Many COVID-19 restrictions and mandates have been rolled back, but the infrastructure remains in place, “ready and waiting for the next declared public health crisis,” Dr. Aaron Kheriaty says.

Kheriaty, a psychiatrist who directs the Bioethics and American Democracy program at the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, chose to speak out against the COVID-19 vaccine mandates, That decision cost him his job at the University of California, Irvine, School of Medicine.

Kheriaty says he is concerned that the “pretext of public health and safety has proven to be a good fulcrum, a good lever to get people to do things that otherwise they would be very reluctant to do.”

“It’s also been an occasion for the accumulation of power, mostly by the executive branch of government,” he says.

In his new book “The New Abnormal: The Rise of the Biomedical Security State,” Kheriaty details the ways in which governments past and present have used public health crises to gain power.

Kheriaty joins “The Daily Signal Podcast” to discuss how, unless placed in check, the government will use public health orders to further its own agenda, whether about COVID-19, climate change, or abortion.

Listen to the podcast below or read the lightly edited transcript:

Virginia Allen: Dr. Aaron Kheriaty is a psychiatrist and the director of the program in Bioethics and American Democracy at the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, D.C. He formally taught psychiatry at the University of California, Irvine, School of Medicine and was the director of the Medical Ethics program there, and was the chairman of the Ethics Committee at the California Department of State Hospitals. Today, Dr. Aaron Kheriaty joins us to discuss his new book “The New Abnormal: The Rise of the Biomedical Security State.” Dr. Kheriaty, welcome to the show.

Dr. Aaron Kheriaty: Thanks, Virginia. Great to be with you.

Allen: Well, your new book was written in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the title is “The New Abnormal: The Rise of the Biomedical Security State.” I want to begin by asking you to just define that term, biomedical security state. What do you mean by that?

Kheriaty: The biomedical security state is the public health infrastructure that we saw rolled out during COVID. It was 20 years, 25 years in the making, but at first was deployed and manifested publicly starting in March of 2020.

The biomedical security state is essentially the welding together of three things that used to be more or less distinct. The first is an increasingly militarized public health apparatus, and I can talk more later about what I mean by a militarized public health apparatus. That was welded to the use of digital technologies of surveillance and control.

This is the first epidemic or pandemic of the digital age. The first time we’ve had a major outbreak like this in a population where we had the technological ability to monitor the movements and the location and all kinds of other data and information about each individual in the population through smartphone technology.

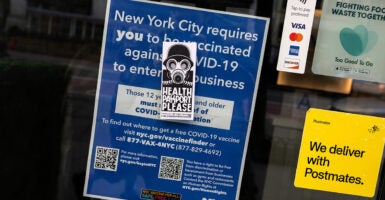

The first iPhone was released in 2007 and in 2020 we saw the deployment of digital technologies for surveillance and control of entire populations as a novel method of trying to control a respiratory virus. So, we could think of things like the vaccine passport, the QR code on your phone, that you have to show to get on a plane, get on a train, go to a restaurant or a public event, or even get back into your own country of origin. That’s an obvious use of these technologies.

Less well known is the fact that many Western, supposedly free democratic societies utilized unauthorized surveillance, basically extracting track and trace data from smartphones without the knowledge or consent of the population.

This happened legislatively in Israel during the omicron wave, where they passed emergency legislation to allow the Shin Bet, basically their version of the FBI, to do this. That was at least done publicly by people who could be voted out of office.

We found out a couple of months after that that Canada had been doing the same thing, even though [Prime Minister] Justin Trudeau had promised the Canadian people that this would not be done. And the Canadian Public Health Agency admitted that it was going to continue extracting data from smartphones to monitor movements and who was associating with whom on into at least 2026 and to use this for public health applications beyond COVID.

Then, in May of last year, Vice broke the story that the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] had been doing the same thing, again, without the public’s notification or consent, monitoring how many people were gathering at a church or how many people were gathering at a school.

Supposedly, this data was anonymized, but there were some researchers from Princeton that showed that with only four data points, very easily, the particular number in that dataset could be linked to a specific identifiable individual.

Those are just a few examples, I have many more in the book of the deployment of technologies of mass surveillance in order to monitor and nudge and control people’s behavior at a very micro level.

Then these two elements—the increasingly militarized public health apparatus, the digital technologies of surveillance and control—are backed up by the third element, which is the police powers of the state that were used to enforce public health directives passed non-legislatively on an emergency basis, more or less using emergency executive powers by governors or by the president and their appointees, the unelected public health bureaucrats.

