A leading Asian studies expert is weighing in on how the U.S. can diminish the threat China poses to Taiwan, even as tensions between the two countries remain high.

“I think the first thing we need to do is clear a backlog of arms sales to Taiwan. We sell Taiwan advanced military hardware, and a number of important platforms that the Taiwanese have purchased have been backlogged, and this has been going on for years now,” says Jeff Smith, director of The Heritage Foundation’s Asian Studies Center. (The Daily Signal is the news outlet of The Heritage Foundation.)

“The second thing we need to do, I think, is help the Taiwanese to develop even better deterrence strategies and denial strategies and acquisitions,” Smith says. “What can we do? What are the most effective military platforms that Taiwan could purchase and use in order to deny China if it decides to launch an invasion or at least to hold out long enough for the cavalry?” It’s widely though that the U.S.—and possibly others, including Australia and Japan—would intervene in the event of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan.

Smith joins today’s episode of “The Daily Signal Podcast” to discuss how the Chinese government has infiltrated our lives; The Heritage Foundation’s newly released report “Winning the New Cold War: A Plan for Countering China”; and the U.S. fentanyl crisis.

Listen to the podcast below or read the lightly edited transcript:

Samantha Aschieris: Jeff Smith is joining today’s podcast. Jeff is the director of the Asian Studies Center here at The Heritage Foundation and the author of “Asia’s Quest for Balance: China’s Rise and Balancing in the Indo-Pacific” and “Cold Peace: China-India Rivalry in the Twenty-First Century.” Jeff, thank you so much for joining us.

Jeff Smith: Great to be here.

Aschieris: So, The Heritage Foundation released a new paper titled “Winning the New Cold War: A Plan for Countering China.” The paper says China is the most capable geopolitical adversary the U.S. has faced since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Why is that?

Smith: Well, I would might even amend that statement and say that in some ways it’s a more capable geopolitical adversary than the Soviet Union.

And the big reason for that is that while the Soviet Union was certainly a military powerhouse with a huge arsenal of nuclear weapons, it was an economic middleweight. It was really never an economic peer of the United States and it was largely isolated from the West in terms of trade and investment. And so it punched above its weight in the military realm, but not in economics.

China, unfortunately, is an economic superpower, and now the second-largest economy in the world by nominal [gross domestic product], by some accounts the size of its economy has already overtaken the United States in terms of purchasing power parity, and it is deeply enmeshed in the global trading system. It’s the No. 1 trading partner of the U.S., many years. It’s the No. 1 trading partner of many of our allies and partners around the world.

And it’s used that economic heft to expand its military capabilities considerably. And if you project out into the future, it’s quite likely that China could reach parity with the United States in terms of military spending at some point this century.

It also has the relative advantage of playing in its backyard. So in most scenarios where we envision potential friction or conflict between the United States and China, they’re in the Indo-Pacific, or in the Western Pacific. And so in those scenarios, China is able to bring almost all of its military resources to bear close to its homeland, whereas the United States, we’re spread fairly wide. We have responsibilities in the Atlantic and Europe, South America.

And so that’s concerning to planners and strategists here in the U.S. That does make it a very capable adversary with the economic foundation and wherewithal to really challenge the United States this century, and that’s concerning.

Aschieris: Something else that I find concerning is the influence of China right here in the United States from universities to buying U.S. farmland. China seems to be involved with many aspects of our lives, whether we know it or not. Can you speak more about how the Chinese government has infiltrated our lives?

Smith: Yeah, you’re absolutely right, and that’s another thing that makes China unique from the Soviet Union, and in some ways more dangerous. Certainly makes the United States more vulnerable to China than we were to the Soviet Union.

So, we treated the Soviets as an adversary basically from the get-go, from the moment World War II ended. We tactically partnered with the Soviets during World War II and almost immediately after the war, we recognized that this was a major rivalry, and so we essentially shut them out, which made a lot of sense to do to an adversary.

Our history with China is much different in that we pursued this engagement strategy with them since the 1970s that said, by doing more political and economic engagement, eventually we’ll liberalize China. While one part of that was essentially opening our doors and our borders to Chinese citizens, to Chinese students, to Chinese companies, and the idea was that this would eventually help us and make China a partner.

The problem is if that fails, we are now more vulnerable and more exposed to the Chinese Communist Party than we ever were to the Soviet Union.

