At first glance, Nebraska’s K-12 education system seems to be doing fairly well. On the fourth- and eighth-grade math and reading components of the 2019 National Assessment of Educational Progress, Nebraska students scored slightly above average overall.

But a closer look shows a more worrisome picture.

The Urban Institute reanalyzed the NAEP data while controlling for students’ age, race or ethnicity; special education status; free and reduced-price lunch eligibility; and their status as English language learners.

The institute found that Nebraska students’ adjusted scores on each of the tests were significantly lower. The state’s adjusted overall scores are middling at best, and some are below average.

Even worse, Nebraska’s achievement gap is wider than the national average and growing.

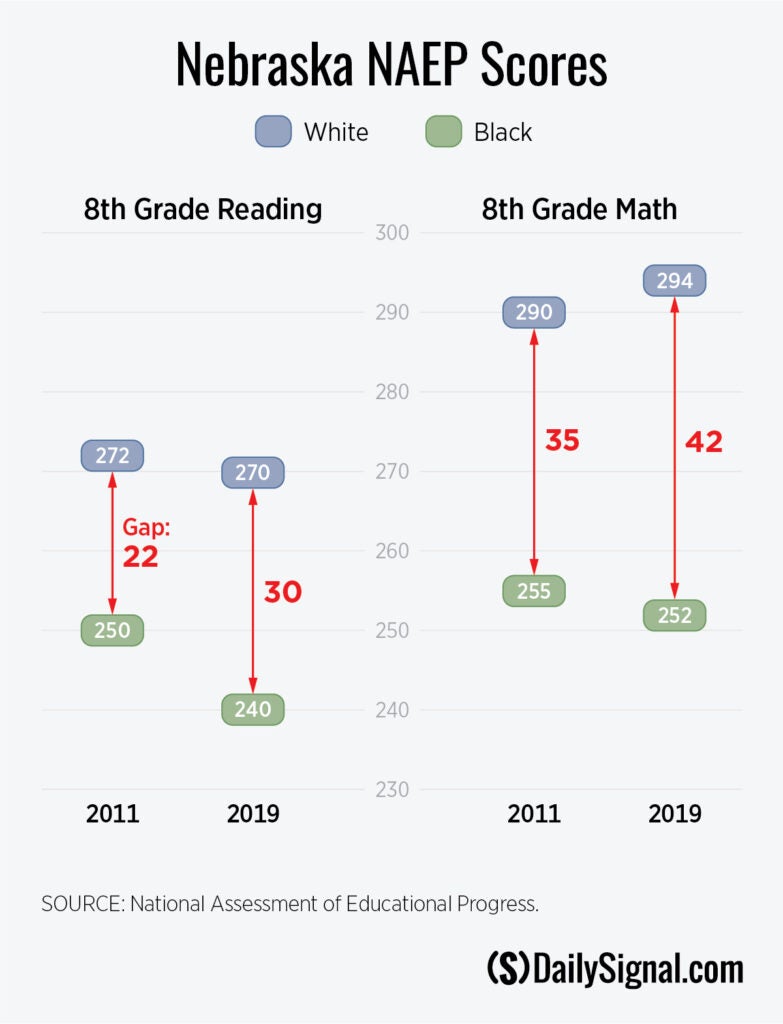

In 2011, the black-white achievement gap was 22 points on the eighth-grade NAEP reading test and 35 points on the eighth-grade NAEP math test. Ten points on the National Assessment of Educational Progress is the equivalent of about a year of learning, so a decade ago black eighth graders in Nebraska were about two to three-and-a-half years behind their white counterparts.

On the most recent NAEP, the black-white achievement gap had grown to 30 points on the eighth-grade reading test and 42 points on the eighth-grade math test. In other words, Nebraska’s black students now are behind white peers by about three to four-plus years of learning.

Last week, Nebraska state policymakers from both sides of the aisle pleaded with their colleagues to do more to close the achievement gap.

That gap is widening despite extensive, expensive efforts to close it. Over the past two decades, untold initiatives by state government bureaucrats, school district officials, and related associations and private philanthropies have attempted to close Nebraska’s achievement gap, but to no avail.

It is time to try something different. Nebraska policymakers should start by empowering families with more education options.

According to a recent study by the University of Arkansas, states with more robust education choice policies—such as school vouchers, tax credit scholarships, K-12 education savings accounts, and charter schools—tend to see achievement gains over time on the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

After controlling for factors such as per-pupil education spending, student-teacher ratios, teacher quality, household income, and more, the study found that “expanding parental options in education, in all its forms, is consistent with improvements in average student performance for U.S. states.”

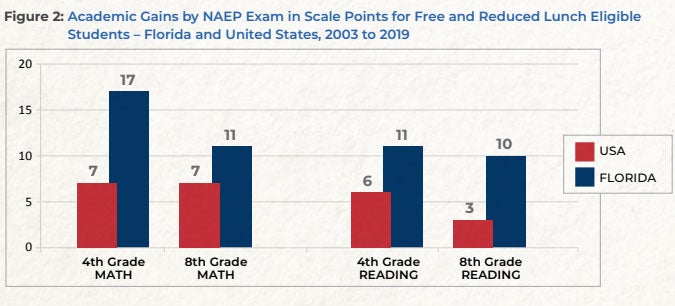

One of the states with the most robust environments for education choice is Florida. According to the University of Arkansas study, students in Florida not only have been significantly outpacing the national average in achievement gains, but the gains are even higher among the most disadvantaged students:

While the NAEP scores of low-income 4th- and 8th-graders averaged gains of three to seven points across the U.S. during those 16 years, scores for low-income students in Florida surged 10-17 points. Florida students who did not qualify for a free or [reduced-price] lunch made academic gains, but they were smaller and much closer to the national average for such students.

Source: “Education Freedom and Student Achievement: Is More School Choice Associated With Higher State-Level Performance on the NAEP?” University of Arkansas Department of Education Reform

The study also highlighted the experience of Arizona, which received the top score on the Educational Freedom Index. The study noted that from 2009 to 2015, “Arizona students were the only state group to show statistically significant gains in all six NAEP exams” (fourth- and eighth-grade math, reading, and science).

As one of the study’s authors explained in Newsweek:

Stanford University’s Opportunity Project recently published nationwide data showing that Arizona students had the highest level of academic growth from 2007 to 2018. Arizona students and educators also achieved the highest rate of academic growth both for all students and for low-income children.

In other words, education choice is the rising tide that lifts all boats. Expanding choice and competition encourages traditional public schools to step up their performance. And those who have the most to gain are those disadvantaged students who were the most choice-deprived under the status quo that assigns students to public schools based on where they live.

State policymakers who want to see students improve their academic performance increasingly seek to expand their education options.

So far this year, nine states have passed four new choice policies and expanded 10 existing ones. Nearly a dozen other states are considering similar legislation. Three states—Indiana, Kentucky, and West Virginia—adopted new policies creating K-12 education savings accounts; Florida significantly expanded its ESA program.

At the forefront is West Virginia, which had limited options until this year when it passed the most expansive education choice policy in the nation: a state-funded K-12 education savings account for all children switching out of a public school or entering kindergarten.

Cornhusker policymakers can do much more to establish policies that have been shown to close the achievement gap. At the forefront of these is expanding education opportunity for all Nebraska students, especially the most disadvantaged.

With more and more states across the country doing just that this year, there’s no reason to put off education freedom for families any longer.

This commentary was updated within eight hours of publication.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email [email protected] and we’ll consider publishing your remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the url or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.