We could think, for example, of the invocation of the Emergencies Act in Canada by Trudeau for the first time in Canadian history, under which he not only removed the truckers protest in Ottawa, a peaceable protest—forcibly removed them from the city using a militarized police force that went in and roughed up the truckers on their way out—but even more than that, he used that to freeze the bank accounts of the truckers with the cooperation of private banks that willingly acceded to this demand and even freeze the bank accounts of people who had given money to the truckers.

So, imagine giving 50 bucks to the Freedom Convoy in Canada and then going to the ATM the next day and not being able to withdraw money from your bank account because you were supporting a peaceful public gathering, protesting the government’s preferred pandemic policies.

What I argue in the book—and the book is primarily not a retrospective on what happened during COVID, it’s a forward-looking book, saying, even though a lot of these individual policies, a vaccine mandate here or social distancing rules there, have been rolled back at this point, the entire infrastructure that I just described is still in place and ready and waiting for the next declared public health crisis.

In a sense, if we do not start to recognize the way in which emergency powers were deployed and this biomedical security model of governance was deployed during the pandemic, we’re going to see more of this in the future.

With the implementation of lockdowns in March of 2020, I argue that we saw not just the rollout of a novel method for trying to control a respiratory virus that had never been tried before and had no empirical data supporting its use, we saw, in fact, a new paradigm of governance, one that sort of entails jumping from one declared crisis to the next, which is why the plausibility of the COVID crisis has waned in the public’s consciousness.

We’ve seen efforts to create a new public health crisis out of a novel virus. The monkeypox scare is an example of that or the tripledemic with, we’re going to have influenza and COVID and RSV this winter, which turned out to be a nothingburger. But we’ve also seen efforts to reframe other issues as public health issues.

We’ve seen, really, over the last five years, even before the pandemic started, efforts to frame climate change from what used to be considered an environmental or an ecological issue to now it’s framed in terms of its harms to population health. It’s a public health issue. If you look at all the headlines on climate change over the last four or five years, you’ll see this pattern. Now we have voices calling for rolling lockdowns and other sort of biosecurity measures to deal with the climate crisis.

The biomedical security state is, I argue in the book, is a threat to liberal democracies and a threat to the freedoms that we have enjoyed, constitutional freedoms that we’ve enjoyed in the United States and in other Western nations. That’s why I think we have to recognize that COVID, in a sense, was just the beginning. And we need to look forward and see, “OK, what are the next steps in the process of implementing this new paradigm of governance? And how do we stand up against those so we don’t continue unwittingly to relinquish our freedoms and our liberties?”

Allen: Because what it sounds like you’re saying is that when the government finds a way to fit an issue into the medical box, there’s a lot of powers that come—

Kheriaty: Exactly.

Allen: … with that. Maybe even the American people or just people in general, they’re a little bit more willing to maybe cede some of those freedoms because, obviously, we all want to be healthy, we all want to protect our neighbor, so there’s that willingness.

I would even be curious to get your thoughts on just this week, we’ve seen that the Biden administration announced a possible public health emergency order related to abortion. Is this sort of the kind of thing that you’re talking about moving forward that maybe after COVID we could see an increase of?

Kheriaty: I think that’s exactly right. The pretext of public health and safety has proven to be a good fulcrum, a good lever to get people to do things that otherwise they would be very reluctant to do. It’s also been an occasion for the accumulation of power, mostly by the executive branch of government.

The president gains 128 additional extra constitutional powers during a declared state of emergency. One of the reasons that the Biden administration has been reluctant to declare the pandemic over is they know that if the pandemic is over, then the public health emergency that’s been declared at the federal level also has to be sundowned.

I think they announced the other day that that’s going to happen in a hundred days or something like that. So, how you can predict three or four months in advance that an emergency will be over at that point is an interesting epistemological question.

But Biden announced coming into the midterms that the pandemic was over, which was of course true, it’s been over for quite some time. The virus is endemic. You’re going to get a seasonal rise and fall of cases, but the criteria for an epidemic or a pandemic is long since passed. Obviously, it would’ve been politically advantageous for him to announce that going into the midterms, a sort of victory over COVID while he was in power.