And so we have researchers at insensitive U.S. academic research institutes. We have Chinese apps, social media apps, that are transmitting data back to Beijing. We have Chinese farmland purchases near sensitive military installations. And so we have in many ways left ourselves exposed to the CCP in ways that we never were with the Soviet Union.

And part of this paper is about the need to recognize those vulnerabilities and recognize that this in-between engagement posture that we pursued for decades has essentially failed and there’s now a growing bipartisan consensus about that.

One of the first things we need to do is readjust the relationship with China to account for that reality and part of readjusting that is extracting these nefarious CCP influences from within the United States and protecting our people from the Communist Party.

Aschieris: One other part of the paper addresses the foundation of the victory plan. Can you talk more about this?

Smith: Yeah. Well, what we do is we call this a plan rather than a strategy. And so, it is a series of, the paper is broken down essentially into three sections.

The first section reviews the current state of the China-U.S. rivalry, and we explicitly call China an adversary in that section, and we look at how we got here and the comparative strengths and weaknesses of both countries.

The second section, which is essentially the heart of the plan, is a series of over 40 issue-specific, roughly one-page sections that cover numerous aspects of Chinese nefarious activities and the China-U.S. rivalry. Everything from, as you mentioned, land use, Chinese social media apps, to ways to protect the U.S. economy, ways to spur economic growth, the need for energy independence, the need to reform defense spending, the need to arm Taiwan and clear a backlog of what covers dozens of issues that fall under the China-U.S. relationship.

There’s also a section in there that talks about need for the U.S. to demonstrate leadership in the world. And so we take a tour of the globe and look at some of the key regions or multilateral groupings and look at what the United States has to do in partnership with allies to secure American interests in those parts of the world.

And so there are, as I said, over 100 specific policy recommendations throughout Section 2 to guide policymakers in the executive and legislative branches.

And the final section is a wrap-up summary of those recommendations as well as a look at how the U.S. government needs to organize itself and follow through to implement a plan like this that ultimately we hope will lead to victory.

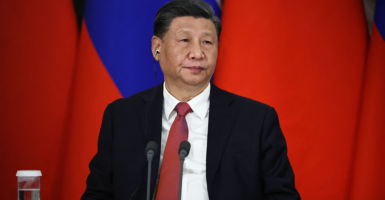

Aschieris: Yes, definitely. That is great. I will make sure to include a link to the full paper so our audience can take a look at that. And we’re having this conversation shortly after Chinese President Xi Jinping met with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Moscow. The two nations, according to CNBC, agreed to cooperate on different economic and business areas. How should the U.S. exercise global leadership with regard to this growing axis of evil?

Smith: Yeah, it is something we need to be concerned about. For a long time, I think, observers were willing to write off this growing China-Russia relationship and look at their history of animosity and territorial disputes and suggest that it was a limited tactical partnership that was eventually bound to fail. I think that bet was wrong.

And I think, particularly since 2014, when Russia invaded Crimea, and the West, led by the U.S., imposed a series of really crushing sanctions on Russia, they made a big, long-term strategic bet to turn away from Europe, to turn away from the West, and really embrace China and the China-Russia partnership.

And for the Chinese, they were able to get discounted energy, discounted arms, greater convergence at the United Nations Security Council, providing cover for each other. And they’ve been joined by their mutual animosity toward the U.S. and the West and the international order that the United States has helped to construct and lead post-World War II.

So that strategic partnership now is more entrenched than it’s ever been and I think is likely to continue for the foreseeable future.

Russia has essentially completely cut off all its access to the West and its ambitions of ever being a part of the West. And so this is a dyad that we’re going to have to grapple with for decades to come.

I guess, it’s maybe some consolation that Russia is very much the junior partner in this relationship, and I think it will continue to weaken in the years ahead.

Russia is losing people, its population is shrinking, its economy is shrinking. It’s been somewhat overshadowed by high energy prices over the past two years that have helped keep the Russian economy afloat. And when energy prices fall, we’re going to find that the rest of the Russian economy, the non-energy aspects of the Russian economy, have been absolutely devastated by this war and the Western sanctions that followed.

So I think Russia’s strategic position is weakening and that’s good for the United States, but it will continue to be a troublemaker in Europe and a valuable partner for our real adversary, which is China. And so we have to keep our eye on the ball.

Aschieris: I don’t think we can discuss China without talking about the role it plays in the U.S. fentanyl crisis. Can you walk us through some of the core concerns here and what action should be taken?

Smith: Yeah. So, it is a big concern. We now are looking at roughly 70,000 Americans dying every year from fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. In some communities across some demographics, it’s now the single biggest cause of death.

