“The biggest problem plaguing U.S. public schools [is] a lack of resources.”

So claims Robert Pianta, dean of the University of Virginia’s Curry School of Education, in an op-ed published last week in The Washington Post. In fact, Pianta asserts, government spending on K-12 education actually has declined since the 1980s.

These claims are inaccurate, as federal government data prove.

In fact, it is so clear that government spending on K-12 education has increased dramatically—after adjusting for inflation—that The Washington Post just issued a correction to Pianta’s article:

Correction: An earlier version of this piece stated that, adjusting for constant dollars, public funding for schools had decreased since the late 1980s. This is not the case. In fact, funding at the federal, state and local levels has increased between the 1980s and 2019.

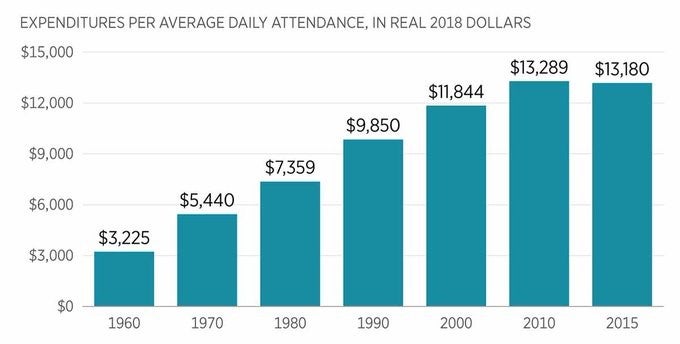

The Post was wise to issue the correction. In real dollars, total government spending per pupil increased from $7,359 in 1980 to $9,850 by 1990, reaching $13,180 per pupil by 2015.

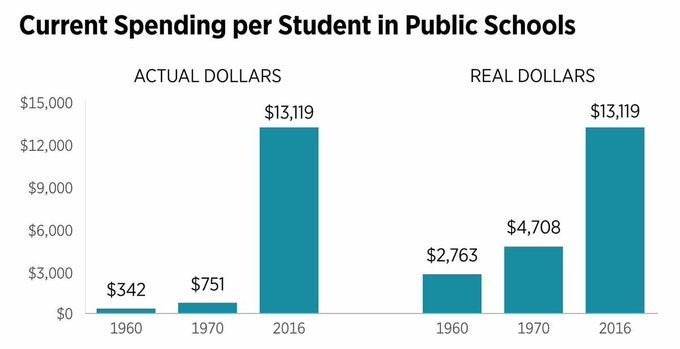

Taking a longer view, real spending per student in public schools has increased from $2,763 in 1960 to more than $13,000 today.

Considerable evidence shows that government spending has little if any relationship to academic achievement. Inflation-adjusted spending has quadrupled since 1960, four years before President Lyndon Johnson launched his Great Society education programs designed to wage a War on Poverty and narrow opportunity gaps between affluent and poor children.

As Stanford economist Eric Hanushek explains, despite this fourfold increase in government spending, student outcomes remained flat:

This productivity decline is remarkable, particularly when compared with dynamic improvements in productivity elsewhere in the U.S. economy. Schooling outcomes are the same in 2015 as they were four decades before, even though school funding is now several times as high.

Notably, as both Hanushek and Harvard’s Paul Peterson have documented, the gap in learning between students from the top 10% and bottom 10% of family income was the equivalent of four years’ worth of learning prior to the launch of the Great Society. Today, it stands unchanged—at four years’ worth of learning.

>>> Related: The Not-So-Great Society

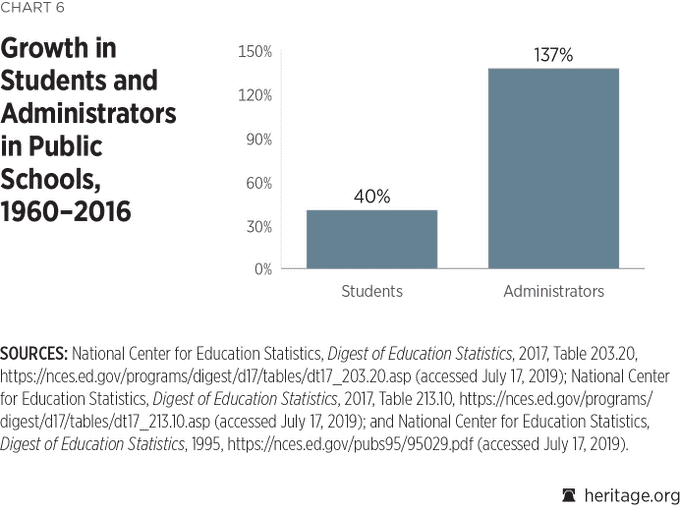

It is possible that Pianta was basing his assertion that school spending has declined on what he hears from teachers, who may not feel the increases in spending. As EdChoice’s Mike McShane and Jason Bedrick have documented, most of that spending has been captured by the schooling bureaucracy.

This nice chart originating from Kennesaw State University’s Ben Scafidi puts a finer point on it:

But no matter how you slice the data, contra Pianta, spending is in fact up. It is the one thing that has been tried ad nauseam. What hasn’t been tried is changing not what is spent, but who controls the dollars that are spent.

Giving families, rather than government officials, control over education funding is what will make a difference long term—a fact the data clearly support. Education choice improves academic achievement, attainment, safety, satisfaction, and a host of other important outcomes in later life.

So let’s set the record straight on education spending, and what really matters for students across the country.