President Donald Trump announced his nomination of D.C. Circuit Judge Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court on July 9 at 9 p.m. Before the clock had struck midnight, Democratic senators were already announcing their opposition.

Now, more than eight weeks later, they are just playing games.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., for example, said on July 9 that he was voting “no” because of “Judge Kavanaugh’s record and writing, which I have reviewed.” Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., similarly said that night that he was “strongly opposed because … Kavanaugh has an immensely troubling record.”

Other Judiciary Committee Democrats had already beaten them to the opposition punch. Nearly two weeks before anyone knew the nominee’s name, Sens. Kamala Harris, D-Calif., and Mazie Hirono, D-Hawaii, had announced they would be in the negative column.

The confirmation process—the one-on-one meetings, questionnaires, background investigations, reams of documents about the nominee’s legal career, hearings, and debates—had not yet occurred. None of those things mattered to these senators, because they already had their minds made up.

Each senator can obviously decide how (or even whether) to participate in the confirmation process for the president’s nominees.

They can be thoughtful and deliberative, rash and reckless, foolish and irresponsible, thorough and careful, or even downright underhanded and dishonest. But when senators say they know enough about a nominee to have decided how to vote, you can question their motive for later acting like the process actually matters after all.

Judiciary Committee Democrats first demanded that the hearing be delayed so they could review more documents about a nominee they already opposed.

Never mind that the committee had, as of two weeks before the hearing, posted more than 267,000 pages of documents—more than for any previous Supreme Court nominee—to its website.

Never mind that the time between Kavanaugh’s nomination and hearing was 25 percent longer than the average for nominees over the previous three decades.

Now that the hearing is over, the committee’s practice is to consider the nominee in a business meeting after he has answered post-hearing written questions.

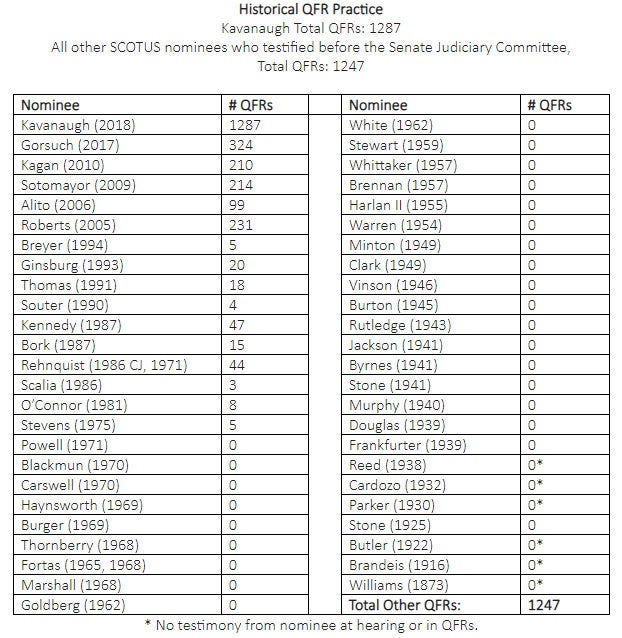

Democrats are at it again, submitting 1,278 questions to Kavanaugh. That’s three times as many as for both of President Barack Obama’s Supreme Court nominees, Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor; 51 times as many as for both Stephen Breyer and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, nominated by President Bill Clinton; and 86 times as many as for Robert Bork, whose nomination was actually defeated by the Senate.

In fact, that is more than the total for all previous Supreme Court nominees combined.

Blumenthal, who said on July 9 that he had reviewed Kavanaugh’s record and was ready to vote “no,” submitted 100 questions. Hirono, who announced her opposition nearly 80 days ago, gave Kavanaugh 122 questions. Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., who is up for re-election this year, grabbed the top spot with 241 written questions.

In his hearing, Kavanaugh repeatedly explained that he would not offer “hints, forecasts, or previews” about issues that could come before him on the Supreme Court. That included a “thumbs up” or a “thumbs down” about Supreme Court precedents.

Among the 161 questions submitted by Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., dozens ask for the very views that he knows Kavanaugh cannot provide, such as how specific Supreme Court precedents apply in hypothetical situations.

Dozens of other questions ask about matters related to Kavanaugh’s opinions on the U.S. Court of Appeals that anyone reading those opinions would know already: Which party prevailed? What was the “substantive ground” for the decision?

Then there were questions that not only would be virtually impossible to answer, but had no possible relevance to Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination. Whitehouse asked, for example, about all participants in any “game of chance or skill” over the past 18 years. Yes, that really was one of the questions.

Or how about this: “Have you ever sought treatment for a gambling addiction?” This is loathsome treatment from a senator who long ago said he would oppose Kavanaugh anyway.

Senate Democrats once posited that a Supreme Court nominee’s past judicial record is the best information to review in order to evaluate him or her. Today, Democrats will talk about anything but Kavanaugh’s judicial record. They will talk about just about anyone but Kavanaugh himself.

One thing they will not do is explain their real reason for opposing Kavanaugh. That is that he will be an impartial—rather than a political—judge. He will not be driven by a political agenda, he will not decide cases to ensure that certain parties win.

All the misdirection, the fake indignation, the sudden interest in a once-irrelevant confirmation process, or the most creative obstruction tactics cannot hide the political truth.

Liberals want one thing from the courts—namely, what President John F. Kennedy’s appointee Byron White once called “raw judicial power.” They oppose Kavanaugh because he won’t give it to them.