But immediately his advisers panicked and said, “No, no, no. You can’t say that.” The reason they panicked was precisely this. They knew that if his administration admitted the truth about COVID, that they would have to relinquish those emergency powers, which have allowed for access to spending money, access to deploying the military infrastructure, the intelligence infrastructure, communications, and so forth, all in the service supposedly of public health and safety.

The same thing has happened at the state level. We have a situation in which governors and presidents can unilaterally declare an emergency, accrue the powers under that emergency declaration, and then unilaterally decide when to relinquish those powers. This is a bad setup if there are no judicial or legislative checks or balances on that system.

This is precisely why I think we’re seeing these efforts, like the one that you just mentioned, to declare other issues, whether it’s abortion or climate change or—racism was declared a public health crisis during the lockdowns of 2020, you might remember, when there was the large public protests that, in many cities, turned into violent riots associated with the Black Lives Matter movement and the George Floyd killing.

There was a group of about 1,200 public health academics, I guess, and bureaucrats that wrote a letter declaring that these gatherings were OK, even though everyone else was supposed to be staying at home and socially distancing, because racism was a public health crisis that apparently trumped, at that point, the public health crisis of COVID, that was requiring emergency lockdowns and school closures.

So, this pattern has been happening for at least three years, and I think in the case of climate change, for about five years. And we’re going to continue to see the pretext of public health and safety that supposedly requires a state of emergency in order to advance policies that would’ve been impossible to do through the usual legislative mechanisms.

Allen: You do such a nice job in the book of looking back at history and some of the roots, really, of this kind of thinking, where it’s come from. You also discussed the Nuremberg Code. What is that? First, if you would just lay that out for us, and then why is it significant for us today to be considering that and remembering it for this moment in history?

Kheriaty: The Nuremberg Code is a document that I actually encourage our listeners to go look up and read. It’s a short document. It’s not complicated. It’s about a page or two long.

The Nuremberg Code was developed following the Nuremberg trials after World War II, where an international tribunal led by the United States, but including other Allied powers, tried the Nazi war criminals, which included, of course, military war criminals and government officials, but also included a dozen Nazi physicians who had conducted gruesome experiments on death camp prisoners without those prisoners’ consent. Half of those doctors were convicted and sentenced, in fact, to death, and a handful of them actually hanged for those crimes against humanity.

Following that, the Nuremberg Code was developed to try to prevent those kinds of abuses and atrocities of patients and research subjects in the future.

The very first principle of the Nuremberg Code is the doctrine of informed consent, that in order to intervene on an individual medically, or in order to enroll an individual in a medical experiment, you can only do so with the individual’s full knowledge of what they’re agreeing to and uncoerced consent.

So, every adult of sound mind has the right to decide what medical interventions they will accept or will decline after being given adequate information about the risks, the benefits, and the alternatives to that treatment. They have the right to make those decisions on behalf of their own children, who are not yet old enough and cognitively mature enough to give consent.

That was the central doctrine of 20th-century medical ethics. The Nuremberg Code doesn’t have the binding force of law, but it influenced the laws in virtually every Western nation, certainly, when it comes to research on human subjects and when it comes to the ethical practice of medicine.

One of my concerns during the pandemic was precisely that this idea of informed consent was being steamrolled by lack of adequate information about the interventions that were being proposed, first of all, but also about coercive measures like vaccine mandates that were deployed to force people who were hesitant to receive a particular medical intervention.

That’s sort of the hill that I ended up dying on and sacrificing my career in academic medicine on, because I was opposing the University of California’s vaccine mandate, where I had been a full professor in the School of Medicine there for my entire career, 15 years. I also directed the Medical Ethics program there. I challenged the university’s vaccine mandate in federal court on constitutional grounds. As a consequence of that, the university fired me. Essentially, what I believed myself to be doing there was defending this idea of informed consent.

I think the Nuremberg Code is a landmark document of 20th-century political society and certainly 20th-century medical ethics that we would do well not to forget.

Anytime you make an analogy to the Third Reich, people tend to freak out. I want to be clear, and just a caveat here, I’m not comparing either the current or the previous administration to Hitler’s Nazi regime. But it also remains an undeniable historical fact, just to circle back to our earlier theme, that the Nazis governed for virtually their entirety of their time and power under Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution, which permitted the suspension of German laws during a time of emergency. This supposed public and public health emergency lasted, in that case, for 12 years.

