Bipartisanship might be rare in the halls of Congress, but the U.S.-Colombia relationship defies that stereotype. For decades, policymakers on both sides of the aisle have understood the importance of sustained U.S. commitment to Colombia’s peace, stability, and security.

While legislators often lose sight of the long view required in foreign policy, congressional oversight and leadership helped transform Colombia from the brink of being a failed state to a regional leader in a few short decades.

In turn, the U.S.-Colombia strategic relationship has become a key pillar of Latin America’s stability, U.S. regional interests, and a success story of U.S. strategic engagement.

The Daily Signal depends on the support of readers like you. Donate now

However, recent, ideologically-driven provisions adopted in the House’s National Defense Authorization Act would undercut the longstanding bipartisanship of Colombia policy. If enacted, they would weaken Colombia’s ability to protect itself from criminal organizations and worsen its booming cocaine production.

One provision in the House, put forward by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., seeks to eliminate U.S. funding for aerial eradication of coca crops—the raw ingredient in cocaine.

Consider the following facts to understand how unwise and irresponsible this policy would be.

In 2015, Colombia terminated its U.S.-funded aerial coca eradication program, leading to a massive increase in coca cultivation and cocaine production numbers. Between 2014 and 2018, there was a historic spike in coca crop cultivation rates, and with it, an accompanying increase in potential cocaine production.

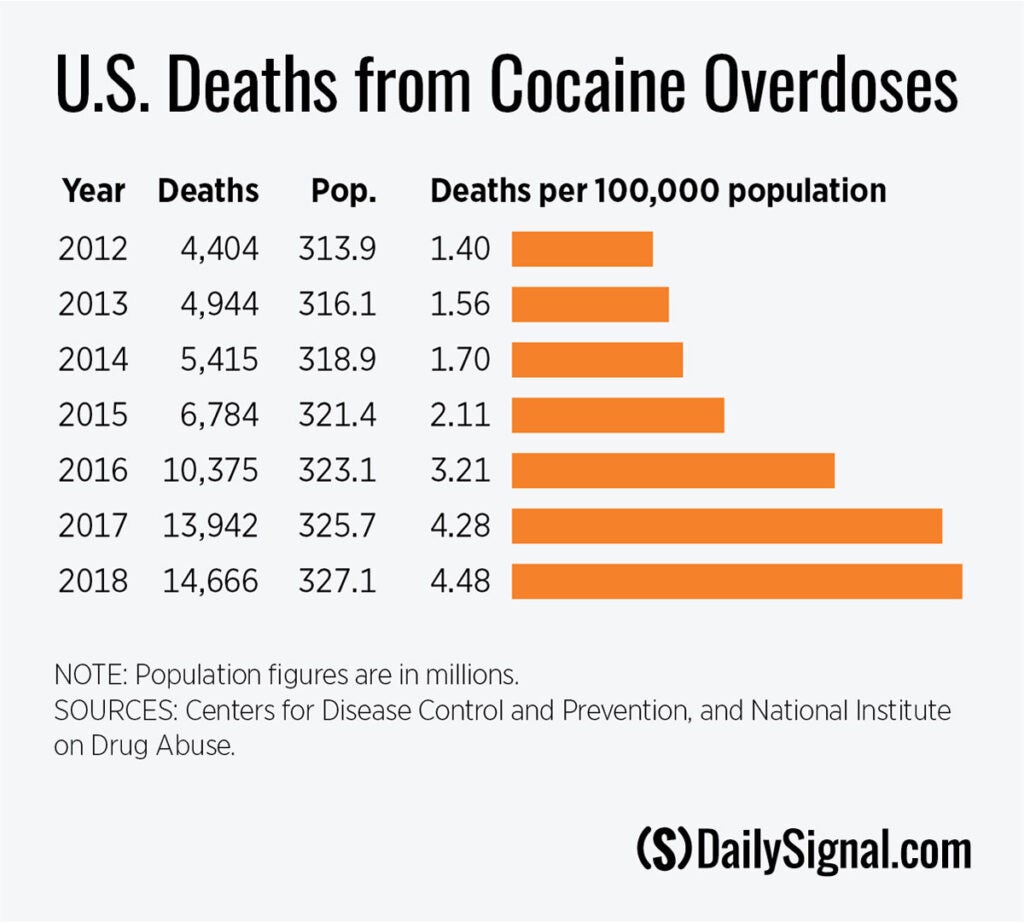

In 2014, 112,000 hectares (roughly 277,000 acres) of coca were cultivated, in comparison to 208,000 in 2018. During this time, U.S. cocaine overdoses also increased.

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration estimates that 90% of the cocaine seized in the U.S. is of Colombian origin.

When Colombia terminated its aerial coca spraying program, it cited a World Health Organization report that has since been disproven (by the World Health Organization itself).

The initial report claimed the herbicide glysophate was “possibly carcinogenic to humans.” Within a year, a later report stated that glysophate’s ability to cause cancer was “unlikely,” thus disproving the health basis for the original decision.

At this point, the damage was done. Despite the objections of Colombia’s minister of defense at the time and other security officials, the program was terminated.

Since then, Colombia has largely relied on manual eradication to get rid of coca crops. Soldiers have been forced to manually eradicate in areas controlled by criminals and a terrorist group. They often encounter armed criminals, land mines, and sniper shootings.

According to Colombia’s president, manual eradication is far less efficient or cost effective. They can only eradicate 2 to 3 hectares per day, whereas aerial spraying destroys 120 to 150 hectares and costs more than two times less.

Barring any additional judicial setbacks, Colombia is set to resume its aerial spraying program with U.S. support this fall. The U.S. should not handicap Colombia’s efforts to contain its spiraling cocaine production problems.

Nor should U.S. policymakers hamper Colombia’s peace and reconciliation process with ideologically-driven policies.

An amendment by Rep. Jim McGovern, D-Mass., would require the U.S. departments of Defense and State, as well as the director of national intelligence, to deliver a report in four months on 16 years of U.S. intelligence and defense activities in Colombia.

In his own words, McGovern’s intentions are not oversight, but rather a backdoor to his ultimate goal of suspending U.S. assistance to Colombia. McGovern recently said, “If it was up to me, I would end security assistance to Colombia right now.”

Recent revelations of illegal spying against members of Colombia’s civil society have renewed calls for stricter oversight of Colombia, and for the country to be held to stricter human rights standards. On that point, we should all agree. Illegal spying has no place in a democratic country and guilty officials should be punished.

Cutting off U.S. support will not improve the human rights situation and in fact, the lack of oversight and engagement will worsen the situation. Depriving Colombia of U.S. resources will reduce its ability to implement its ambitious peace agreement and reconciliation after over 50 years of conflict. It will also be left with less means to take care of the more than 2 million Venezuelan refugees and migrants inside of Colombia.

The relationship and the situation in Colombia is not without its challenges. Despite significant U.S. and Colombian investments, cocaine production remains an elusive challenge. The U.S. must get its demand issue in order. Inadequate implementation of the peace plan has left victims of Colombia’s conflict without justice and meaningful participation in Colombian society. Small numbers within its security forces guilty of human rights violations have still not been held liable for their crimes.

Yet Colombia’s transformation from a country where kidnappings and capital city bombings were a common occurrence only decades ago to a regional security leader and economic powerhouse should be commended.

Congressional bipartisanship allowed for sustained U.S. commitment and paved the way for these achievements. The National Defense Authorization Act conference should not allow for the agendas of fringe ideologues to undo decades of hard-fought gains.