Without a doubt, Bill Buckley would have happily joined the recent National Review Caribbean cruise, which sailed from Key West to the Dominican Republic to the Bahamas to Fort Lauderdale on the good ship Oosterdam of the venerable Holland America Line.

He would have been surrounded by the perspicacious editors and contributors of his favorite magazine—including the soft-spoken Jay Nordlinger and master impresario Jack Fowler, and some 250 of the golden donors who enable National Review to keep publishing—after 63 years—and making a constitutive difference in the politics and culture of America.

Buckley would have relished the discussion of such consequential issues as immigration, the Second Amendment, abortion, identity politics, the evangelical right, the secular left, and, inevitably, the presidency of Donald Trump, who delights in doing things his own tweet way.

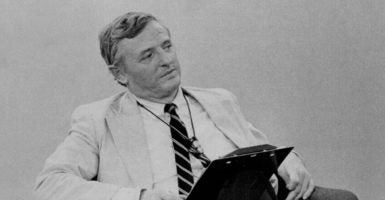

With pen in hand, clipboard on lap, and eyebrows at the ready, Buckley would have questioned pollster Scott Rasmussen, who said of the 2018 elections that “neither political party resonates with the American people” and that for a majority of women, “conservative” is as negative a word as “liberal.” Republicans need to be more pragmatic, he said, to be seen as problem solvers.

On the immigration panel, author Nick Adams caught the attention of the audience when he said, “Immigration without assimilation is invasion.” He added that “e pluribus unum [one out of many] has always been a key in America,” but that oneness depends on one, not multiple cultures. In a later panel, Adams averred that “the left has waged a culture war in America for the last 60 years … we must fight back.” Immigration guru Mark Krikorian questioned whether it was too late, given that our K-12 schools teach that “America sucks.”

Conservative luminary Jonah Goldberg declared, “We are at a moment of great transition and change.” Mediating institutions, he said, are fading. We are not civilizing society properly. Echoing Alexis de Tocqueville (and Edmund Burke), he said that “we must build up [our] local institutions.” Regarding the future of conservatism, Goldberg admitted, “I may have to walk away from the word ‘conservative,’” drawing gasps from listeners.

Properly, for a National Review cruise, there were speakers who accentuated the positive. Movie-TV producer Rob Long urged conservatives in their cultural enterprises to concentrate on telling a story, not making an argument. He praised the Broadway musical “Hamilton” for accepting that the Founders were great men and declared it deserving of a congressional medal.

Looking ahead to the 2020 elections, all the panelists, from New York Post critic James Lileks to National Review writer Alexandra DeSanctis, doubted there would be a Republican challenge to Trump in 2020. Rasmussen again raised the viability of the conservative “brand.” The problem, he said, is that Buckley was successful in selling one brand of conservatism—pro-capitalism, anti-communist, faith-based—but “nobody has any idea what conservatism is today.”

Ever the optimist, I politely disagreed, and during my presentations made the following points.

Bill Buckley was a master fusionist—editorially, politically, socially. Conservatives should emulate his philosophy of adding, not subtracting, multiplying, not dividing the several strains of conservatism.

Buckley was a conservative without apology, but counseled support for the conservative who has the best chance of winning, not the simon-pure candidate who proudly marches over the cliff with flags flying and the band playing.

Buckley would welcome modern populists into the conservative coalition, knowing that populism and conservatism have a long history starting with the “Draft Goldwater” movement in 1964; continuing with Ronald Reagan, who won a 1980 landslide with the help of the Moral Majority; and extending to the tea party that rocketed into existence in 2009 and provided the winning margin for Trump in 2016.

(Side note: In 1965, Buckley won the votes of working-class Irish Democrats—early-day populists—when he ran for mayor of New York City.)

I stressed that Buckley delineated the critical difference between the conservative movement and the Republican Party, which are two separate institutions. The latter is a political party interested in winning races and gaining power. Conservatism is an intellectual movement dedicated to ideas that often have political application. The fortunes of the conservative moment are not automatically tied to the inevitable ups and downs of the GOP.

I concluded by pointing out that in his leadership of the conservative movement, Buckley sided with T.S. Eliot, who wrote that there are no lost causes because there are no gained causes. Indeed, Buckley welcomed the never-ending struggle to preserve and protect the priceless idea of ordered liberty.

That cause wasn’t lost in Buckley’s day, and it still isn’t lost today.