And where China comes into this is that the vast majority of fentanyl consumed in the U.S. comes from chemical precursors that originated in China. And some of that comes directly from China, most of it comes through the Mexican border.

So it’s not necessarily pre-made fentanyl shipped to the U.S. in a neat Chinese package, but the chemicals that are used to make fentanyl are imported into Mexico from China and then essentially made into drugs and brought over the border.

We have asked China repeatedly to crack down on the export of these chemicals and frankly, its response has been insufficient. And we need to make this a bigger priority in our relationship with the Chinese. It should be brought up in every diplomatic interaction we have with them.

And we need to let them know that this is deadly serious and that if we don’t feel sufficient action is being taken against the exporters of these precursors, we will continue to raise the temperature. We will impose sanctions and other economic costs on China for engaging in this trade and those sanctions will escalate every month or every year that this continues and there’s inaction from Beijing.

That’s the long answer. But we know it’s coming from China and we know the Chinese Communist Party leadership is not doing everything it can to stop this flow, and we need to change that.

Aschieris: Now, over the last few months, we’ve been hearing more about China’s threat to Taiwan and this potential invasion, especially after Russia’s invasion into Ukraine. From your perspective, what should the U.S. do to counter or diminish China’s threat to Taiwan?

Smith: Yeah. Great question. I think the first thing we need to do is clear a backlog of arms sales to Taiwan. We sell Taiwan advanced military hardware, and a number of important platforms that the Taiwanese have purchased have been backlogged, and this has been going on for years now. The war in Ukraine, I think, has made some of that backlog even worse, but this problem predates the Ukraine crisis.

And so there’s, frankly, a lot of things we need to do to increase deterrence, but the first thing we need to do is get Taiwan the weapons that it’s already purchased.

The second thing we need to do, I think, is help the Taiwanese to develop even better deterrence strategies and denial strategies and acquisitions. What can we do? What are the most effective military platforms that Taiwan could purchase and use in order to deny China if it decides to launch an invasion or at least to hold out long enough for the cavalry?

The Taiwanese have not always had the most effective or efficient strategies for how to defend the island in the opinion of many U.S. military planners and strategists. And so we need to work with them to craft, I would say, more effective plans and to get them, encourage them, incentivize them to purchase the most efficient military resources for denying China access to the island.

So we need to clear the weapons backlog, we need to improve their strategy, and we need to continue signaling to China that any move to invade the island would result in catastrophic consequences for China. And so we need to make sure that it’s understood in Beijing that any military adventure would be met with a swift and decisive response by the United States. So there’s other things we need to keep doing, but those are the top three, in my opinion.

Aschieris: Jeff, just before we go, I wanted to ask, what do you think the U.S., and maybe even here at The Heritage Foundation, that we’ve gotten wrong about China and the threat that it poses to our country and our way of life?

Smith: Well, [Heritage Foundation President Kevin] Roberts did an interview, I believe, yesterday, where he acknowledged that for many, many years and maybe even many decades, we as a country were naive about China. And he said, “I’m one of them. I personally was naive and I got it wrong, and I’m willing to admit and acknowledge that.”

I was also in the camp that for many years thought greater economic and political engagement with China was never going to produce a utopian Western democracy. But we would at least see continued movement toward selective political and economic opening. So not a full democracy, but maybe an expansion of local elections. Not a full market economy, but continued opening to greater trade and investment. And frankly, we simply got it wrong.

I don’t know that that was a pre-ordained conclusion. I don’t know that we all should have seen that this exact outcome would’ve happened because there were mixed signals.

Certainly in the 1990s and 2000s, it would be one step forward, two steps back, two steps sideways, one step back, three steps forward. But it’s very clear now. It has been clear, I would argue, since around 2008, 2009, the global financial crisis, but crystal clear since the rise of General Secretary Xi Jinping, that China is not moving in the direction of liberalization of any kind, not on human rights, not on economics, not on politics.

And so I think, as Dr. Roberts did, we should be humble and acknowledge that we did get it wrong. And now is time for a countrywide reassessment and reappraisal of the relationship. And it’s time to readjust and account for the fact that China is an adversary and our relationship with an adversarial China needs to look much different than it would have been with a China that was on the path to reform.

Aschieris: Well, Jeff, I wish we had more time to discuss, but that’s all the time we got for today. So thank you so much for joining us today. I really appreciate it.

Smith: Thank you.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email [email protected] and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the url or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.