When U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer testified before the House Ways and Means and Senate Finance committees last month on the Trump administration’s trade policies, much of the discussion was focused on the progress of the Phase One Economic and Trade Agreement with China.

Lighthizer was able to shed some light on how his agency plans to monitor Chinese compliance.

However, using the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative’s methodology, there’s still a large gap between what China has purchased so far and what it will need to purchase in order to satisfy the deal. So, Congress is right to question that part of the deal.

Hopefully, China’s being unable to satisfy those purchases won’t undermine the achievements made in the rest of the deal. They are achievements Lighthizer has been lauding for months.

Looking at Agriculture Purchases

The Phase One deal, entered into force in February, outlines that China must buy an additional $200 billion worth of specific goods and services, on top of the value of those goods and services the U.S. exported in 2017 ($79 billion).

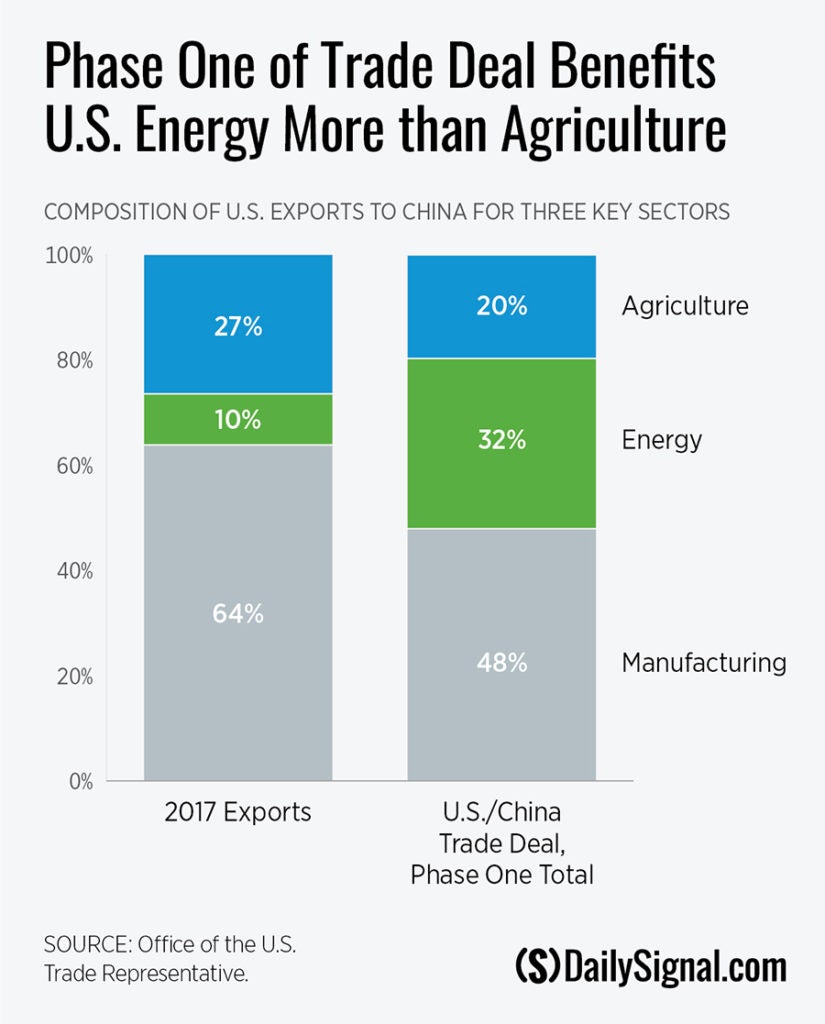

What China must purchase is spread across agricultural, manufactured, and energy goods, and it must purchase those additional goods within two years.

