Immediately after his inauguration, President Joe Biden issued an executive order reviving the social cost of carbon and the interagency working group tasked with making the social cost of carbon estimates.

One of the primary policy tools for imposing climate regulations on the energy sector, the social cost of carbon supposedly measures the cost of the accumulated damage for centuries to come from emitting a ton of carbon dioxide today.

Translating those projected damages into a policy-relevant number requires a financial calculation called discounting. Armed with a peculiar notion of fairness, the working group claims fairness requires biasing the discounting process, which will perversely result in greater costs imposed on poor people that will provide more benefits to rich people. It is called “intergenerational equity.”

The Daily Signal depends on the support of readers like you. Donate now

Because the global community is faced with constraints on what it can spend and invest, the sensible approach is to spend and invest on those things that have the most impact and give the greatest return.

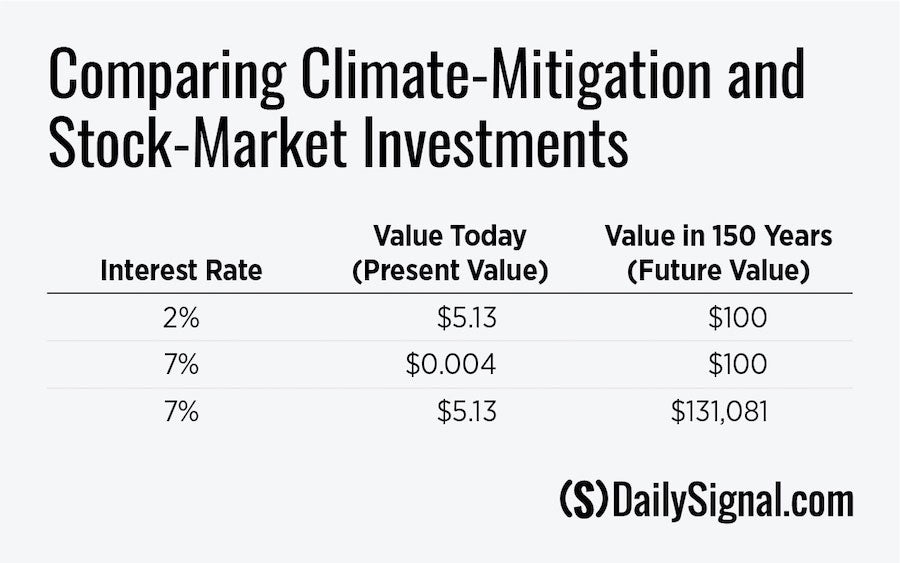

Suppose we have two investment choices, one with a real (adjusted for inflation) return of 2% per year and the other with a real return of 7% per year. It should be a non-brainer to invest in projects with the 7% return instead of those with a 2% return.

This difference is especially dramatic when investing on the timescales used for climate policies.

If the investment horizon is 150 years, then $5.13 invested today, at 2% per year, will compound to $100 at the end of the 150 years. If there was another investment that returned 7% per year, then we would only need to invest $0.004 today to get the same $100 150 years from now.

The working group looks at carbon dioxide cuts as an investment opportunity. It projects that spending money to cut carbon dioxide emissions today will produce future benefits in the form of reduced damage from global warming. The benefit from reduced climate damage is the future value expected for cutting carbon dioxide emissions today.

Though so much of the future climate damage is from model projections of increasing extreme weather, it is worth noting that there has been no significant increasing trend in hurricanes, floods, droughts, tornadoes, or wildfires for at least the past century, and the sea level has been rising only a few millimeters per year for even longer.

Nevertheless, there are a host of ways in which carbon dioxide emissions can be reduced. For example, we can turn the heat down in our buildings, we can travel less, we can add more insulation to our homes, we can drive more fuel-efficient vehicles, or we can produce energy in ways that have lower carbon dioxide emissions. All of these options involve different costs and reduce carbon dioxide emissions by different amounts.

Again, because of resource constraints, we cannot do everything that reduces carbon dioxide emissions. Therefore, the working group’s goal is to come up with a guide for helping choose which carbon dioxide cuts make sense. The social cost of carbon provides one such guide by comparing the payout from climate mitigation to the best reasonably expected payout from other investments.

