The game’s afoot on the legal definition of “sex.”

What was once a commonsense understanding of “sex” as meaning the biological distinctions between male and female has—under recent leftist claims that sex includes “gender identity”—become a flashpoint for the culture wars and clogged the federal courts.

Parents, legislators, and educators across the country are navigating a complex morass of state and federal laws and regulations.

But a federal judge in West Virginia delivered some good news on the definition of “sex” last week.

In another stinging defeat for the Biden administration’s woke agenda and its purveyors at the American Civil Liberties Union, U.S. District Judge Joseph Goodwin granted summary judgment (judgment entered by a court for one party and against another without a full trial) to the state of West Virginia on Friday on its Save Women’s Sports bill in B.P.J. v. W. Va. State Bd. of Ed.

Under the law, all biological males—including those who identify as transgender “girls”—are ineligible for participation on girls sports teams.

The ACLU and its West Virginia chapter had filed the lawsuit in 2021 on behalf of an 11-year-old transgender girl—a biological boy—who had hoped to compete in middle school cross-country in Harrison County.

The question before the court was whether the legislature’s chosen definition of “girl” and “woman” in its sports law was constitutionally permissible.

The judge found that it was.

“While some females may be able to outperform some males, it is generally accepted that, on average, males outperform females athletically because of inherent physical differences between the sexes,” Goodwin wrote.

As the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals did in Adams v. School Board of St. Johns County, Goodwin used an “intermediate” standard of review. The Supreme Court has prescribed this standard for legislative distinctions that are based on biological sex; it is lower than “strict scrutiny,” which almost always results in a law being invalidated, but higher than “rational basis,” which nearly always results in a law being upheld.

To satisfy intermediate scrutiny, the sports law had to (1) advance an important governmental objective; and (2) be substantially related to that objective.

The ACLU argued that when it passed the sports law, the legislature acted with the intention of discriminating against transgender children.

Goodwin rejected that argument and concluded that “[t]he legislature’s definition of ‘girl’ as being based on ‘biological sex’ is substantially related to the important government interest of providing equal athletic opportunities for females.”

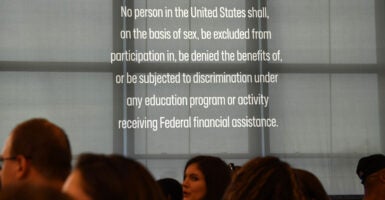

Goodwin also rejected the plaintiff’s claim that the state law violated Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, a 50-year-old civil rights law that prevents discrimination in education on the basis of sex, which feminists of the day considered a triumph.

Goodwin described what the ACLU had to prove in order to succeed:

To succeed on a Title IX claim, a plaintiff must prove that she was (1) excluded from an educational program on the basis of sex; (2) that the educational institution was receiving federal financial assistance at the time; and (3) that ‘improper discrimination caused [her] harm.’ … In the Title IX context, discrimination ‘mean[s] treating [an] individual worse than others who are similarly situated … .

Title IX permits sex-separate athletic teams, where selection for such teams is based upon competitive skill or the activity involved is a contact sport.

Goodwin concluded that the ACLU failed to meet that burden, and that while Title IX does not define “sex,” the term as used in that law was in the biological sense, because its very purpose was to promote equality between the sexes.

Goodwin noted that transgender girls are biologically male, and that biological males were not being excluded from school sports. Rather, they could always try out for the boys teams, regardless of how they expressed their gender identity.

Recognizing that the administration’s attempts to redefine sex are suffering some notable legal defeats, the U.S. Department of Education recently issued a notice of proposed rule-making in the Federal Register, indicating that it intends to make a new rule on Title IX.

That rule, however, in contrast to the Title IX rule announced last summer (which, as I’ve written, is full of errors), will deal only with transgender participation in school sports.

And while the Education Department has indicated it intends to publish the Title IX sports rule this May, the sports issue was already a part of the previous rule it proposed.

It’s no wonder the dialogue on trans athletes in scholastic sports has intensified.

Most readers will be familiar with the story of Lia Thomas, the University of Pennsylvania swimmer who represents himself to be female and stole the NCAA Division I Championship last March from his closest female competitor.

Now, Iszak Henig, a transgender male (biological female) has joined Yale’s men’s swimming team after concluding last year’s season as an All-American swimmer on the women’s team. Henig has taken hormones for eight months. In a recent meet in November, she finished (some might argue, predictably) in 79th place out of 83 swimmers.

Only time will tell whether the U.S. Supreme Court will choose to get involved and resolve the question of whether “sex” within the education context means biological distinctions between males and females.

With a split among two federal circuits on the same constitutional and statutory questions on “sex” (one in the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals and one in the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, as I’ve written about here), the high court has an opportunity to resolve the issue once and for all.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email [email protected] and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the url or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.