While working to restore wildlife and plant habitats, a federally chartered conservation foundation pays lavish salaries to officers at the expense of environmental initiatives that are central to its mission, policy analysts and former employees say.

Compensation figures in Form 990 tax records prepared for the IRS ought to raise questions about the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s internal financial practices and the potential impact on conservation programs, a former employee told The Daily Signal in a phone interview.

Top officials, including Jeff Trandahl, the foundation’s executive director and CEO, receive annual compensation packages that appear to be “out of proportion” with those at other nonprofit conservation groups, said Alex Echols, who was the foundation’s deputy policy director from 1995 to 2000.

The Daily Signal depends on the support of readers like you. Donate now

Trandahl received $1.29 million in annual compensation in 2018 alone, according to the most recent available Form 990 tax records. By comparison, CEOs with other nonprofit conservation groups fell well short of Trandahl’s salary in recent years.

In 2017, Sierra Club Executive Director Dan Chu was paid $238,000 and American Forest Foundation President and CEO Thomas D. Martin made $386,560. In 2018, then-Natural Resources Defense Council President Rhea Suh made $543,741 and then-National Audubon Society CEO David Yarnold made $676,306.

“Donors to an outfit like the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation will eventually look at executive compensation, and if it’s out of line it causes them some concern and they will ask why the compensation levels are greater than they are for peer organizations,” Echols said in the interview with The Daily Signal. “I don’t know if there is anything untoward with NFWF, but the fact that the salaries are as high as they are does raise some questions.”

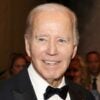

Trandahl, a Republican, worked on Capitol Hill for 23 years, serving as clerk for the House of Representatives from 1998 to 2005 before joining the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation as CEO and executive director in November 2005. The House clerk, elected every two years when the House organizes for a new Congress, serves as the chamber’s chief record keeper.

A 2018 report from the Congressional Research Service, more than 12 years after Trandahl left the post, put the clerk’s salary at $172,500 a year.

The Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works and the House Natural Resources Committee, along with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, are responsible for overseeing the foundation and its activities.

Congress created the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation in 1984 to augment the work of the Interior Department’s Fish and Wildlife Service and the Commerce Department’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

In the 37 years since then, the nonprofit foundation has become the nation’s largest private grant-maker for conservation initiatives, according to its website.

Trandahl and foundation staffers foster conservation partnerships with U.S. corporations, federal agencies, other nonprofits, and individuals in all 50 states. The foundation, with a 2020 budget of $355.9 million and about 145 employees, says it has supported almost 20,000 conservation initiatives.

According to its mission statement, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, known as NFWF, is “dedicated to sustaining, restoring and enhancing the nation’s fish, wildlife, plants and habitats for current and future generations.”

Echols, whose time at the foundation included a stint as acting executive director, expressed support for its overarching mission to protect wildlife habitats. But at the same time, he said, he sees problems with the execution.

“The mission has stayed the same and it’s a good mission,” Echols said, adding:

But my concern now is [that] NFWF is not as innovative as it was in looking to build new kinds of partnerships to solve broad-based conservation problems. They still do some great work, but it is much more formulaic and entrenched compared to the innovation that it had at one time. In conservation, one of the limiting factors is how much money is available. Another limiting factor is using it effectively.

What’s commonly lost is the idea that we don’t just need more money. We need more for our money. NFWF pioneered the matching grant system, but it needs to take a harder look at who is getting the money. They need to ask how much is going to groups who are innovating, like mom-and-pop institutions and not just the larger institutions.

The latest Form 990 for the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation shows top officers making more in 2018 than what CEOs of other nonprofit conservation groups typically received.

Thomas Kelsch, a senior vice president, made $622,778 and Timothy DiCintio, another senior vice president, made $632,991. Lila Helms, an executive vice president, made $572,977; Tokunbo Falayi, chief financial officer, $376,316; and Holly Bamford, chief conservation officer, $471,185.

The salaries for the foundation’s CEO and officers far outpace what is earned by top officials at the Interior Department.

Current government records show the interior secretary, a Cabinet official, makes $219,200 and the deputy secretary makes $199,300. Assistant secretaries make $172,500, according to the executive schedule setting salaries for top officials across all agencies.

Whitney Tilt, director for conservation at the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation from 1988 to 2003, told The Daily Signal that he and colleagues were subjected to tight oversight from the Interior Department, that agency’s Inspector General’s Office, and members of Congress during his time operating a grant program.

“When I was there, we received what I might call a proctologist’s exam fairly regularly,” Tilt said in a phone interview. “From GAAP [Generally Accepted Accounting Principles] and OMB [Office of Management and Budget] audits to congressional oversight, we were examined. But it was good for us and good for accountability.”

Tilt added:

We were brought before congressional committees regularly to give a full accounting of how the grant program was running and how the funds were being used. They never found anything that was inappropriate. I believe very much in the mission of NFWF.

I have no context for how it’s operating today, but must assume they are still delivering conservation success, otherwise they would not receive support from their agency, corporate, and individual sponsors. And I don’t think the board would just sit by and let salaries be paid out like this without sound and accountable reasoning. They must be doing some great conservation.

In a 2017 report, the Congressional Research Service describes the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation as a conduit for public-private partnerships:

NFWF activities are supported through gifts of property and capital and through funds arising from regulatory actions or from requirements for project mitigation or legal settlements. These contributions come from a variety of sources, both federal and nonfederal. Since its inception through FY [fiscal year] 2015, NFWF has managed a total of $3.5 billion in grants. In FY 2015, NFWF provided $87.6 million in support from various federal agencies; $0.4 million in other public funds; $38 million in private funds; and $132.4 million in directed funds, primarily related to an oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

The legislation creating the foundation, the report adds, “specifies that funds provided to NFWF from all federal agencies are to be administered by NFWF as matching grants, with the federal funds constituting no more than half of the grant and the nonfederal partner(s) providing at least half.”

