Critical race theory is in the news these days, but many people still may not know what it really means. They think critical race theory is part of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s civil rights efforts. In truth, it is directly opposed to the central concept and vision he most stood for.

One of the last and greatest civil rights leaders of our time—and one of King’s closest friends and advisers—did understand critical race theory, and explicitly rejected it.

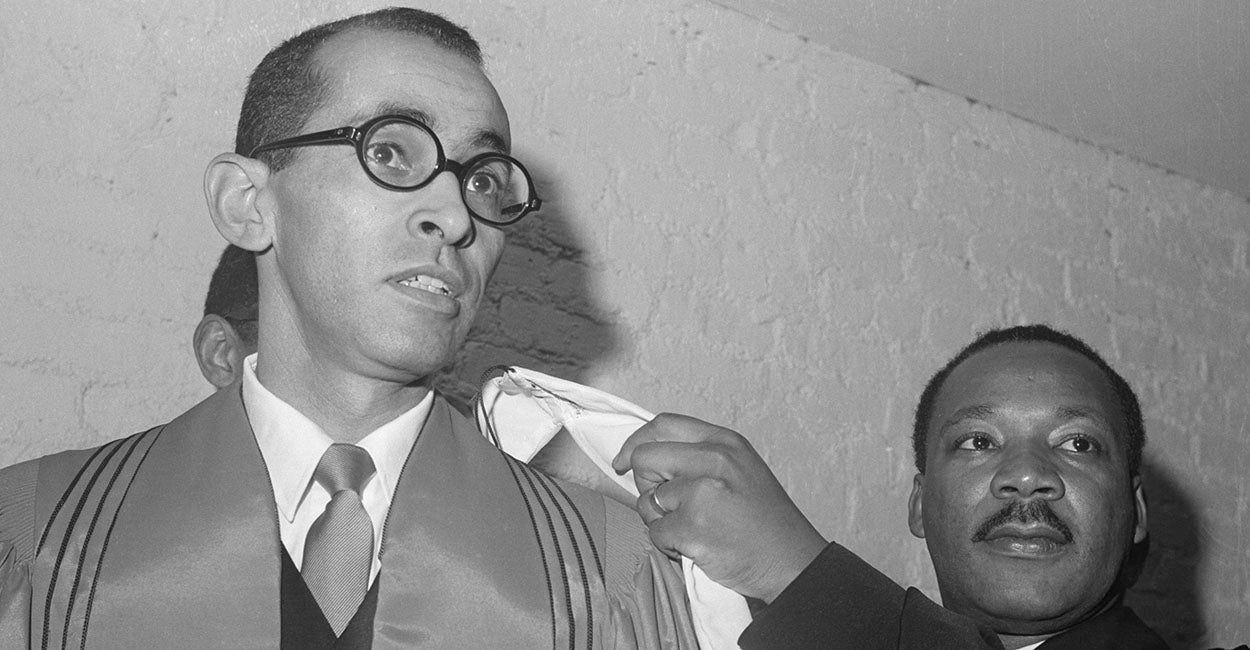

Wyatt Tee Walker was a legend in the American civil rights movement. Executive director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in the critical years of 1960-1964, he was a co-founder of the Congress of Racial Equality, chief of staff to King, and King’s “field general” in the organized resistance against notorious Birmingham safety commissioner “Bull” Connor.

The Daily Signal depends on the support of readers like you. Donate now

Walker compiled and named King’s “The Letter From Birmingham Jail.” He was with King for the March on Washington that produced the “I Have a Dream” speech, and in Oslo for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Afterward, Walker came north to New York City to serve as minister of the Canaan Baptist Church of Christ in Harlem. He was one of the nation’s most respected ministers until his death in 2018. In his book “David and Goliath,” Malcolm Gladwell dedicated a chapter to Walker and his work in Birmingham. The cover of Ebony magazine called Walker “The Man Behind Martin Luther King.”

In short, no one may have known King’s thoughts better or been closer to them than Walker.

Even as he aged, Walker never backed down from the passionate pursuit of civil rights for all. Later in his life, he was chairman of the Rev. Al Sharpton’s National Action Network and a supporter of reparations for African Americans.

I got to know him soon after Amadou Diallo had been horribly gunned down in New York City in 1999. We joined together to form New York’s first and longest-surviving charter school, now named the Sisulu-Walker Charter School of Harlem. We stayed friends from that time until he died.

In 2015, Walker and I co-authored an essay about education reform and race relations, where we wrote:

Today, too many ‘remedies’—such as Critical Race Theory, the increasingly fashionable post-Marxist/postmodernist approach that analyzes society as institutional group power structures rather than on a spiritual or one-to-one human level—are taking us in the wrong direction: separating even elementary school children into explicit racial groups, and emphasizing differences instead of similarities.

The answer is to go deeper than race, deeper than wealth, deeper than ethnic identity, deeper than gender. To teach ourselves to comprehend each person, not as a symbol of a group, but as a unique and special individual within a common context of shared humanity. To go to that fundamental place where we are all simply mortal creatures, seeking to create order, beauty, family, and connection to the world that—on its own—seems to bend too often towards randomness and entropy.

Before publishing this essay, I questioned Walker to make sure he really wanted to be on record with this opposition to critical race theory. I was worried this might put him in a bad way with other civil rights leaders. But he had never backed down in his life, and he reiterated that this was his position.

In hindsight, I believe that Walker was not so much against anything, as for something. He was for what King was for, and for what so many well-intended people are for who may misunderstand the difference between critical race theory and traditional (i.e., King-style) civil rights.

Walker was for a fundamental respect for all people, without regard to their ethnic group or religion or the color of their skin. Walker’s civil rights views tie back to religious values, to humanism, to rationalism, to the Enlightenment.

The roots of critical race theory are planted in entirely different intellectual soil. It begins with “blocs” (with each person assigned to an identity or economic bloc, as in Marxism). Human-to-human interactions are replaced with bloc-to-bloc interactions.

As Walker tried to make clear, thinking in terms of blocs of people, rather than of people as individuals, leads to a whole set of insidious results.

How can two people bind together in friendship if they are members of power blocs that are presumed to be inherently opposed?

How can a person prove his innocence if he is branded as inevitably a part of a guilty group?

Why should an individual strive to succeed by individual merit if group dynamics are presumed to be overwhelming and inescapable?

How can we ever find peace among the races and religions if we won’t look to each other, person by person, based on actual facts and actual intentions?

The saddest thing is to see well-intentioned people, trying to achieve Martin Luther King’s dream by employing critical race theory methods, that are the opposite of King’s dream. King asked for everyone to be judged by the content of their own individual character, not by their inescapable genetic links to post-Marxist-style analytical power groups.

Supporters of civil rights should follow the example of Walker, and not allow the two incompatible definitions of civil rights—King’s and critical race theory—to be confused with one another.

Originally published by RealClearPolitics