RICHMOND—Americans who are fighting the left’s attempts to restrict our liberties, destroy our culture, and manipulate our society using the imperious power of the government sometimes may forget that we’ve been struggling to preserve our liberty and freedoms from overbearing governments since the beginning of our nation.

But my wife and I got a stirring and inspiring reminder this past Sunday at St. John’s Church, the oldest church in Virginia’s capital, Richmond.

Built in 1741 on a high hill with a sweeping view of the James River, St. John’s is still a functioning church today. St. John’s is the place where American patriot Patrick Henry gave one of the most famous speeches in history, concluding with the immortal words, “Give me liberty, or give me death.”

Nearly 250 years later, we bemoan that government has sunk its claws into almost every aspect of our lives, including our families, our professions, and our businesses.

Henry’s 1775 speech, and his defiance, helped inspire the colonists who were rebelling against the all-powerful British monarchy that had sunk its tightening claws into almost every aspect of their lives, too.

As related by the St. John’s Foundation, which is dedicated to preserving the church in Richmond: “American soldiers of the Revolutionary War marched into battle carrying ‘Liberty or Death’ flags.”

Patrick Henry’s words have inspired people around the world ever since he first spoke them.

That includes the brave protesters who gathered in Tiananmen Square in 1989 to take on the despotic, tyrannical Chinese government—a government that has gotten only worse since then, repressing its citizens and threatening the world. Many of those Chinese protesters carried signs quoting Henry’s words over 200 years after he appeared at St. John’s Church on March 23, 1775, during the second Virginia convention.

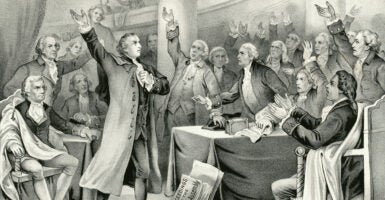

My wife and I were at St. John’s for a recreation of the crucial part of that convention—the debate over what to do about Britain’s treatment of the colonies.

The first Continental Congress met in Philadelphia in October of 1774. The British government had imposed a series of taxes and restrictions on Americans, including the Stamp Act, Sugar Act, Townshend Acts, and Intolerable Acts, which the colonists believed violated their rights and their idea of self-government. These acts led to many acts of defiance, including the Boston Tea Party on Dec. 16, 1773, which resulted in the British navy closing Boston as a port and blockading it in March 1774.

On March 23, 1775, Williamsburg was still the capital of the Virginia colony. The second Virginia convention met in Richmond, however, because the 50 miles between the two towns was considered sufficient to prevent the royal governor, Lord Dunmore, from sending troops to arrest the attendees.

Delegates included several eventual signers of the Declaration of Independence, such as Benjamin Harrison V, Richard Henry Lee, and Thomas Nelson Jr. The convention was presided over by Peyton Randolph, also the first and third president of the Continental Congress. The three most prominent attendees—Henry, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington—often have been referred to as the voice, the pen, and the sword of the American Revolution.

The debate that led to Henry’s fiery oration was over a resolution he introduced to go forward with Virginians arming and organizing to protect themselves from the tyranny of the royal government and military occupation. Henry’s resolution said that “a well-regulated militia is the natural strength and only security of a free government” and was “at this time, peculiarly necessary for the protection and defense of the country.”

If those words sound familiar, they should. Much of that same language ended up in the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Henry called for Virginia to “be immediately put into a state of defense and that a committee be named … to prepare a plan for embodying, arming, and disciplining such a number of men as may be sufficient for that purpose.”

Lee seconded Henry’s resolution. Jefferson and Washington were among delegates supporting it. Washington said that as a soldier, he believed “in being prepared,” a simple but straightforward proposition that should be the main driving force of our military policy even today.

Harrison voiced opposition, though, saying Henry’s resolution was “rash and inexpedient” and that Virginians “should do nothing hastily, offer no provocation.”

Edmund Pendleton agreed, arguing that the colony should “proceed slowly before rushing Virginia into war,” while Robert Carter Nicholas said Henry was being “hasty, rash, and unreasonable.”

But Henry was having none of it. Americans should take heart from him if they have been silenced by school boards, university administrators, liberal media pundits, social media censors, and others who are trying to restrict any speech that doesn’t fit within the political orthodoxy of the radical left because it is “offensive.”

“Should I keep back my opinions at such a time through fear of giving offense,” Henry said, “I should consider myself guilty of treason toward my country and of an act of disloyalty toward the majesty of Heaven, which I revere above all earthly kings.”

The forces arrayed against us today, including Hollywood, social media and news platforms, academic institutions, corporations such as Disney, and government bureaucracies, may seem overwhelming at times. But Henry and his fellow Americans faced the world’s largest, strongest empire and military power.

As Henry said:

They tell us, sir, that we are weak—unable to cope with so formidable an adversary. But when shall we be stronger? Will it be the next week, or the next? Will it be when we are totally disarmed, and when a British guard shall be stationed in every house? Shall we gather strength by irresolution and inaction? Shall we acquire the means of effectual resistance by lying supinely on our backs, and hugging the delusive phantom of Hope, until our enemies shall have bound us hand and foot?

Sir, we are not weak, if we make a proper use of those means which the God of nature hath placed in our power. … The battle, sir, is not to the strong alone; it is to the vigilant, the active, the brave. …

Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!

Unlike Patrick Henry, we’re not facing an armed oppressor (at least domestically). But we are facing a formidable array of forces internally that want to abolish our precious heritage of individual freedom and liberty, rewrite our history with their propaganda, pollute the minds of our children, and transform us into their version of a socialist “paradise” (everyone else’s version of a nightmare).

Just sitting inside the beautiful church in which the Virginia convention met in 1775, where Henry gave his passionate speech, was moving. But to hear the debate and his speech reenacted was, frankly, reinvigorating.

The experience renewed my energy and my spirit to work toward what the overwhelming majority of Americans want. It’s what my Heritage Foundation colleagues and I work at every day: building and preserving an America where freedom, opportunity, prosperity, and civil society flourish.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email [email protected] and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the URL or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.