When Congress initially chartered the foundation, it received financial support from the Interior Department to cover administrative costs. This support ended in 1989, prompting the foundation to move from the agency to other offices in Washington.

The director of the Fish and Wildlife Service and the undersecretary of commerce for oceans and wildlife sit on the foundation’s 30-member board as ex officio voting members. Board members serve with the approval of the interior secretary, currently Deb Haaland.

The Daily Signal asked the Interior Department’s Office of Inspector General whether it had any concerns about salaries paid to Trandahl and other officers at the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation.

The Daily Signal also asked the press office at the Fish and Wildlife Service, part of the Interior Department, whether its representative on the foundation board received reports about foundation activities and whether it had any concerns about salaries at the foundation.

The Fish and Wildlife Service had not responded at publication time, but the Interior Department’s Office of Inspector General acknowledged The Daily Signal’s phone message and invited anyone concerned about foundation salaries to submit a complaint online.

Bonner Cohen, a senior fellow with the National Center for Public Policy Research, a free market think tank in Washington, said he is skeptical that any genuine oversight has taken place during Trandahl’s 15-year tenure as CEO of the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation.

“No one should be surprised that a congressionally chartered foundation, created 37 years ago, has evolved in ways that make a mockery of its original mission,” Cohen said in an email to The Daily Signal, adding:

That’s the nature of mission creep, a chronic Washington disease. Nowhere in NFWF’s charter does it say that the foundation should serve to enrich its executive director and other high-level employees. This happened because there has been no oversight worthy of the name, either by the NFWF’s board or by Congress. Absent adult supervision, these obscene levels of compensation will continue. While millions of Americans saw their livelihoods destroyed during the pandemic-related lockdowns, life was good at the NFWF.

The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation emphasizes accountability, transparency, and efficiency on a part of its website that seeks corporate and government partners:

On average, our return on investment is three to one. NFWF’s operations are structured to be as lean as possible, with just four percent of our budget going to administrative costs. We put 96 cents of every dollar into priority actions to protect and restore fish, wildlife and their habitats across the United States and beyond. We bring a results-oriented approach, transparency, accountability and national network of contacts to each collaboration.

Nick Loris, vice president of public policy for the Conservative Coalition for Climate Solutions, said he is keen on the idea of public-private partnerships similar to what has been up and running at the foundation. But Loris also expressed concern that high salaries come with an “opportunity cost,” and said he sees a need for greater transparency.

“Injecting individual and corporate money can be an effective tool for conservation efforts,” Loris said in an email to The Daily Signal, adding:

However, policymakers should demand more accountability and transparency. Even if the law currently prohibits federal funds from flowing to NFWF, the fact of the matter is that it’s a federally chartered nonprofit. More transparency will ensure that funds aren’t flowing to the projects that have the highest political rates of return and instead to the ones that improve our environment.

And certainly individuals should be compensated for the value they create for an organization, but there is an opportunity cost, too. Dollars allocated toward exorbitant salaries cannot simultaneously be dedicated to conservation.

The Washington-based National Council of Nonprofits, which helps nonprofits advance their missions, recommends that those overseeing nonprofits—such as NFWF board members—“conduct a review of what similarly-sized peer organizations, in the same geographic location, offer their senior leaders” in salary and other compensation. The council also details what the IRS views as reasonable for nonprofit compensation.

In an email to National Fish and Wildlife Foundation spokesman Rob Blumenthal, The Daily Signal asked whether the foundation had any comment on the methodology used to determine salaries for its CEO and other officers. The Daily Signal also asked whether Trandahl continued to be paid more than a million dollars a year in 2019, 2020, and 2021.

Blumenthal emailed a response defending the foundation’s compensation practices. In it, Beth Christ Smith, vice president of human resources, said:

The foundation follows a rigorous process, including the use of outside, independent experts for compensation and market surveys to ensure reasonableness in setting executive pay. Given the unique value Mr. Trandahl’s experience and expertise brings to NFWF, we are confident his compensation, as well as the compensation of other senior leaders at the foundation, has been appropriately set by the Board of Directors.

Katie Tubb, an energy policy analyst with The Heritage Foundation, said she is not optimistic about the prospects for any serious oversight by the Interior Department. (The Daily Signal is Heritage’s multimedia news organization.)

Tubb, however, does see an opportunity for Congress to evaluate the foundation’s practices.

“I’m skeptical that Interior would have the incentive to do oversight, because the foundation can be used as a tool for the Biden administration to accomplish a lot of its goals without oversight,” Tubb said.

“The Biden administration has this huge appetite to acquire new federal lands and extend federal control over private lands, and an organization like the foundation could be viewed as a handy tool to help them do this,” she said.

Tubb also points to “yellow flags” in the Congressional Research Service report in 2017 that raise questions about how the foundation has used private funding sources. House and Senate members might pursue lines of inquiry there, she said.

The Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010, and the subsequent criminal settlement agreements between London-based BP and the Obama Justice Department, figures prominently in this equation.

The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation was set to receive more than $2.54 billion for Gulf Coast restoration from 2013 to 2017, according to the Congressional Research Service report.

The foundation goes into detail about what it received from the legal settlement after the BP oil spill and how the funds were used to “fund projects benefiting the natural resources of the Gulf Coast that were impacted by the spill.”

The foundation created the Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund, which it says has supported 183 projects worth about $185 billion.

“Did the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation fulfill its commission after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill to spend this money appropriately?” Tubb asks. “This sounds like a great place for Congress to step in and figure out what happened here.”

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email letters@DailySignal.com and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the URL or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state