Now 15 months after Congress first responded to the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s evident that unprecedented federal unemployment insurance bonus benefits are hurting the recovery, making it harder for businesses to find the workers they need to recover, and harder for consumers to find the products and services they want at prices they can afford.

Moreover, prolonged unemployment benefits contribute to a smaller economy, higher deficits, and most importantly, poorer outcomes for the long-term unemployed.

President Joe Biden claimed that generous unemployment compensation has not had a “measurable” effect on the poor jobs recovery and worker shortages.

The Daily Signal depends on the support of readers like you. Donate now

And in response to 25 governors announcing they would end the $300/week federal unemployment bonuses early so that employers in their state no longer have to compete with the federal government, Biden is trying to find a way to keep the federal unemployment bonuses coming—despite those governors’ attempts to aid their states’ recoveries.

>>> WATCH: Paying Americans not to work hurts society’s most vulnerable people. Hear from Patrick Driscoll, a severely disabled man in need of care, who was left without caregivers in the wake of poorly planned stimulus spending. Watch the mini-documentary here.

Here are nine indications that it’s time for the federal government to get out of the way of the recovery:

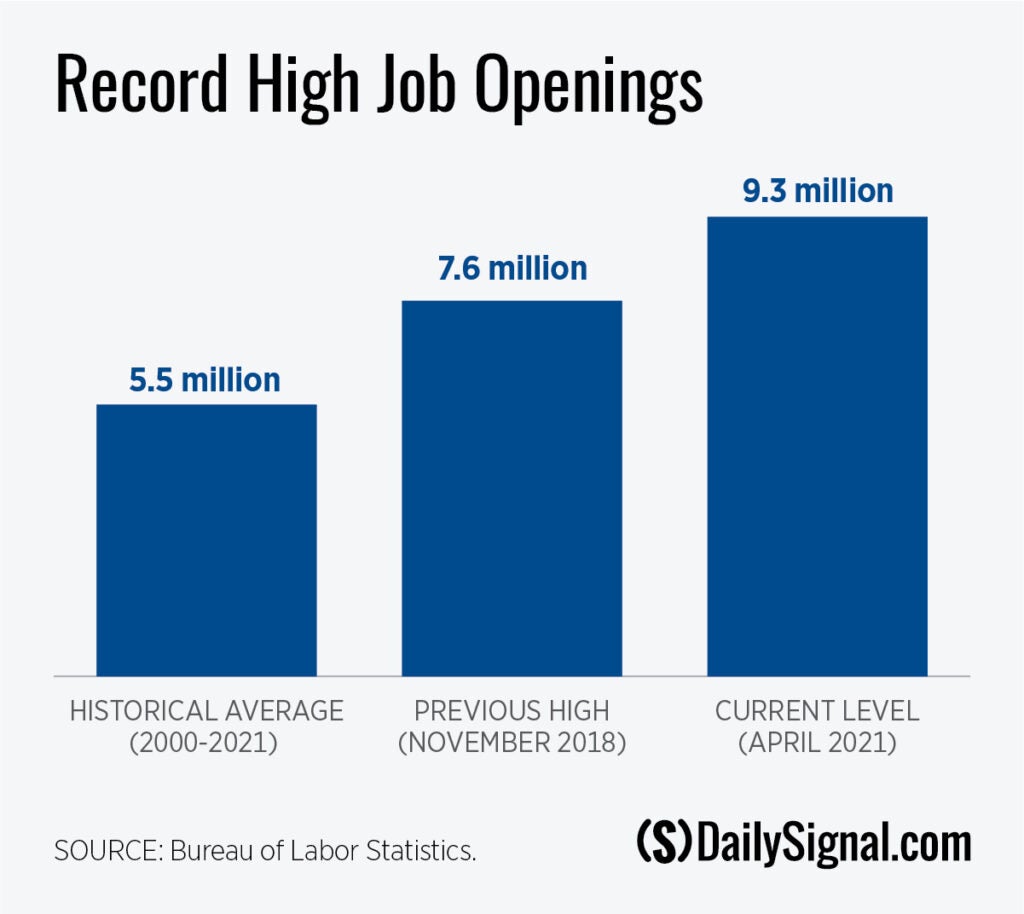

1) Record-high 9.3 million job openings: April marked the second straight month of record-high job openings, with 9.3 million jobs available. Prior to April, the next-highest number of job openings was 7.6 million in November 2018, and the historical average (since the data began in 2000) is 5.5 million.

