According to a report this week from the Department of Justice’s inspector general, the FBI failed to be “scrupulously accurate” with information presented to a secret federal court to seek national security-related warrants pursuant to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act.

But a closer read of the report on the FBI’s relationship with the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act Court and what we already knew reveals that to be a dramatic understatement.

This latest report on FISA-related issues is a follow-on to the troubling trend of abuses the inspector general first detailed in a report late last year. Details from the earlier report are now familiar.

Essentially, the FBI relied on dubious evidence to place Trump campaign advisor Carter Page under surveillance. More importantly, in the process of obtaining permission from the FISA court to take certain actions, the FBI committed at least 17 flagrant errors, omissions, and misstatements across four FISA applications, the first report revealed.

“That so many basic and fundamental errors were made by three separate, hand-picked teams on one of the most sensitive FBI investigations that was briefed to the highest levels within the FBI … raise[s] significant questions regarding the FBI chain of command’s management and supervision of the FISA process,” the previous report stated.

This latest report provides some initial answers to those questions. And they’re not good.

To understand the inspector general’s findings, go back about 20 years to 2001. Then, as now, numerous factual errors were found in FBI FISA-related applications.

To limit and combat these systemic errors, FBI attorney Michael Woods implemented a series of procedures to ensure that information on a FISA application was “scrupulously accurate.”

This high bar is appropriate given that FISA is such a powerful surveillance tool and the potential for its abuse.

As part of those procedures, FBI agents have to compile and maintain a “Woods File” that contains supporting documentation for every factual assertion presented in a FISA application. The case agent then signs a form attesting that each factual assertion is accurate and that supporting documentation is in the Woods File.

The agent’s supervisor then must review the file and also sign the form attesting that such documentation exists in the file. Only then can the FISA application be submitted to the court.

Based on the inspector general’s findings, this hasn’t been happening. Not even close. His staff reviewed 29 FISA applications submitted from eight different FBI field offices over the past five years.

Every application had issues.

For four of the 29, the FBI couldn’t find a Woods File. For three of those four, FBI officials didn’t even know whether Woods Files had ever existed. For the files that were reviewed, the inspector general said:

… for all 25 FISA applications with Woods Files that we have reviewed to date, we identified facts stated in the FISA application that were: (a) not supported by any documentation in the Woods File, (b) not clearly corroborated by the supporting documentation in the Woods File, or (c) inconsistent with the supporting documentation in the Woods File.

That all boils down to “an average of about 20 issues per application reviewed, with a high of approximately 65 issues in one application and less than 5 issues in another application.”

Equally troubling, the report highlighted issues with the current review processes within both the FBI’s Office of General Counsel and the Justice Department’s National Security Division. Each entity is supposed to conduct annual reviews of selected FISA applications to ensure their accuracy.

But those reviews don’t focus on the accuracy or completeness of Woods Files, and they provide notice of which applications they will review, which gives agents time to compile supporting documentation for those FISA applications—even though such documentation should exist already in the Woods File.

Even with this advance notice, errors abound.

The inspector general found that in 34 FBI and National Security Division accuracy review reports, covering 42 FISA applications, “390 issues, including unverified, inaccurate, or inadequately supported facts, as well as typographical errors” were found.

None of the 390 issues were deemed material by either the FBI or the National Security Division, but neither the FBI nor the National Security Division reviewed the errors to determine if they were material.

Moreover, the report says “the FBI requires its Chief Division Counsel in each FBI field office to perform each year an accuracy review of at least one FISA application from that field office,” which are forwarded to FBI headquarters.

But these reports are catalogued in a standardized report “only to ensure CDC compliance with the requirement to perform the reviews” and not toward helping the FBI determine whether its agents were complying with Woods Procedures on FISA applications.

So, what’s to be done?

The FBI has adopted and is implementing the reforms suggested by the inspector general in his earlier report.

And FBI leadership has indicated a willingness to accept additional reforms recommended by the inspector general, including (1) to systematically and regularly examine the results of accuracy reviews to enhance training and to ensure the accuracy of FISA applications and (2) to ensure that Woods Files exist for all FISA applications in pending investigations. Good and reasonable first steps.

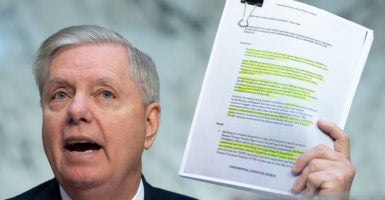

Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Lindsey Graham also intends to call the inspector general before his committee to discuss the report.

Clearly, additional safeguards need to be implemented, especially since the FBI implemented the Woods File procedures to remedy earlier problems with FISA applications. Increased congressional oversight is a good place to start.

Unfortunately, this report may be only the beginning of what could be a tsunami of bad news. If errors in Woods Files were found to be material, that could create even bigger problems because they could have influenced the court’s decision whether to grant certain FISA applications.

At best, the FBI acted sloppily. At worst, it acted with a stunning degree of malfeasance. At a minimum, it violated the public’s trust and damaged the public’s perception of the integrity of our national security apparatus, perhaps irrevocably. Attorney General William Barr and FBI Director Christopher Wray clearly have their work cut out for them.

And there may be other shoes to drop.

The new report states that in connection with its ongoing audit, the inspector general’s office “will conduct further analysis of the deficiencies identified in our work to date and of FBI FISA renewals,” and will be “expanding the audit’s objective to also include FISA application accuracy efforts performed within NSD.”

As a result of all this, the FBI may well have undermined the intelligence community’s ability to use some FISA-related tools in the future. A tough debate has been raging in Congress about the propriety of reauthorizing certain controversial FISA provisions.

By failing to be “scrupulously accurate” with the information provided to the FISA court, the FBI has given ammunition to FISA’s opponents, potentially damaging our ability to conduct thorough investigations against foreign governments and terrorists who mean us harm.