First of two articles

Representatives from some 190 countries will meet in Egypt for two weeks starting Nov. 6 to “[deliver] for people and the planet” at COP27, the U.N. Conference of the Parties annual summit on climate change policy.

The predominant message at these climate conferences is one of “catastrophic” global warming necessitating policies to reduce anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions drastically.

COP27 in Egypt will likely be no different, even though last year’s conference in Glasgow, Scotland, was heralded by the United Nations and the popular press as “one minute to midnight,” “literally the last chance,” with “no more time to hang back,” and any number of other “emergency mode” warnings to catalyze “maximum ambition—from all countries on all fronts.”

Member nations of the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change have met for these Conferences of the Parties since the first one in Berlin in 1995. These summits aim to establish a common understanding of global warming as an emergency, agree upon broad policy objectives, and enforce the Paris Agreement of 2015.

During the 2015 Paris meetings, governments agreed to “reach global peaking of greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible … and to undertake rapid reductions thereafter” in a bid to limit global temperature increases to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. To that end, more than 40 countries—including the United States, Great Britain, and members of the European Union—have established policies attempting to force massive transitions of their energy sectors and economies to “net-zero” greenhouse gas emissions by midcentury.

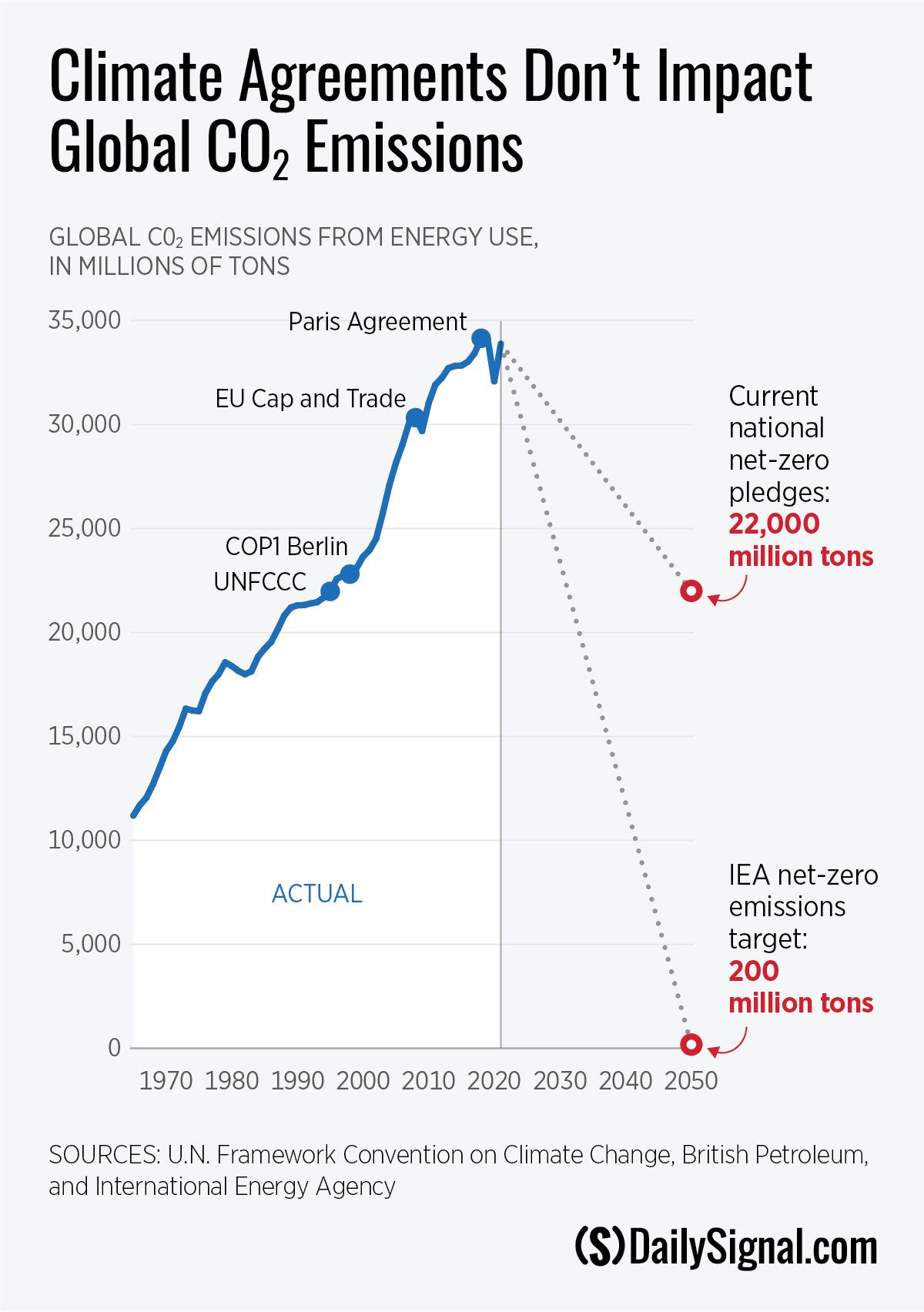

Despite clear success in defining and propagating a narrative of alarm in the media and in politics, and the general awareness of Western populations, it’s fair to say that nearly three decades of COP meetings have not accomplished much in the way of their stated objective to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions globally.

Setting aside relevant questions about the degree to which anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions drive warming, global emissions have only continued to increase since the first COP at Berlin in 1995.

To put the Paris Agreement goals in perspective, carbon dioxide emissions from energy production and use (the overwhelming majority of man-made emissions) declined more than 5% in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and government responses to it. Those caused a historic retraction in economic activity and mobility, and consequently, in demand for oil, natural gas, and coal.

Despite the recession, global concentrations of greenhouse gases still increased in 2020.

It appears that global carbon dioxide emissions in 2022 will again exceed pre-pandemic levels. The U.N. estimates that greenhouse gas emissions will continue to rise even if countries fully meet their Paris Agreement commitments.

The U.N. and the World Meteorological Society estimate that countries’ pledged emissions reductions “[need] to be … seven times higher” to meet the Paris Agreement goal. A report from the meteorological society concludes: “We are still nowhere near the scale and pace of emission reductions required.”

