Is America headed for a French-style revolution along the lines of the one in 1789?

Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., said as much in a tweet comparing Democrats to French revolutionaries.

The Daily Signal depends on the support of readers like you. Donate now

But some of the responses to him were strange, to say the least.

Dan Saltzstein, an editor at The New York Times, responded in a now-deleted tweet:

“The French Revolution, you say? In which rising social and economic inequality led to a democratic overthrow of a monarchy and the establishment of a republic? That French Revolution?”

Katelyn Burns, a writer for Vox, in a tweet that also has since been deleted, wrote: “Ah yes, the French Revolution, which threw an out of touch royalty and aristocracy out of power to install an American-style democracy. Truly an evil forebear for … *checks notes* American democracy.”

The French Revolution was not a forebear of American government, which should be clear to any sober student of history.

The French Revolution—as opposed to the American Revolution—turned from the limited goal of ending arbitrary government to a maximalist goal of overturning all society and culture in the name of liberte, egalite, fraternite—liberty, equality, and fraternity.

It ended with none of those things—just years of violence and the birth of a more absolute tyranny.

Unfortunately, it looks like odes to the French Revolution are not exclusive to Twitter. Some protesters have picked up on the idea that they will bring a French-style revolution to the U.S.

In Seattle’s Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone—since renamed the Capitol Hill Organized Protest, or CHOP—protesters chanted a few weeks earlier:

“Does anybody know what happened to the people who did not get on board with the French Revolution?”

“Chopped” was the answer, an oblique reference to the guillotine.

That’s true. But what happened to those who were on board with the revolution? They got chopped, too.

Certainly, the French people had innumerable reasons for discontent with the Ancien Regime, the French monarchy, which had become deeply corrupt and obnoxious in its rule.

Many great minds of the era, among them Thomas Jefferson, who had been an ambassador to France, bought into the idea that the French Revolution would simply be a continuation of what had happened in America just a few short years earlier, and that it was a necessary counter to a dysfunctional and abusive system that existed in France.

“[Jefferson’s] years in France showed the palpable moral decay of the Roman Catholic Church hierarchy, the autocratic and dysfunctional structure of the Bourbon monarchy, and the diffident disinterest in duty of the aristocracy,” historian Miles Smith IV wrote for The Washington Examiner. “This understandably convinced Jefferson that the French people endured a government entirely unresponsive to the basic functions and needs of society.”

On that, Jefferson was correct.

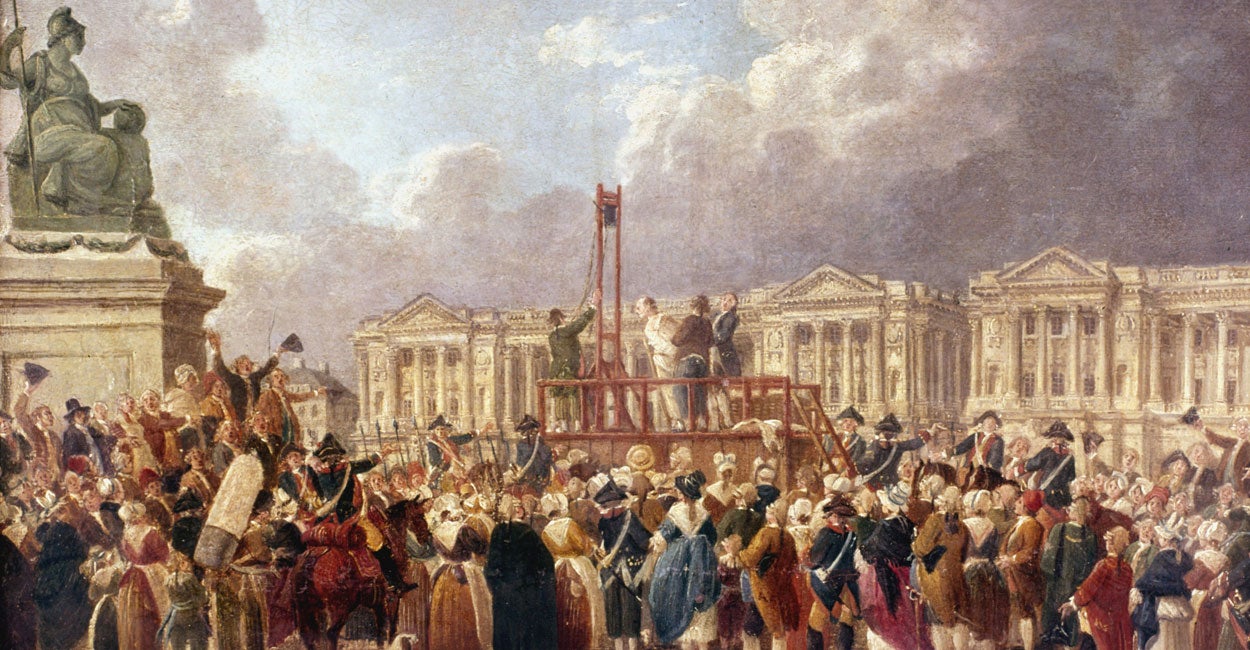

But very soon after the famed storming of the Bastille in 1789, the French Revolution turned to wanton violence, destruction, and mass killings, eventually consuming nearly all of its leading adherents.

As revolutionaries concluded that their maximalist aims at leveling society could not be achieved through the slow process of deliberation, compromise, and genuine tolerance, they began destroying art, statues, and property—both public and private—in the iconoclastic desire to repudiate the social mores of their country’s past.

The radicals did this as they turned to outright killing of their enemies of the present. Mass purges of art and symbols of religion turned to mass executions of the enemies of the revolution.

Tens of thousands were killed and executed throughout France as the revolution consumed itself.

Even Maximilien Robespierre, dubbed “the incorruptible,” who led the Reign of Terror, saw its conclusion when he and a group of his Jacobin supporters went to the guillotine.

Jefferson and many other American observers who initially supported the revolution eventually turned away in disgust.

As with most of history’s revolutions, the French version simply went full circle. One tyrannical regime was replaced by another one, one in many ways more ruthless and absolutist than the last.

From the maelstrom of this anarchy and ruthless self-destruction came forth a dictator, Napoleon Bonaparte. Bonaparte restored order in France, but brought the revolution to a close after tearing a violent swath across Europe, then meeting utter defeat at the hands of the Russian winter and final defeat at Waterloo.

Then, to cap it off, the hated monarchy was restored, barely a generation after the fateful storming of the Bastille.

It’s noteworthy that the Constitution of the United States went into effect in 1789, the same year as the storming of the Bastille and launch of the French Revolution.

Since that time, the system created by our Founding Fathers delivered and even extended liberty to posterity as we forged a “more perfect union,” in the words of the preamble to the Constitution and of Abraham Lincoln.

In a republic founded mostly by slaveholders, slavery was abolished “four score and seven years” later, in large part due to our long-standing adherence to the timeless principles of the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal.”

Also, importantly, because Americans have an attachment to the rule of law and self-government, we have an attachment to ordered liberty.

The vengeful frenzy of the French Revolution produced neither liberty, nor equality, and certainly not fraternity.

Americans have generally believed in building upon the Constitution instead of burning it, even when society has seemed unjust, and it has certainly been far, far more unjust in the past than anything we see today.

On the other hand, since 1789, France has had four republics and its share of monarchs and emperors.

Which path was better: the sober—if contentious—path of the American Revolution or the bloody, lawless, and unrestrained French Revolution?

It’s not a difficult choice.

Now is the time for leaders who still believe in liberty and constitutional self-government to stand up for our institutions against those who—in some cases, literally—want to tear it down.