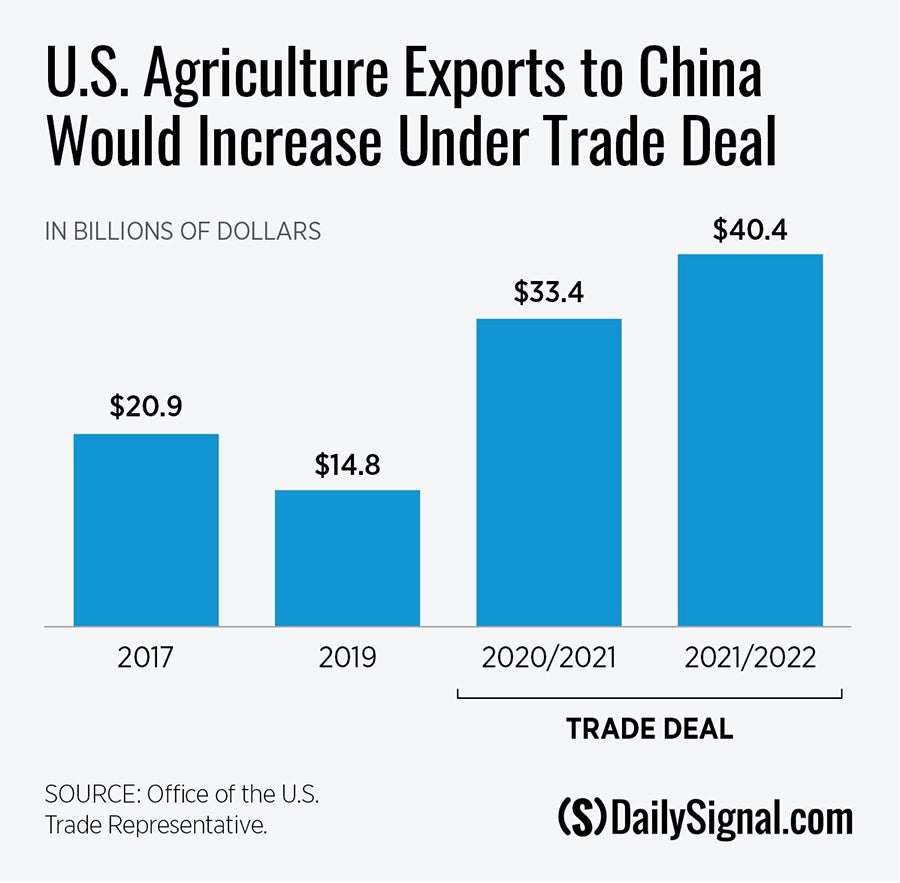

That means China must purchase $12.5 billion worth of additional agriculture goods in the first year, and $19.5 billion in the second year, on top of the $20.9 billion worth of agriculture goods exported in 2017, for a grand total of $73.8 billion worth of agricultural exports. That’s an amount far above previous heights for U.S. agriculture exports.

During the hearings, members of Congress seemed particularly interested in hearing about the future of China’s agriculture purchases. Perhaps that’s because exports of those agriculture goods have decreased almost 30% between 2017 and 2019. Soybean farmers have lost the most.

However, looking at the numbers, agriculture makes up the smallest portion of China’s additional Phase One commitments.

Differences in Accounting for Soybeans

One issue that was brought up during the hearings with Lighthizer was whether China is currently on track to fulfill its purchase commitments, since the Phase One deal has been in force for four months now.

If you look at the monthly exports of the Phase One goods so far this year, either starting at the beginning of the year or when the Phase One deal went into force in February, the value falls short of matching the 2017 level, let alone satisfying the additional $63.9 billion worth of goods required in just Year One.

Chinese buyers would effectively have to double their monthly purchases to satisfy Year One’s commitment.

Lighthizer was critical of this method, however, saying it doesn’t take into account sales that have yet to be exported and seasonality (because certain crops sell during different times of the year).

There’s some legitimacy to his criticisms. Generally speaking, the majority of soybean exports happens between September and December. And for that to happen, sales increase in July and August.

Instead, Lighthizer said, his team will be measuring China’s commitments based not just on exports, but on sales, like U.S. export sales as published by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

However, using this method to look at just soybean exports, there’s no way to tell whether China is on track to fulfill its agriculture purchase commitments right now or not.

Soybean sales can be a good proxy for all Phase One agriculture exports because they represent more than 55% of the agriculture exports to China, far exceeding any other agricultural commodity.

For as long as the Phase One deal has been in effect (mid-February to mid-June), compared with the same time period in 2017, China has exceeded the purchases it made then in both volume and value.

Using the Office of the Trade Representative’s method of taking into account the sales of soybeans, in addition to the exports of soybeans for that time period, Chinese buyers have purchased $1.24 billion worth of soybeans toward its Year One commitment.

That’s close to $1 billion more than what was purchased during the same period in 2017 ($365 million).

Chinese buyers have also ordered more than 3 million tons of soybeans at a price of more than $1 billion, but only for the next “market year,” which runs from September 2020 to September 2021.

Given that the deal has been in force for four months already, and that China will likely need to purchase $19 billion worth of soybeans in Year One, more than 90% of Year One’s exports and sales will need to happen over the next eight months.

This is just one of the problems with trying to sync up seasonal crop sales with large, government-directed purchases.

U.S. soybean farmers will have to rely on China’s large state-owned enterprises, Sinograin and COFCO, as their major customers. That will only further distort the price and demand for soybeans.

Another problem is that while there’s weekly available information on U.S. agriculture exports, there’s less readily available information on manufactured and energy goods exports—goods that also don’t get the bonus of seasonal increases at the end of the year.

Throughout the hearing, though, Lighthizer reassured members of Congress that Chinese officials had reassured him the purchases will be made.

More recently, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo tweeted that during a meeting with Chinese Politburo member Yang Jiechi, he also was reassured that China was committed to the Phase One purchases.

Certainly, the current purchases should be seen as China’s commitment to the deal. But don’t be surprised if China is still unable to fulfill the promises of those large purchases.

These are the flaws with trying to force another government to purchase an arbitrary amount of U.S. goods. And it takes away from the fact that the Phase One deal isn’t just about making purchases.

The whole point of the past three years of the U.S.-China trade war was to address China’s inability to protect American companies’ trade secrets from theft and from having to transfer technology to Chinese competitors, and to remove nontariff barriers for American exports—all which the Phase One deal includes.

Congress should rightfully question whether China can meet the purchase commitments, but it’s hardly the most important part of the Phase One deal.