Over the past 10 to 15 years, the United States has added a new tool to its foreign policy: targeted individual sanctions. Although it has made good use of broader sanctions—Iran and North Korea come to mind—the U.S. is increasingly taking action against specific violators.

Given the complexity of U.S.-China relations, targeted sanctions are a particularly good instrument for U.S. foreign policy toward China.

That is why the Trump administration has so often resorted to them, most recently to penalize Chinese officials responsible for human rights violations against the Uighur Muslim ethnic minority and for Beijing’s ongoing attack on Hong Kong’s autonomy.

The Daily Signal depends on the support of readers like you. Donate now

The administration should be commended for this. But sanctions reportedly under consideration against all members of the Chinese Communist Party and their families would take U.S. policy backward.

The proposed sanctions may not be as draconian as banning investment or prohibiting Chinese imports. The idea is to impose only a visa ban. But the Chinese Communist Party has 92 million members. It’s bigger than most countries in the world. Include their families, and you’re talking about prohibiting a quarter of China’s population from visiting the U.S.

The broader debate over how the U.S. should understand the influence of the Chinese Communist Party contains two extremes.

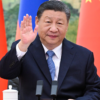

The first—which is much less prevalent than it once was—is that belonging to the Chinese Communist Party is like being a Rotarian or member of Toastmasters. It’s far more than that. Marxist-Leninism, Maoism, and what party cadres now call “Xi Jinping Thought” are part of a fully developed political ideology with real-world, often horrific consequences.

Party members are trained in these ways of thinking. By the time he reaches the Politburo or other positions of national responsibility, a Chinese leader is thoroughly versed in what it means to be a communist.

The other extreme—reflected in the reported visa ban—is that the party is a monolith marching to the greater glory of communist China. In fact, the vast majority of party members are driven by professional ambition and the desire to provide a leg up for their families.

Now, if the intention of the travel ban for party members is to encourage otherwise good people to forgo party membership and a better life where they are, in exchange for a visit to the U.S. (which may be beyond their means in any regard), it is nothing short of delusional.

Xi and the party’s standing committee—maybe the entire Politburo—might be committed communists. The Chinese people themselves, on the other hand, are generally pragmatists. The further you go down in the ranks of the party, the more this is true.

Sometimes, even dissidents come from within the party. They shouldn’t be lumped together with the perpetrators of the crimes against the Uighurs. Critics such as Dr. Li Wenliang, the late doctor who tried to warn the world about the severity of COVID-19, was a party member.

Ultimately, systemic change in China will come from within the Chinese Communist Party.

Think of the most hopeful period in China’s political development, the late 1980s. The “good guys” in leadership were no Jeffersonians. They were Communist Party general secretaries Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang. Yet, it was they who sought to provide Chinese citizens greater political space and defend student protesters.

In the end, Deng Xiaoping accommodated the villains of that story. He sided with hardliners in crushing the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989. But Deng is also responsible for ushering in China’s era of economic liberalization. Deng, of course, was a consummate and loyal member of the Chinese Communist Party.

The best way forward is to continue to single out those party members who do threaten our interests and the universal values we share with the Chinese people, no less than any other.