If a ton of carbon dioxide emissions today could be expected to do $100 of damage in the year 2171 (150 years from now), and if the best alternative rate of return is 2% per year, the social cost of carbon would be $5.13. Any cut in today’s carbon dioxide emissions that costs less than $5.13 per ton should be made, while all cuts that cost more than $5.13 per ton should not be made.

In the jargon of economics and finance, the $5.13 is the present value of $100 received in 150 years, discounted at 2% per year. The interest rate is called the “discount rate.”

However, if the best reasonably expected alternative investments return 7% per year, the social cost of carbon drops dramatically to $0.004 per ton, with an equally dramatic drop in the level of carbon dioxide cuts that make sense. Over the past two centuries, the real gross return on investment in the New York Stock Exchange was between 7% and 100% per year. A study of the real return to the Standard and Poor’s index from 1928 to 2014 gives a similar result.

It makes no sense to invest $5.13 at 2% when the same future benefit could be had for less than a penny ($0.004) when invested at 7%. Nevertheless, that is exactly what some suggest.

They claim the higher discount rate unfairly penalizes those who will be alive in 2171 because it argues for less carbon dioxide mitigation today. However, the lower social cost of carbon when discounted at 7% does not say invest less, it says do not make that investment in carbon dioxide cuts that cost more than $0.004 per ton.

Perhaps the most dramatic way to illustrate this is to look at what is being denied those alive in 2171 if the social cost of carbon (in this simple example) were set at $5.13.

Carbon dioxide cuts that cost $5.13 per ton will only provide a benefit (in the form of reduced climate damage) of $100 in 2171. If that $5.13 were invested elsewhere at 7%, those alive in 2171 could, instead, receive $131,081 in value. It is hard to see how giving the future a thousand times as much is less fair to them than giving them one-thousandth as much.

Further, people 150 years from now are likely to be unimaginably richer and endowed with equally unimaginable technology with which they can adapt to and mitigate all sorts of adversities.

Looking back 150 years to around 1870 we see that the average income in the United States was barely a 20th of today’s average income (again, even after adjusting for inflation). This phenomenal growth in the past fits in the range of projected future growth.

Even this dramatic change does not capture all the improvements of economic and technological growth. For instance, the heart-wrenching tragedy of childhood mortality dropped 98% from 1870, when nearly a third of children did not live to age 5, to today, where the rate is less than 1%. As late as 1920, no more than 1% of households even had indoor plumbing or electricity.

The increase in the standard of living over the next three centuries should be at least as fantastic. Couching a greater trade-off of current sacrifice for future wealth as improving intergenerational equity gets the concept exactly backward—it is taking from the poor generation to give to the rich generation.

For simplicity, the example for the social cost of carbon used here has a hypothetical climate damage for only the year 2171. The working group will use models that capture varying amounts of climate damage for centuries into the future, but the basic principle still holds: unreasonably low discount rates will still have orders of magnitude impacts on increasing the value of the social cost of carbon.

The proponents of lower discount rates seek to force the current, poorer population to spend more to cut carbon dioxide (primarily through higher energy costs) under the guise of intergenerational equity.

Estimating the social cost of carbon is susceptible to political pressure and model-gaming. The assumptions in play—about unsupportable time horizons, exaggerated emissions projections, overly high estimates of carbon dioxide’s impact on warming, and others—are all too easily corrupted, resulting in wildly varying estimations.

In fact, reasonable assumptions can push the social cost of carbon negative (which implies that a policy of subsidies for carbon dioxide emissions is the answer). However, the single input that has the most potential to overstate the social cost of carbon is understating the discount rate. The constant pressure to justify ever lower discount rates for social cost of carbon calculations is almost comical when it mistakes wealth for poverty.

Indeed, it is a strange notion of equity that says policies should take larger amounts from a group of poorer people (those alive today) to provide benefits for a richer group (those alive 100, 200, or 300 years from now) and to do so with abominable inefficiency.

The Daily Signal publishes a variety of perspectives. Nothing written here is to be construed as representing the views of The Heritage Foundation.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email letters@DailySignal.com and we will consider publishing your remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature.