Responding to popular anxiety over prescription drug prices, the Senate Finance Committee last month approved a bill to restructure the Medicare prescription drug benefit.

The bill is part of broader congressional and administration efforts to address rising health care costs, one in which lawmakers are laying aside partisan differences to seek constructive solutions.

The committee is proposing amendments to the Medicare Part D program, which was created in 2003 and requires modifications to address the changing nature of the prescription drug marketplace.

The Prescription Drug Pricing Reduction Act contains a mix of good and bad ideas for amending the program, which relies on choice and competition to provide prescription drug coverage to 47 million seniors. Medicare Part D is widely popular with beneficiaries and has cost taxpayers far less than initially estimated.

The bill’s good ideas include reworking how the program pays for the costliest drugs, relieving taxpayers of some of these costs, and requiring private prescription drug plans and pharmaceutical companies to assume a greater burden.

The worst idea is one that would introduce federal price regulation into the Medicare Part D program. More on that in a bit. First a look at how the bill proposes to restructure Medicare Part D benefits.

Restructuring Medicare Part D

Under Medicare Part D, prices are set through negotiations between private pharmacy benefit managers and drug manufacturers without government involvement.

Competing prescription drug plans sponsor insurance policies that cover drugs and set their premiums. The government subsidizes these premiums at fixed rates.

Prescription drug plans compete for seniors’ business based on quality and price. Seniors can choose the plan that provides them the best value, covering the medicines they take at the most affordable prices.

Consumer choice and competition have made Part D the rarest of government programs: one in which spending hasn’t spiraled out of control. In fact, government actuaries report that federal general revenue spending on the program was $67.8 billion in 2018—that’s less than what it spent in 2015 ($68.4 billion).

Over that same period, government spending on Medicare Part A (hospital inpatient benefits) increased by 10.5% (from $279 billion to $308 billion), while general revenue spending on Part B (physician and other outpatient benefits) grew by 24.2% (from $203.9 billion to $253.2 billion).

The Part D program has also resulted in reduced spending elsewhere in the Medicare program by making drug therapies broadly accessible to seniors. These therapies help keep beneficiaries out of hospital beds and emergency rooms, reducing Medicare spending on hospitals and doctors.

A December 2016 study by economist Robert J. Shapiro found that the Part D program had produced net Medicare savings of $679.3 billion between 2006 and 2014.

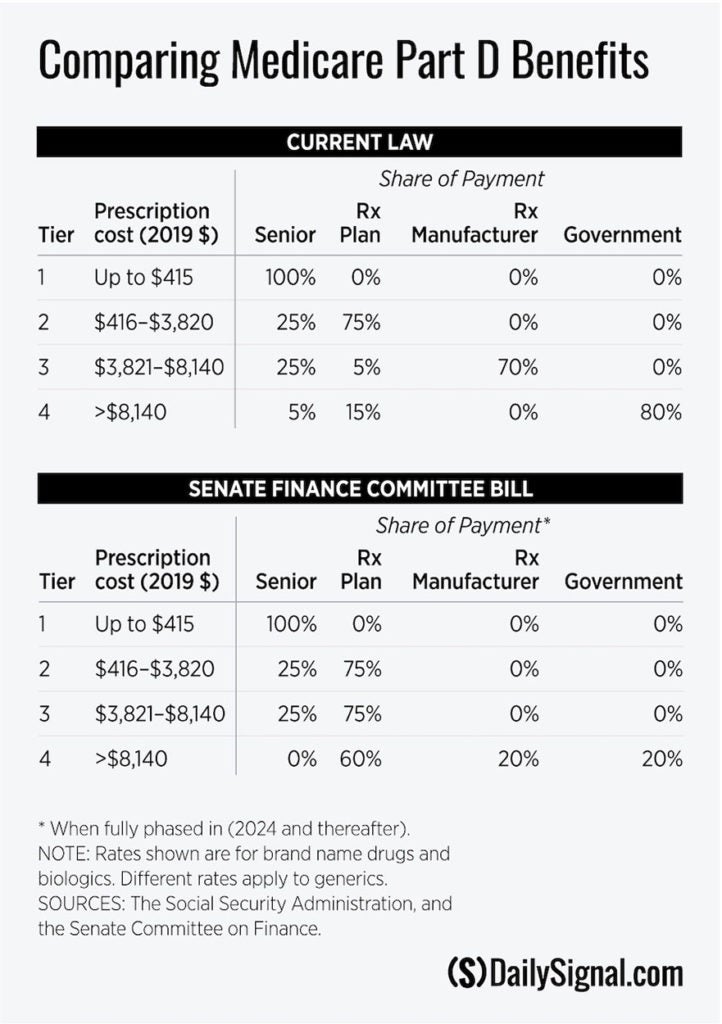

The Part D program has achieved these results through competition among prescription drug plans and through a standard drug benefit that apportions costs among beneficiaries, plans, manufacturers, and the government. The benefit consists of four tiers (see the table).

In the first tier, the beneficiary pays the full cost of prescriptions up to the $415 deductible. In the second tier ($416-$3,820), the beneficiary share drops to 25%, with the plan picking up the remaining 75%. In the third tier ($3,821-$8,140), the beneficiary share remains at 25%, but the plan’s share plummets to just 5%.

