Editor’s note: Rev. Dean Nelson, a staunch defender of the unborn, passed away Saturday at the age of 55.

‘It is with profound gratitude for his life that we mourn the loss of our Executive Director, Reverend Dean Nelson,” Human Coalition wrote on X, formerly Twitter, Sunday. “He has gone home to his eternal reward in the loving arms of Our Father. We pray for the grace to carry on the work that bore his name. Rest in peace, dear brother.”

Nelson’s work at Human Coalition was aimed at advancing a culture of life across America.

He died after battling cancer and leaves behind a wife and three children.

“We are heartbroken to lose him so soon, but so so grateful to be his family,” his wife Julia Nelson wrote in a statement shared on X.

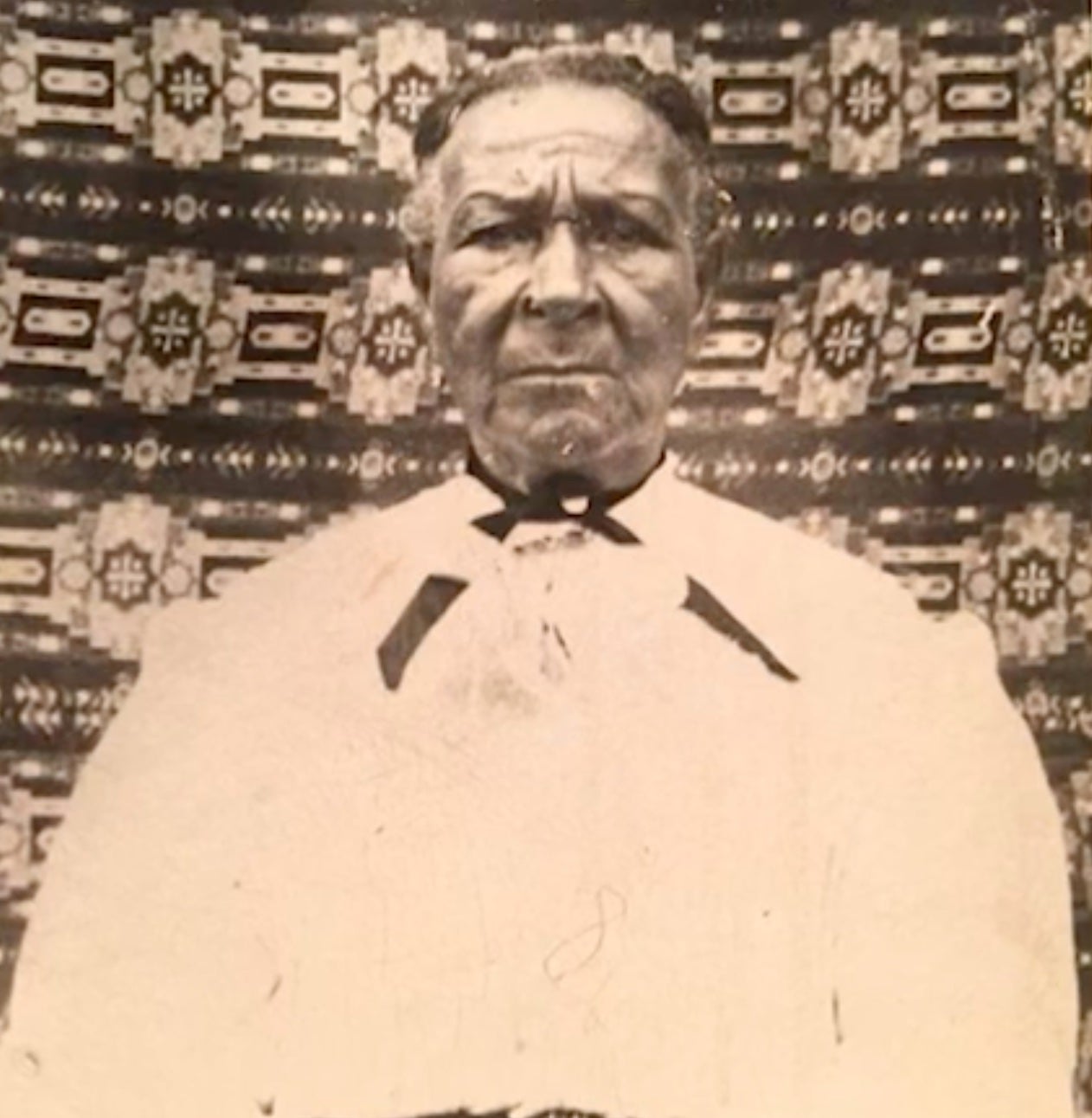

Sitting in the small Baptist church he grew up attending, Dean Nelson recalls stories of his family’s history, including those of his great-great-grandmother, Easter Nelson.