Government representatives who supported the radical changes heralded at COPs and enshrined in the Paris Agreement have tried to be optimistic as COP27 begins. They emphasize the net-zero emissions policies and exorbitant spending announced by many Western governments to inhibit access to conventional energy and force a transition to alternatives.

It’s one thing to intend to do something, but another entirely to actually do it. A radical energy transition is far from a foregone conclusion.

For example, the International Energy Agency’s annual “Tracking Clean Energy Progress” report considers only two components (electric car sales and lighting) of 55 technology and infrastructure components “on track” for a net-zero energy transition.

Yet even with electric car sales—one of those “on track” components—political aspirations and timetables are already starting to hit the road of reality. The International Energy Agency estimates that politicians’ aspirations for EV deployment under the Paris Agreement imply a thirtyfold increase in demand for minerals used in EV batteries by 2040.

Baked into many governments’ net-zero policies are similar leaping assumptions about the technological readiness, affordability, and deployment of adequate replacements for conventional fuels. They presume massive market shifts in multitrillion-dollar sectors of global economic activity as large as the transportation, industrial, and petrochemical sectors—free of political constraints and trade-offs.

Net-zero transition plans are more appropriately understood as a policy “gamble” that replacement energy technologies will be sufficiently available on political timelines. That gamble shows no sign of paying off.

Despite the aspirational policies attempting to define a transition away from conventional fuels, actions speak louder than words. Countries are showing every day that they are more interested in affordable energy than in paying a green premium. That’s proving particularly true in light of the energy-price crisis, whether considering China’s interest in buying Russian oil, or climate warrior Germany’s decision to hold onto coal.

If the purpose of Conference of Party summits is to instigate rapid reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, they have failed.

Where they have been successful is in giving politicians leeway under the cloak of supposed impending catastrophe to centrally plan the energy sector and entire economies. They have also been successful in absolving those politicians of accountability for the consequences of those policies.

But with a global energy crisis in large part created and inflamed by the net-zero policies championed at these summits and enshrined in the Paris Agreement, even that “success” may (finally) be wearing thin.

Tomorrow: In Part 2, see why COP27 in Egypt is still likely destined for failure even if the net-zero policy commitments made by Western governments were on track. The demand for reliable, affordable energy is only increasing globally—and for good reason.

This commentary was corrected Dec. 13, 2022, to say that global concentrations of greenhouse gases, not emissions, increased in 2020.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email [email protected] and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the url or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.

One Reply to “Why International Climate Summits Are Doomed to Fail, Part 1: Aspirations Untethered From Reality”