The remaining 70% falls on the manufacturer, who must help finance the program by discounting prices on brand name products. Beneficiaries who enter the fourth (catastrophic) tier (spending above $8140) pay 5% of the cost. The plan picks up 15%, with the government bearing the remaining 80% of the bill.

It is thus in the interest of both plans and manufacturers to have a beneficiary’s spending jump to the catastrophic tier, where they bear little or none of the costs.

The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), an advisory arm of Congress, has noted that spending in the catastrophic tier grew from 25% of Part D costs in 2007 to 54% in 2017, even as overall spending on the program grew only modestly. MedPAC has urged Congress to restructure the Part D benefit to better align financial incentives in the catastrophic tier.

The Finance Committee bill proposes such a restructuring. The measure, as the table shows, would reduce the government’s share in the catastrophic tier to 20%, with the remaining 80% of the costs divided between plans (60%) and manufacturers (20%).

That would provide powerful motivation for plans and manufacturers to seek ways to better manage costs in Part D’s fastest-growing component. It thus would reinforce Part D’s reliance on market forces to control spending.

According to a preliminary analysis by the Congressional Budget Office, this restructuring of the Medicare benefit would save taxpayers $34.6 billion over 10 years.

This aspect of the Finance Committee’s proposal is notionally sound. It seeks to better align incentives among private entities.

Key details remain open, and those details will greatly affect whether this promising reform will actually work. A more detailed analysis is needed to determine the provision’s effect on premiums and whether costs in the catastrophic tier are appropriately allocated.

As critical as these details are in evaluating this provision’s merit, the basic concept and approach is right. These improvements to the Part D program would rely on market forces, rather than on government intervention, to moderate prescription drug prices.

How Intervening in Drug Pricing Could Backfire

While these changes are promising, the bill also contains a provision that veers sharply away from Part D’s market-based approach. Instead, it would require drug manufacturers to pay rebates to the federal government on any list price increases on their brand name products that exceed the general rate of inflation.

The bill directs the secretary of health and human services to collect this penalty and deposit the proceeds into the Medicare trust fund.

Some argue that these rebates do not constitute government price regulation, but should instead be understood as an appropriate reduction in government subsidies to drug companies. They are mistaken for three reasons.

First, and most obviously, the government pays no subsidies to drug companies under Medicare Part D. It pays premium subsidies to private prescription drug plans, which negotiate rebates and other price concessions from manufacturers and compete to enroll seniors.

Since the government pays no subsidies to drug companies, there is no subsidy to reduce.

Second, the inflation penalty that the government would impose on drug-makers would be based on list prices.

Part D plans do not pay list prices for drugs. Rather, they negotiate substantial price reductions with manufacturers. These rebates and other price concessions are considerable, amounting to 27.3% of total Part D drug costs in 2019.

Pharmacy benefit managers base their premiums on these net prices, not on list prices. Likewise, government premium subsidies paid to Part D plans are based on net prices, not list prices. There is no rationale for assessing Medicare Part D penalties on manufacturers based on prices that Medicare Part D plans do not pay them.

Third, government spending on the Part D program has been stable, despite increases in list prices. This suggests that list prices aren’t well correlated with government spending on the program and that penalizing manufacturers for list price increases is poorly conceived.

Finally, the proposed penalty on drug-makers would build on failure by adding a long list of market-distorting price regulation that the government already imposes on pharmaceuticals. These include government-mandated rebates paid by manufacturers to states and the federal government under Medicaid, similar price regulation under the 340B program, and VA price controls.

The effects of each of these requirements would ricochet through the economy, introducing distortions and contributing to higher drug prices.

Imposing Medicare penalties on drug companies that raise their list prices is fundamentally at odds with the Part D program’s reliance on private entities to negotiate discounts on behalf of seniors.

So, why is anyone considering this bad policy idea at all?

It may represent an attempt to straddle political differences between Republicans, who generally favor Part D’s market-based approach to drug prices, and Democrats, many of whom want Part D prices set through direct “negotiations” between the government and drug-makers.

The Finance Committee bill seeks to split the partisan difference by establishing a two-tiered system. Drug prices in the Part D program would continue to be set without government interference, even as the secretary of health and human services separately exacts penalties against drug companies that increase their list prices.

It’s an awkward fit—combining privately negotiated net prices with government-regulated list prices—and one that may yet flop politically.

Some Senate Democrats are unhappy with the bill because it does not direct the secretary of health and human services to “negotiate” drug prices with pharmaceutical companies. House Democrats have yet to release their version of the measure, but there is strong sentiment within their caucus to include such a provision.

Meanwhile, all but two Finance Committee Republicans voted to strip the penalties from the bill. The amendment failed on a 14-14 tie. Once that amendment fell, most Republicans voted against the bill.

The panel approved the measure largely because all committee Democrats voted for it. That clouds prospects for the bill’s passage.

Overall, this bill includes some very good ideas—but its future should depend on the willingness of leaders to strip it of a very bad one.