of children of the profound benefits of growing up in intact two-parent families.

People often overlook marriage penalties that apply specifically to parents.

Lawmakers in some states have purged marriage penalties from their tax brackets, but retained the marriage penalties related to the head-of-household filing status and the EITC. In other words, they’ve eliminated marriage disincentives for those who don’t have or plan to have children, but they continue to discourage the marriages of parents and of prospective parents.

States that leave in place marriage penalties for parents are missing the most important target. The public interest in the institution of marriage is first and foremost because married, two-parent homes provide the best environment for raising children. Children from two-parent homes fare far better on a host of measures, including educational attainment, emotional health, and the likelihood of delinquency or incarceration.

States can avoid marriage penalties by eliminating the income tax.

Eight of the 13 states that avoid marriage penalties are zero-income tax states. Short of that, most other states that avoid marriage penalties are either flat-tax states or they do so by giving married filers the option to file separate returns as though they were single.

Of course, residents of all 50 states face potential marriage penalties on their federal taxes. In some cases, that penalty can be as high as 12% of a couple’s total combined income. Marriage penalties in the welfare system can also add up to tens of thousands of dollars.

Surveying the damage that public policy has done to marriages and families, two things are clear:

- Incentives matter.

- The law of unintended consequences almost always applies to government programs.

Conservative lawmakers should be mindful of these realities as they seek to pick up the pieces and set policies that allow for the restoration of the American family.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email [email protected] and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the URL or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.