So, we can ask, how did Hitler go from the legitimately appointed chancellor of Germany to a totalitarian dictator of Germany? Well, that legal mechanism of the state of exception or state of emergency was deployed by his regime precisely in order to accrue total power.

So, there are historical analogies. History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes. So, there are historical analogies, that’s one from the 20th century, there are others that I cite in the book for this misuse of emergency powers to basically suspend constitutional rights.

The Nazis never overturned or did away with the Weimar Republic’s constitution. They just bracketed it. They just held it in obeyance indefinitely and did an end run around it through this legal mechanism of a declared state of emergency.

So, I think we have to be very, very careful about the use of emergency powers and the framing of all kinds of social and political and moral issues as public health issues because we’ve seen where that can take us, in the past, when we allow an executive power to unilaterally accrue additional powers and keep those powers far longer than would be warranted by any objective analysis of the state, whether it’s a virus or an external threat, like the threat of war.

It’s precisely during these kinds of crises that we need to adhere more firmly to our constitutional principles of free speech and freedom of religion and freedom of association and a free press that’s not subjected to government censorship, because [in] those crisis situations of war and epidemic and so forth … we’re most strongly tempted to make an exception and to do an end run around human rights and constitutional liberties.

Allen: And Dr. Kheriaty, as you mentioned, your decision to really speak out on this issue and ultimately stand against the vaccine mandate at your former employer, the University of California, ultimately ended up costing you your job. Were there other colleagues in your profession in the field of medicine, the field of academia, who were raising the concerns that we’re talking about right now about the abuses of power that were happening under COVID-19?

Kheriaty: Certainly there were quite a few doctors and other health professionals and scientists who were raising concerns about specific pandemic policies. There are many doctors now, for example, raising concerns about the safety and efficacy of the mRNA vaccines that were deployed during the pandemic.

I can think of my colleague Dr. Aseem Malhotra, a cardiologist in Great Britain, who’s now very, very concerned, calling for a halt to the mass vaccination program with these vaccines, out of concerns for the cardiac harms, which he believes are more common than our public health agencies have admitted. Others, like my friend Dr. Peter McCullough and Dr. Robert Malone, have raised questions about the use of these vaccines as well.

There’s been a lot of epidemiologists and public health experts who have raised questions about lockdowns and have pointed out that, No. 1, lockdowns failed to achieve their purpose, their public health purpose, of slowing or stopping the spread of the virus, and that lockdowns and school closures have instead done enormous collateral harms.

I think of Jay Bhattacharya, my colleague at Stanford; Martin Kulldorff, my colleague at the Brownstone Institute; two of the signatories of the Great Barrington Declaration, who raised these concerns starting back in 2020.

So, I think we’ve seen a fair amount of critique of these policies. Unfortunately, we now know that many of those voices were suppressed or silenced, not only through social media censorship, but through social media censorship at the behest of the government. That’s one of the reasons why Jay and Martin and I are among the private plaintiffs challenging the government censorship regime in the Missouri v. Biden lawsuit.

But I don’t see a lot of people, there have been a few, but not as many, looking at some of the social and political issues that I’m talking about here. Giorgio Agamben, a philosopher from Italy, has written a lot about the issue of the state of emergency, state of exception. A scholar named Simon Elmer has written a book called “The Road to Fascism,” which digs into a lot of the same themes from a somewhat different angle, but a lot of the same themes that I raise in “The New Abnormal.”

Here and there are some critics of the sort of sociopolitical elements of what we’ve seen during the pandemic. Others have written about the economic forces that were at work during the pandemic, nudging us toward policies that were economically advantageous for Big Tech and other global elites, but harmful to the working class and the middle class. But my book is really an attempt to synthesize these concerns and paint a sort of big picture understanding of, first of all, what happened to us, and then, second of all, where’s this biomedical security regime going to take us next? What are the next steps in its implementation?

Allen: That understanding I think is so critical if we have hope of change and course-correcting.

Kheriaty: That’s right. Yeah.

Allen: I know that you wrote the book, obviously, not just to share a lot of bad news, but as really a signal to Americans and to society as a whole to say, “Hey, we need to be aware of what’s really happening here.” For all of our listeners, I encourage you to pick up a copy of the book “The New Abnormal: The Rise of the Biomedical Security State” by Dr. Aaron Kheriaty. Dr. Kheriaty, I just really thank you for your time today, for joining us.

Kheriaty: Thanks, Virginia. I enjoyed the conversation very much.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email [email protected] and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the url or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.