Easter Nelson “was a slave, but lived during the time the Emancipation Proclamation took place,” he tells The Daily Signal.

“Hearing stories [from] my dad and my grandparents about Great-Great-Grandma Easter [was] powerful, knowing that … she was someone who came out of slavery,” Nelson says.

Nelson, who today serves as chairman of The Frederick Douglass Foundation and vice president of government relations for the pro-life nonprofit Human Coalition, never met his great-great-grandmother.

But he says she would be proud to know that her descendants went on to find success, earning degrees from colleges such as Harvard and the University of Virginia, which blacks couldn’t attend until the 1950s.

Growing up in the 1970s in Marshall, Virginia—50 miles west of Washington—he was aware of racism, Nelson says, but his family was careful not to allow the issue of race to overwhelm them.

“There was a restaurant actually in our town, even in the ’80s, that didn’t welcome African Americans,” Nelson says. “And most of us knew Roy McKoy had this restaurant, but who wants to eat at a restaurant where you’re not wanted?”

“My parents taught us not to be overly impacted by conditions of racism that might’ve been around us,” he recalls.

Nelson says he doesn’t remember “hearing my parents or my grandparents ever say a negative word about a white person, despite the fact that my parents went to a segregated high school.”

That high school was called simply Number 18 School.

In fact, Nelson says, his parents often talked about opportunity, “rather than emphasizing the challenges that were around us.”

When it came time for Nelson to leave his small town for university, he says, the family values he was raised with were challenged.

After his first year at Howard University in Washington and before he transferred to the University of Virginia, Nelson says, he returned to Marshall “looking differently at white people, thinking that I was now better than them because of what they had done.”

But as he got older, Nelson recalls, he became “more intellectually honest about race and those situations within our culture.”

Studying history played a significant role in Nelson’s life, enabling him to process the dark parts of America’s past in a way he could not when younger.

“I never knew that there was a Virginian by the name of Robert Carter,” Nelson says. “Because of a religious conversion, Robert Carter overcame slavery by emancipating 500 slaves during his lifetime.”

Carter’s story, he says, became an example to him that “should be told in our history, not to sugarcoat the realities of racism, but to look and to see that [people], particularly people of faith, have embraced their better angels, so to speak, and overcome.”

No one has influenced Nelson’s own views of patriotism and faith more than the 19th-century American abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass, he says.

“Frederick Douglass, as a person of faith, didn’t just talk about his faith,” Nelson says, and “literally being able to forgive his slave master for enslaving him was to me the most profound act of forgiveness that could be done.”

In 1877, a free Douglass met with Thomas Auld, his former slave owner. Auld’s health was failing and the two reportedly wept as they discussed the past before parting ways cordially.

For any culture to move forward, “there has to be an element of forgiveness,” Nelson says, adding:

Forgiveness means, No. 1, acknowledging that there is something that is wrong that took place. And I think that the message of forgiveness is [that it is] healthy for an individual to be able to forgive. Because if you don’t, you will hold and harbor those resentments, and it’s only going to hurt you ultimately in the long run.

The Gospel message is empowering, “and that was the message that empowered Frederick Douglass,” Nelson says. “That was the message that empowered my great-great-grandma Easter.”

“It is a message of not forgetting about the sin of slavery, not sugarcoating the truth, [and] it is a message that you can acknowledge the past, but we can also acknowledge how bright our future can be if we’re willing to forgive and if we’re willing to embrace a better future for tomorrow.”

Editor’s note: This article has been corrected to reflect the schoolhouse pictured was a grammar school, and to clarify that some of Easter Nelson’s descendants went to colleges such as Harvard University, but Dean Nelson did not attend Harvard University.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email [email protected] and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the url or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.