2) Record-high job openings rate: The job openings rate—which accounts for a growing economy by measuring job openings as a percent of all filled and unfilled jobs—also hit a record high 6% in April. Prior to the past three months, the job openings rate had never exceeded 4.7%.

3) One job opening for every unemployed worker: The latest data shows 9.3 million job openings and 9.3 million unemployed workers. Unemployed workers are defined as wanting a job and actively looking for one, and in order to receive unemployment benefits, applicants must say that they are looking for work. The last time the unemployment rate was at a similar level of 5.8% in 2014, there were half as many jobs available—4.7 million vs. the current 9.3 million. While geographic variation such as Hawaii’s tourism-dependent economy and skills mismatch mean that all the job openings don’t completely align with unemployed workers, a lack of available jobs cannot explain excessive unemployment.

4) Record-high “quits”: As 4 million workers quit their jobs in April (2.7% of all employees), the number and rate of “quits” also hit record highs. The more options that workers have available to them—including the ease with which they can find another job and the availability and generosity of unemployment insurance benefits—the more likely they are to quit. Policymakers in favor of ongoing unemployment bonuses argue that some workers are quitting their jobs out of fear of catching COVID-19. But rising quits alongside widely available and increasing vaccinations doesn’t make sense.

5) Record-low layoffs: The final record-setting statistic for April was a record-low number (1.444 million) and rate (1%) of layoffs and firings. Employers report a strong hesitancy to lay workers off, even if they violate workplace rules or refuse to perform certain jobs, because it’s so hard to find replacements.

6) Unemployment claims exceed unemployed workers: There are 15.9 million people filing unemployment insurance claims, but only 9.3 million unemployed workers. There should never be more workers receiving unemployment insurance benefits than there are unemployed workers. Increased eligibility for unemployment benefits—extending them to workers who do not pay into the unemployment system and eliminating or loosening many verification processes—has contributed to an unprecedented number of unemployment benefit claims and payouts. All told, the pandemic-related unemployment insurance expansions will likely cost taxpayers more than $100 billion in improper payments.

7) Companies are competing for workers: The president might not consider it “measurable,” but across the country, Americans have seen the “We’re hiring” signs or the “We’re sorry for the wait; we’re short-staffed” apologies. And then there are all the pay and benefits increases. Cedar Point Amusement Park in Sandusky, Ohio, for example, doubled its starting wages to $20 per hour and still will only have enough workers to open on a limited schedule. Amazon is offering $1,000 signing bonuses, even to those with no experience, and companies such as Chipotle and Taco Bell are providing college tuition assistance and paid family leave benefits—all in an effort to attract workers. These added pay and benefits are nice for the workers who receive them, but they also translate into higher prices for consumers, and ultimately less purchasing power even for the employees who receive higher wages.

8) People respond to incentives: Studies consistently show expanded unemployment benefits lead to expanded unemployment. Researchers at the New York Federal Reserve estimated that extended unemployment benefits during the Great Recession (up to 99 weeks) led to the number of unemployed workers being between 3.3 million and 4.6 million higher in 2010 and 2011 than it would have been without the extended benefits. And evidence from increased benefit levels suggests that a $300 per week bonus would extend people’s unemployment durations by an extra six to 14 weeks.

9) Child care struggles are not hurting parents’ employment: Initially, child care and school closures associated with the COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately affected parents’—particularly mothers’—employment. But it’s no longer the case that women have been disproportionately affected, and a study by former President Barack Obama’s former chairman of his Council of Economic Advisers found that employment among parents of young children has declined by less than workers without young children and that child care issues that have pushed young women out of the workforce account for “zero” of the pandemic-related reduction in employment.

It’s time for the federal government to stop stimulating demand and restricting supply by pumping more deficit-financed spending into the economy and by proposing trillions of dollars in new government programs.

Employers already face high costs from government taxes and regulations. They don’t also need the government competing with them. Policymakers should end the federal unemployment insurance bonus payments now.

And instead of bankrupting young workers and children by taking out ever-increasing debt in their names, policymakers should commit to a fiscally responsible post-pandemic budget that will help prevent a financial crisis by putting America on track toward fiscal sustainability.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email letters@DailySignal.com and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the url or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.